All photos courtesy of © Lucasfilm LTD & ™. The Mandalorian is now streaming on Disney+.

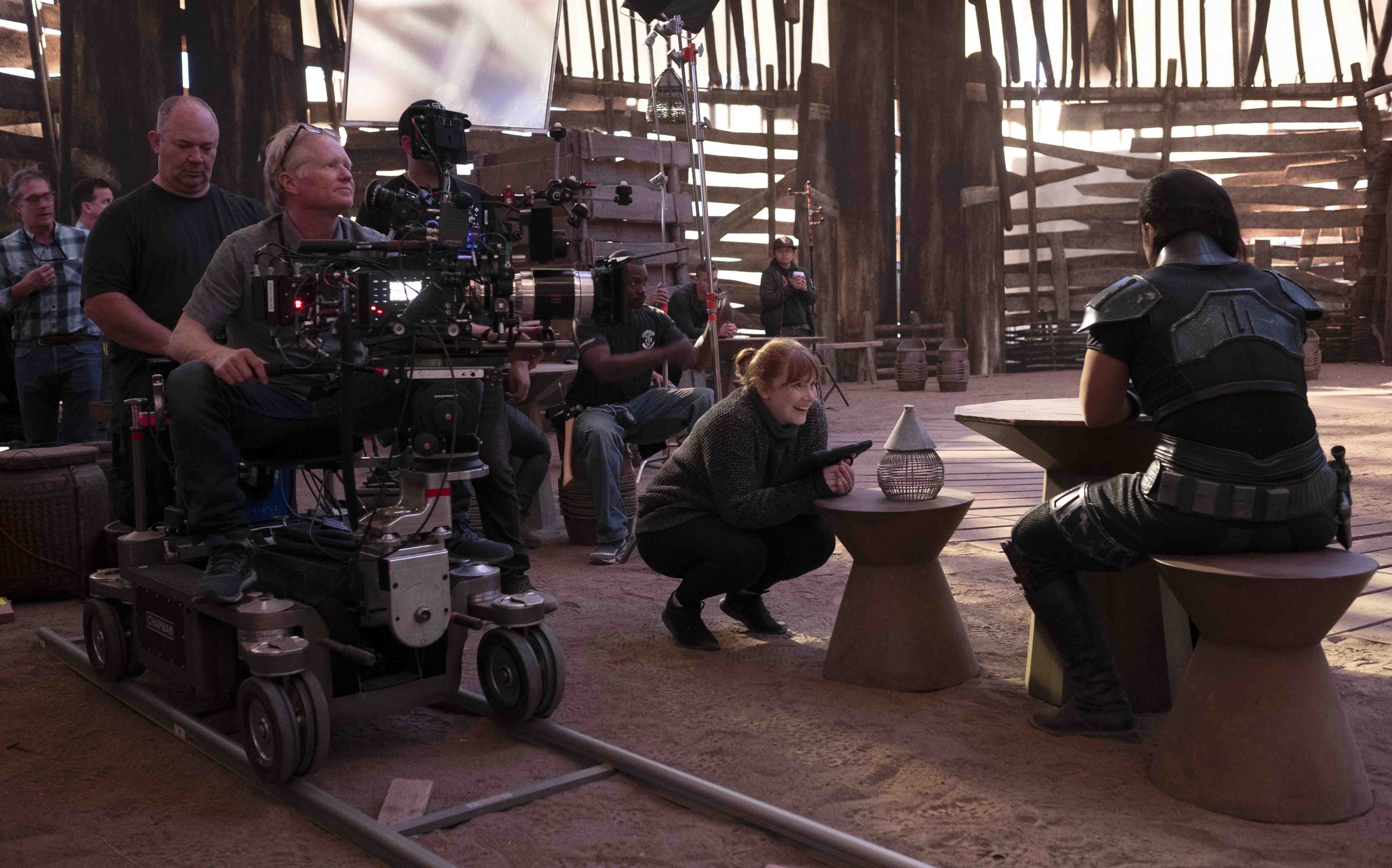

Directing The Mandalorian is basically a masterclass in fundamental and future filmmaking. Just ask director-actress Bryce Dallas Howard, who's opening up about the inventive and fearless process of shooting the new addition to the Star Wars universe.

But before she gets into it, there are a few things crucial to know, unless you want to get lost in a galaxy far, far away.

The workflow of The Mandalorian was shaped in accordance with the groundbreaking and innovative technology created by ILM, Lucasfilm’s VFX and Animation studio, which is changing the future of filmmaking forever. The Mandalorian is the first production ever to use real-time rendering and video wall in camera, creating the Volume, a 20-foot tall, 270-degree curved LED video wall that projects the environment to every planet seen on screen. The necessity for this invention came out of the constraints of staying in one location, a shortened time frame, and certain budget level, while still elevating the overall look of the show.

Because of this technology, everything needed to be planned way in advance using previs, or previsualization, which is the visualizing of complicated scenes before production. It is usually implemented on a couple of scenes that require lots of action or visual effects. On The Mandalorian, it was used on the whole episode for every episode of the season, forcing filmmakers to commit and fail early on in the process before anything has been permanently captured on film and hitting the stage to film in the Volume.

Got all that? Great. That's just beginning. Now we're ready to go behind-the-scenes with Bryce.

FTW: First off, how do you get past the nerves of taking on a Star Wars project?

Bryce Dallas Howard: In my acting career, I’ve had a lot of great opportunities to see how directors deal with IP that has extraordinary meaning to multiple generations of audiences. When I sat down with Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni and heard them talk about Star Wars, it really clicked. The intimidation factor goes down when you realize that your bosses are baller and that you’re being protected by them.

I have a theory that helps me, which is that the best working experiences are when you’re working for people that you would actually hire yourself. Oftentimes we feel so lucky to just get the job and that is the truth. But sometimes you get even luckier because the person who’s giving you the job is someone that you would raise your hand to work with in any way, shape or form. That’s what I experienced on The Mandalorian. It’s a magnificent collaborative spirit and fear doesn’t play a role in the work at all.

How do you achieve a single, united Mandalorian vision with multiple directors in a season?

The workflow that Jon cemented for The Mandalorian is pretty extraordinary. It allows all of the directors to get on the same page very early as to what the overall season looks and feels like. Using previs and storyboards, each director essentially animates their entire episode and every single scene. Through that process, you put each scene up on its feet and realize that somethings aren’t working: this scene doesn’t make sense or this shot should go somewhere else.

Then every director screens the episodes and Jon uses that process almost like a writer’s room. By the time we’re actually shooting, the script ends up getting rewritten based on where the previs landed. Essentially, each one of us are cutting and completing our episodes before we ever shoot. Because of that, we can be constantly checking in with one another and need to be checking in with one another. It’s not that we’re together every day; there’s this connective flow where we’re all speaking the same language and watching each other’s backs.

How does your acting background influence your directing style?

One of the reasons why I was hired for The Mandalorian was because Jon himself is an actor. The transition from writing to directing can be very challenging because directing is not just about telling a story, it’s really about running a set. The filmmaking side of the process is its own thing and how to actually get the scenes is something that writers are often not exposed to. What Jon realized for himself is that in being an actor, you’re in this privileged position where you’re right by the camera and get to at least witness those final decisions being made. How the final problems are getting solved so that the thing that needs to get on camera gets on camera. Some of the most important decisions get made at that point. If you don’t know what to do at that stage, if you’re not used to being in that environment, that can be incredibly overwhelming and intimidating. Jon knew that I had been exposed to many different versions of how to approach problem solving and running a set.

How does your directing process take into account the Volume and special effects of the production?

Jon wanted the filmmakers to be experienced in traditional filmmaking because the technology we’re working with on The Mandalorian is so groundbreaking. You want to still abide by the rules of what it’s like on a practical set and when you’re on location, because as an audience, that’s what our eyes are used to. When technology suddenly opens up, there are limitless possibilities. Jon emphasized keeping it grounded. In the Volume, we can have magic hour all day long, but how do you shoot magic hour when you don’t have access to a Volume? In real life, you only get 50 minutes for it, so you’re going to get the priority shot first. Then you’re going to get the reverse, which is less important. The reverse is probably going to be lit artificially, or it’s going to be darker. It all depends on how quickly you hustle.

Jon taught us that if you’re doing a shot in magic hour, you need to make sure that the reverse is something visually more keen to what audiences are used to seeing, as opposed to what we can actually achieve now due to technology. As directors, it’s important that we don’t cheat too much just because the technology is available. A lot of the directors that Jon hired are folks that are comfortable with visual effects, yet understand how to apply scrappy filmmaker principles to the Volume.

Because of the workflow process that Jon really landed on using the previs as a writers room, it’s also necessary to build out all the digital assets for the Volume way in advance on shooting. Unlike a typical situation where you’re flying to a location that is disguised as a planet, you’re building out the digital assets of that planet. Therefore, we directors really need to understand a multitude of things beforehand: What scenes are going to be taking place in this environment? What do we need to be seeing? What do we want to be building into the digital assets on the Volume? What’s actually going to be practical? All of these things are necessary in order to use the technology, but they also lend themselves to a stronger story interaction process.

What lessons did you take from Season 1 into your approach to directing Season 2?

With Season 1, I felt so fortunate to have been invited to be in a position of leadership, so I made sure that I was playing within the boundaries. I was more curious about the process and how to facilitate it. With the second season, I knew where I could take certain liberties in process and story. Whenever anyone is doing something not for the first time, there is more of a sense of freedom, playfulness and just making suggestions that you might not have had the courage to make the first go around.

Your episode in Season 2 had a new planet, space, water, fighting, the introduction of new characters. How do you create balance between all these different elements?

That process really lends itself to being able to have a sense of perspective early on. The trickiest thing about storytelling is losing perspective. It’s heartbreaking to go through the process of creating a film, and then the first time you screen it, you realize all the things that could’ve been better.

Jon realized when working with Marvel that they would shoot the movie for several months, and then he’d come back, edit the movie, and screen it for everyone. The moment he screened it, everyone at Disney and Marvel would give notes on what it needs. Then they would basically shoot for three weeks on the back of the Disney lot, and it would end up being like 70% of the movie. They were able to be very targeted on the reshoots because they had already screened it and knew what was needed.

Because we get The Mandalorian up on its feet so quickly using previs animation and storyboards, and working with the editor and editorial to achieve that, you can feel the balance and when something doesn’t work, even before filming.

There was a sequence in my episode where I didn’t feel right during the previs process. Then I realized that we didn’t have an establishing shot– I asked for it and the VFX department hadn’t designed that part of the planet yet–so we didn’t understand the environment yet. Without screening the previs before production, you don’t realize that you have all those questions. But once you screen it, you see everything your episode needs. We’re all used to being an audience and we’re all pretty savvy. So how can you put on that cap as a storyteller?

There was all this talk of how the scene in Chapter 11 where the ship re-enters the universe is a homage to Apollo 13. At what point in prep did you decide you wanted to do that? And what did it feel like to really capture that homage on film?

It was so fun. Early in prep, we pulled references from different movies, and I remembered that Apollo 13 had quite a number of applicable references. That’s something that plays a role throughout every episode and every single scene. You go to movies and shows, look at other people who’ve done it well, and you steal and borrow accordingly. For me, what was really fun is that I know Apollo 13 so well because I was on set every single day. I watched dailies during lunch. I remember the challenges that came with that film—how to capture weightlessness and all of that. Early on, I knew we had a shot of the ship going through the atmosphere and that we could sell that it was landing at a really terrible angle if the fire is that much more immense because I remembered the similar scene in Apollo 13. It helped inform me when we were cutting in the references. There was one time where I even called my dad and asked, “How did you shoot that close up with the water dripping?” He walked me through all the steps.

Is there a formula to building The Mandalorian that you have to stick to? Were there any shots or decisions reflected in the finished episode that were uniquely yours?

What’s awesome is that once we’re shooting the episode, we throw out the previs. The previs is there to help develop the show, the episode, the storytelling, the script, and of course to get all the assets developed. But when we’re actually shooting, we will constantly make adjustments. When we’re editing, Jon is so great about being really diligent to watch the dailies over and over to discover something new, and build again from there. As is typical of all filmmaking, so many episodes were reinvented in the editing room.

One example of this: at the very end of my episode in the second season, Mando is flying and the baby is in his seat and he sees this octopus-like spider creature crawling towards him. When we were actually shooting it, there hadn’t been a final beat written. It was just that they leave on their ship.

So Jon was like, “What if the ship is super messed up because the Mon Calamaris really didn’t know how to put the ship back together? It’s being held by fishing twine and wire. It’s ridiculous.” That was something fun that came up the day we were shooting it. And then I felt like something needed to happen where baby is in jeopardy, so that you just get that one final beat of like, Mando’s such a great dad. Mando always saves the day when it comes to baby.

When we were shooting it, we acted as if the ship was shaking so much that a piece of the ceiling dropped on baby and then Mando reached back really quickly and caught it before it landed, but it didn’t really work. The piece of the ship didn’t seem quite deadly enough. In post, we kept wondering: could there be another threat? Could we use something from the footage and plates that we shot, but create something else? That’s how the spider octopus came about.

What are some of the best practical lessons you’ve learned from Jon Favreau?

A big one is what I said in terms of working with visual effects of just making sure that you’re shooting in a way that allows everything to cinematically make sense to an audience that’s used to watching movies a certain way. Those reminders of the foundation are really important. Another thing is going back and rewatching dailies. He has a process of doing that that he has taught me: go back and mark if there’s anything weird, interesting, something you might not know what you would use it for. Make note of the happy accidents, the random stuff that were a little bit magical, whether or not it relates. Find those moments and build around that.

In terms of performance, I come from a background where I’m a trained actor who did Shakespeare. Jon taught me to ensure that the acting doesn’t feel Shakespearean, because the world is so Shakespearean. Keep it honest and do whatever it takes to get there. His writing and directing style lends itself to naturalism and I’ve loved picking that up.

What’s the biggest piece of advice you can give to other directors?

I teach an NYU class for the drama program. The students in the drama program don’t really have access to the film program at all, which is a huge disservice. I feel like anyone in the creative industry needs to be able to be a multihyphenate. If you’re an actor, be an actor, writer, director. If you’re a director, be a director, designer, activist, producer. Be clear about what your hyphenates are. You might not actually have work that represents your other passions yet, but be proactive about getting or generating work in those fields. In the class, I give each student $500 to do their own short film. For the majority of them, it’s their first time ever creating their own work. That’s a really intimidating moment, but the moment you do it, it’s like ripping the bandaid off and then you’re empowered. You realize that you can make your own work. You also meet a lot of great people and it opens up a lot of new pathways and then onto the next. Over time that just builds up. The advice that I always impart to my students in particular is to continually generate your own work, even on the smallest level. Even if it’s just on Instagram, keep creating, keep making.

The other piece of advice would be to constantly be in an educational environment where you are collaborating with others not for the purpose of trying to be the most successful, but to push yourself. This woman named Joan Schekel has this thing called the Directing Lab and I’ve done that for years. In order to keep improving, I need to not just grow, but learn new skills that are applicable in this industry. It has helped me creatively and it has helped me financially because when I’m not getting a directing gig, maybe there’s an acting gig. When I’m not getting an acting gig, maybe there’s a directing gig. Now writing in the mix as well.

Bryce Dallas Howard

Bryce Dallas Howard continues to work both on-screen and behind the camera. As a filmmaker, Howard directed on both seasons of the highly anticipated live-action Star Wars series, The Mandalorian. Her behind-the-scenes work for season one of the show is available on Disney Gallery: The Mandalorian. She also directed and produced the feature-length documentary, DADS with Imagine Entertainment on AppleTV+. As an actor, Howard starred in Paramount’s Rocketman, the critically acclaimed biopic about musical legend Elton John, and recently completed the third installment of the Jurassic World franchise: Jurassic World: Dominion.

Howard has directed for multiple campaigns such as Canon’s Project Imagination, Moroccan Oil’s Inspired, Vanity Fair’s Decade Series with Radical Media, and Glamour Magazine’s Reel Moments.Howard has also directed for MTV’s Supervideo: M83’s Claudia Lewis, Sony and Lifetime’s Five More: Call Me and the short film, Solemates in conjunction with Canon’s Project Imagination: The Trailer, which screened at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival. She has received numerous accolades for her work, including being shortlisted for an Oscar in 2012 for her half hour film When You Find Me. Howard also produced the Sony Classics film Restless with director Gus Van Sant. Restless was featured as part of the 2011 Toronto Film Festival and opened the 2011 Cannes Film Festival Un Certain Regard selection.

María Alvarez

María Alvarez is an internationally recognized Cuban-Dutch filmmaker. She graduated from the University of Southern California with a BFA in Film & Television Production in May 2019. Her passions are centered on raising awareness for diverse female stories about sexuality, identity, and coming of age. Her films have screened at dozens of festivals such as the Los Angeles Film Festival and Cleveland International Film Festival, won awards from institutions such as Google, and screened in museums like MoMA. Her short film, "Backpedals", screened at the 2018 Festival de Cannes in the Court Métrage and was a finalist in the 2018 Horizon Awards, an all-female Sundance sponsored fellowship. She is a YoungArts alumna and is featured on the 2018 YBCA 100 List. She worked as a Director’s Assistant to Benedict Andrews on Seberg, starring Kristen Stewart and shot by Rachel Morrison. She is in the festival circuit with her senior thesis film, "Party of Two", which premiered at Outfest Fusion. She is currently the Creative Editor at FREE THE WORK, the global talent discovery platform for underrepresented creators founded by director, Alma Har’el.