In her vérité-style documentary, The Brink, Washington Square Films filmmaker Alison Klayman took an unexpected approach to confronting political extremism, embedding herself directly in the belly of the beast.

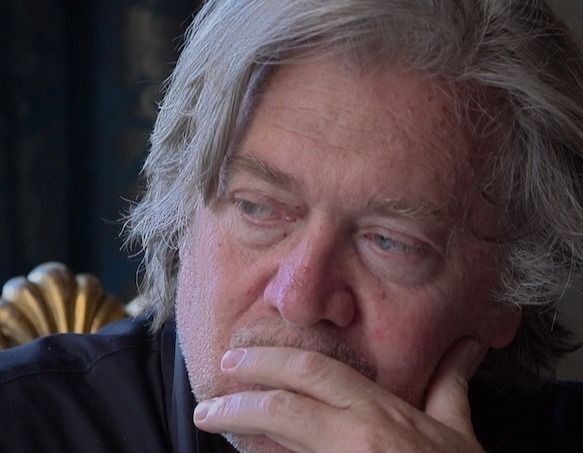

Following notorious former Trump administration Chief Strategist Steve Bannon during the year after his ousting from the White House, Alison went into the experience of filming looking to demystify, rather than humanizing the Breitbart founder. Sticking close to Bannon as he travels through Europe, hoping to mobilize and unify far-right parties in order to win seats in the May 2019 European Parliamentary elections, Alison takes on Bannon’s hypocrisies and contradictions, maintaining a careful balance between fly on the wall filmmaking and voicing her own personal perspective in crucial moments.

The result is a film that engages critically with Bannon’s presence, deconstructing media mythology surrounding him to more accurately confront him in reality.

The Brink premiered at Sundance 2019 and is set to be released by Magnolia Pictures on March 29th—don’t miss it in theaters.

We spoke with Alison about pushing the boundaries of what’s been accomplished in documentary filmmaking, shooting as a bare bones crew of one, and the challenge of letting Bannon underestimate her while never underestimating him.

The Brink is a close look at intensely controversial right-wing political figure Steve Bannon. How did the opportunity to shoot this film come about?

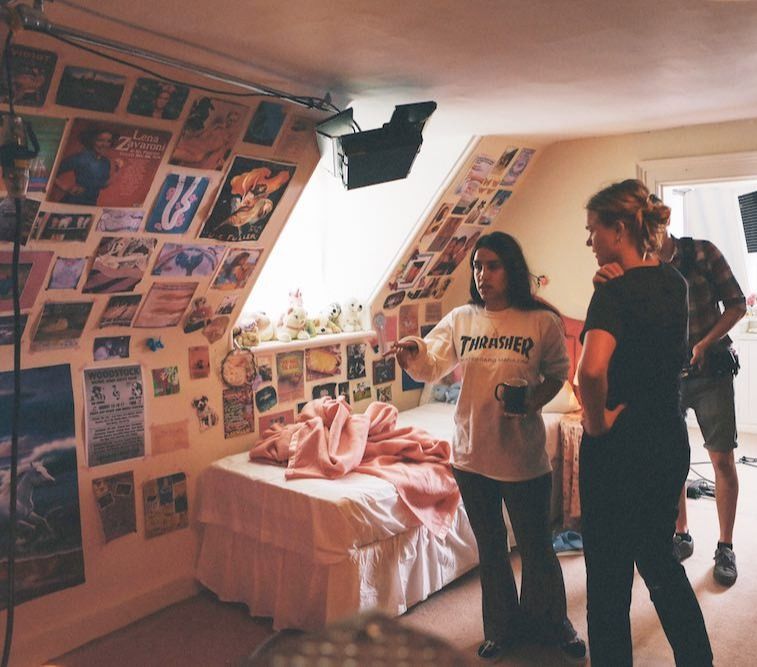

Alison Klayman: This backstory of this film is really about two women taking on a very powerful man with politics they abhor. My producer Marie Therese Guirgis worked for Bannon at an arthouse film distribution company called Wellspring Media in the early 2000s. This was before he adopted such extreme right-wing politics. After he joined the Trump campaign, she reconnected with him to express her displeasure and disappointment (aka sending him hate mail), and to her surprise, he would response to her messages. She realized there might be a bigger opportunity at hand, and eventually asked him to make a vérité documentary following him, in which he would have zero creative control. He said no a few times, and then said yes.

She always had me in mind to direct because she thought I was the right filmmaker for the job, that I could make something smart and sophisticated, artful and exciting, and that I could insinuate myself into his world in a way that he would let his guard down. My daily mantra was: Let him be underestimating me, and let me never underestimate him.

What were you interested in investigating, going into the experience? What intrigued you about this project, within the scope of your body of work in general?

The nature of evil, and the nature of people who are behind policies that damage our country, like the Muslim travel ban, are ideal subjects to explore through documentary film, specifically vérité. Media portrayals of Bannon as a mastermind or the grim reaper were not compelling to me. I wanted to engage critically with him beyond those surface images.

I thought it would play to my strengths for vérité filmmaking—being embedded for a year, being observational, not knowing what I would encounter. It was a new challenge for me to be filming someone at the height of his political power, who I was totally opposed to politically—and he knew it. There aren’t many examples in documentary where a person like me was granted access to a person like him, and I felt it would be boundary pushing for the entire genre of documentary.

"You want your enemy to be a monster, but in truth, they’re human—for me, that’s what makes them scarier."

How did you establish a level of intimacy with your subject, required in order to capture the footage you were looking for? How do you, as a documentarian, balance your own beliefs and opinions while remaining a neutral enough presence to witness the necessary depth of your subject matter?

Bottom line is: I am a professional and this is what I do. I thought of it as lying in wait, getting him to feel comfortable and to reveal himself through his words and actions in front of my camera. Everything was in service of the film. I got outraged a lot, but I understood that I wasn’t there to intercede or fight back. I often filmed him talking to people who completely agree with him, which was surreal for me.

The point was not to humanize him, but to demystify him. Humanizing him was not the framework I employed for this project—he’s obviously a human being, he’s hungry, he gets angry. You want your enemy to be a monster, but in truth, they’re human—for me, that’s what makes them scarier.

Even though you take a cinéma vérité/fly on the wall style in this film, your own voice appears in this documentary. Were there any documentary predecessors who influenced your approach here? What was your thought process behind how you handled your own appearance on film?

I always have a little bit of my voice in my films, usually because there’s a moment with my subject that can’t play out without hearing my question. In truth, it’s something I love. I don’t make personal documentaries that I narrate or where I am a character in the story, but I think you can always feel me in my films. I think it’s nice to give a signal to the viewer that I am there: a human being (a woman) was behind the camera and is shaping this narrative. In this film, I speak up more than usual, and that’s probably because I wanted to draw attention to the filmmaker to be clear that this is my film, not Bannon’s.

"My daily mantra was, 'Let him be underestimating me, and let me never underestimate him.'"

You’ve made several documentary features, including Ai Wei Wei: Never Sorry and Take Your Pills. Can you tell us about your decision-making process when putting together your crews for these projects? What choices about crew size are you making when approaching these films?

Some of my biggest projects, Never Sorry and The Brink, are about intimate access, and were best served by having me as a one person crew. I was alone in the field, serving as the DP and recording my own sound. On The Brink, it was also a logistical benefit, because Bannon’s organization was very haphazard and his schedule was constantly set at the last minute, making it impossible to plan for a crew. It was easier to rely on being able to squeeze myself in the back of a car or grab an extra seat on a plane. On Take Your Pills, I knew we’d be doing a lot of sit-down interviews and stylized shooting, mixed in with the intimate shooting with our characters, so I wanted a crew that could operate with a small footprint. We went with a director, DP, AC, sound recordist, producer, and a PA. For doc series episodes I’ve directed, or even doc-style branded content, that’s usually the most bare-bones unit you’re likely to find.

What surprised you most during the process of shooting?

I was constantly surprised by Bannon’s flagrant hypocrisies, and also his personality contradictions. He sometimes seemed like he was very self-aware, and then other times he would do things that showed a total lack of self-awareness.

Did The Brink push your skills as a filmmaker in any new or interesting ways?

I think as a storyteller, handling this material and subject was the biggest challenge. You can’t tell the story of a hatemonger who admits he’s trying to use the mainstream media to his advantage the same way you tell just any story. How to expose the tactics, lies, and hypocrisies without any narrator or talking heads to contextualize required a sophisticated approach. I used humor, repetition, juxtaposition, and other devices to get my point across. Also, I think I am a better shooter than ever before. From working with DPs, especially on commercial shoots, I think I learned a lot, and it was rewarding to be able to achieve what I wanted with my own cinematography (and only available light!).

What elements of the final film are you most proud of?

Honestly . . . everything. I’m proud that I can see the million choices I made as a director (executed along with my brilliant creative team) and they add up to a complex and thrilling film.

In addition to your work as a documentarian, you’re also a commercial director. How does your work on documentary feature films like The Brink, influence the way that you approach commercial projects?

I think documentary feature work makes you battle-tested. Especially this film—I couldn’t imagine a more challenging project, from logistics to subject matter to storytelling to timeline. I’ve already directed a few commercial jobs since The Brink wrapped and I can feel my confidence and ability to handle challenges is higher than ever.

What kinds of commercial storytelling do you hope to have the opportunity to undertake in future?

My films all shine because I understand story, humor and how to render authentic characters, so I’d like to have more opportunity to do the same work in scripted projects.

What are your hopes for women directors, in a general sense, in the next year?

More opportunity, success and recognition. And to be making work that pushes the world away from hate.