Em Weinstein is a writer/director from New York City and The Dalles, Oregon. Ari Damasco is an actor and consultant from Aguascalientes, Mexico and Southern California. The two met in 2009 at Smith College and have been close friends and collaborators ever since.

Em and Ari both live on the afab (assigned female at birth) trans-masculine spectrum: Ari uses he/him pronouns and Em uses they/them pronouns.

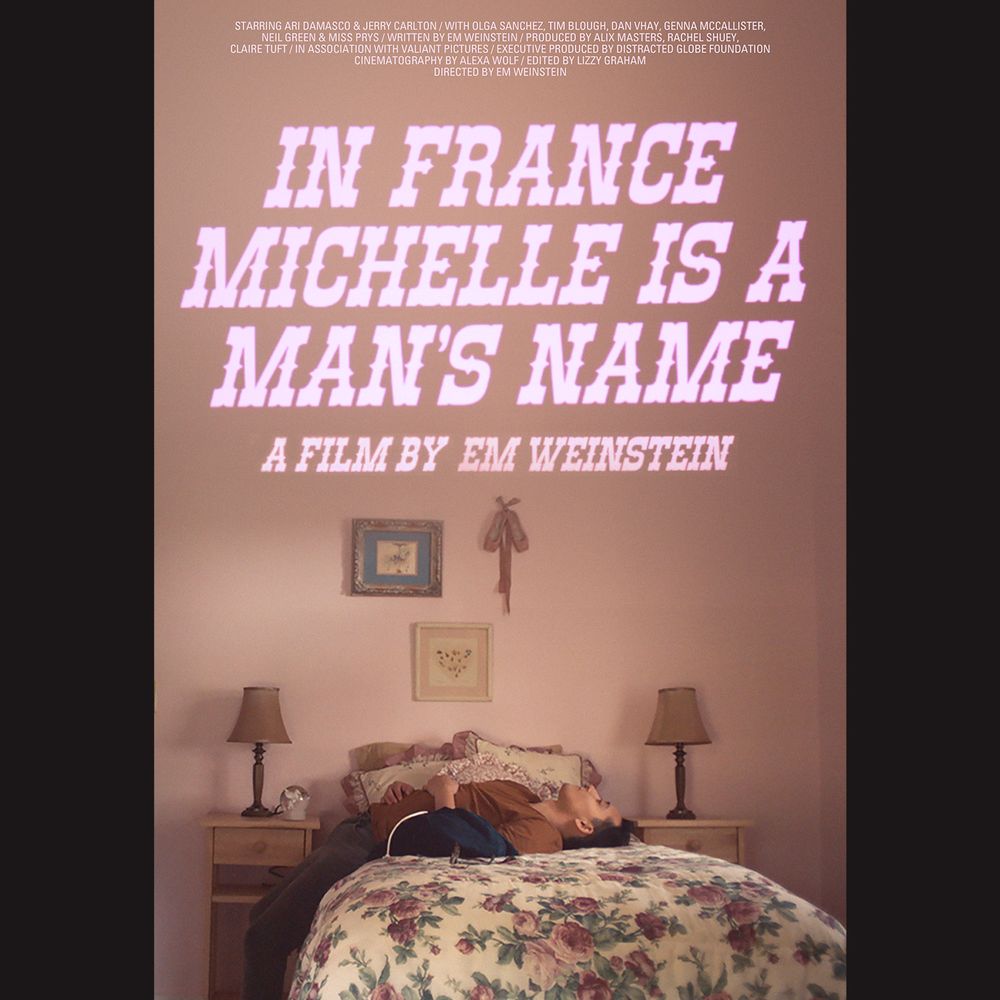

This year, Em and Ari collaborated on a 12-minute film, "In France Michelle Is a Man's Name." The film is about trans identity, masculinity and fatherhood. In it, Ari plays Michael, a young trans man, who returns home to the rural American West after years of estrangement from his parents. Em and Ari spoke over the phone about their reasons behind making the film and the conversations they hope it inspires.

Check out the trailer for "In France Michelle Is a Man's Name" below.

Em Weinstein: When we first started daydreaming about making a film about the trans-masculine experience, we spoke a lot about our childhoods. I think the public is pretty used to hearing trans adults reflect that they’ve known since birth or early childhood that they were “born in the wrong body," but for a lot of us it was way more complicated than that. I’d love to start by talking about the way you perceived gender, in particular masculinity, as a child.

Ari Damasco: When I was a kid, my gender kept me from doing a lot of things like being allowed outdoors alone, or playing soccer, or even just wearing pants. For the longest time that was the biggest fight with my mom: she would insist on dressing me up in all these cute little dresses, very feminine, very much the doll that she'd always dreamed of having. Do you remember John Travolta’s character from Grease?

EW: Danny Zuko!

AD: Danny Zuko! I convinced my mom to buy me a little pack of white shirts, undershirts. And I would wear them under my clothes and as soon as I would get to kindergarten, I’d take off whatever I was wearing, and roll up my little white t-shirt at the sleeves like Danny Zuko. I thought I was the coolest.

"I want cis men to watch this movie, to read queer theory, to think about their gender as a thing to be unpacked and questioned."

— Em Weinstein

EW: You were! I grew up in a very different landscape in many ways had a lot of freedom and privilege in expressing my gender identity. I was allowed to wear boys clothes and baseball hats every day and play baseball even though I was really bad at it.

AD: But you looked cute in the hats!

EW: Exactly! My mom always said: "You can be a girl and wear all these clothes and it doesn't really matter," even though in other moments it was a big fight for me to put on a dress. I always wanted to be a boy, but I never really understood— I still don't understand—if that was because of something inherent in the way I perceived my gender, or if I just I liked the clothes and the freedom and the power that comes with masculinity. It’s a mix of both probably.

AD: For me, masculinity was this thing that felt close, but also far away. It was the antithesis to what my mom wanted me to be. Masculinity was associated with violence, with freedom. It was largely defined by my dad, who I love dearly, but who was very much a troubled man when I was younger. I find that my experience of gender now that I'm 30 and I'm more comfortable with my gender expression is almost a pendulum. It really varies day by day. When I first started taking hormones, there was this excitement about swinging that pendulum all the way to masculinity. Like setting it to 12 on a 10-point scale. In understanding our own genders we find this promise of legacy, of carrying on in the footsteps of the people who came before us in these rituals that are gender-based. I grew up with some really shitty examples of men and I knew I never wanted to be that way. I think that kept me from totally going off the rails because I at least had a model of what I didn't want to replicate.

EW: We’ve spoken a lot about how trans-masculine folk can participate in a culture of toxic masculinity and misogyny when passing in the cis-world. In many ways that phenomenon—and wanting to dissect it, to understand it—is what led to this film. The story hinges on a ritual of toxic masculinity that’s used as a way for a father to connect with his trans son. It’s very much a study of that legacy you were talking about. Our main character has to decide what kind of man he wants to be, and whether he’s going to take up his father’s legacy or ultimately reject it.

AD: Do you think the film holds the promise of Michael and his dad being able to heal their relationship or become closer?

EW: Some people, in watching the movie, might read it as a tragedy in which the father fails the son, but I don’t see it that way. I think if I did, I wouldn't be able to have any hope for reconciliation between queer children and their ignorant, but loving, parents. Because in so many ways, parents fail their children over and over again, and we have to find ways to keep loving each other.

AD: We are constantly betraying each other. We're constantly at battle with ourselves, with society; the things that we want, the things that are expected of us. Loving someone will inevitably give you many opportunities to fail the other person. We have to be constantly recalibrating how we're seeing one another because we're always evolving, we're always changing. And I don't know. I feel like there have been times when I've seen myself play into these roles.

EW: What’s an example of you playing into those roles?

AD: I went to a car dealership once with a partner. The dealership was run by a quintessential cis-male car salesman. My partner is female presenting queer, they/them. I am queer male-presenting, he/him. The car salesman directly bypasses my partner to focus on me, and directs all questions to me. And I’m thinking: “I’m going to help get a better deal for my partner,” so I willingly play into this. I start joking with him in his gross misogynistic way. There are betrayals whenever you decide to side with the toxicity that sometimes presents itself in really benevolent ways. But when you pause and reflect and realize, "This dude made that joke because he doesn't value my partner's femininity, and I just played into that.”

EW: There's a danger obviously in subverting that. Especially as a trans person, which is I think, in part why I want cis men to watch this movie, to read queer theory, to think about their gender as a thing to be unpacked and questioned.

AD: Let's say that a cis man who hasn't questioned his gender, watches this film, how would you hope this resonates with him?

EW: I’d want him to notice the ways in which he has participated in both sides of this father/son relationship. I think it’s about the blinders we have on, and the ways in which we don't see the people closest to us, like our children and our parents. I want parents to see this film and be able to be more open-minded about their children's experiences of walking through the world, but also I want kids to see it and realize that their parents are often trying really, really hard, but don't necessarily have the tools or the language we hope they do.

"When we dissect constructs and power dynamics it’s always going to be messy and clunky because we're conditioned to NOT question the systems that keep us compliant with the status quo."

— Ari Damasco

AD: I love that. I truly love that. I think that that last point resonates the most with me. This idea of a relationship between parent and child that exist two different worlds but still love each other. They love each other in a way that is messy, not perfect. Just like this conversation. When we dissect constructs and power dynamics it’s always going to be messy and clunky because we're conditioned to NOT question the systems that keep us compliant with the status quo.

EW: Agreed! Which is part of why I think trans folks have to be ones leading the way. We’re used to living in this uncomfortable messy questioning-stage. We’re able to turn to our cis siblings and parents and say: "I know gender seems confusing and complicated and guess what—it is!"

AD: I’m fascinated with this idea that a healthier masculinity is possible. There’s often a lot of emphasis on what men do and what masculinity is or isn't. I would love to play around with the idea of masculinity from a feminist perspective.

What does it look like? How can you find the softness within the masculine conception of gender? How can you find compassion and all of these wonderful and beautiful traits that we usually associate with femininity? How can we make this part of masculinity?

Em Weinstein

Em Weinstein is a writer and director for stage and screen. Em’s award-winning short film CANDACE played at festivals worldwide including Mill Valley Film Festival, Outfest, Montclair Film Festival, Rhode Island International Film Festival and the American Pavilion Emerging LGBTQ Filmmakers Showcase at the Cannes Film Festival, where it won Best Film. While getting their MFA at Yale School of Drama, Em directed numerous plays such as the first workshop production of SLAVE PLAY by Jeremy O. Harris. Em has written, directed and developed work with companies such as New York Theater Workshop, Rattlestick Theater, Shakespeare & Company, Two River Theater, Working Theater, New Georges and the Museum of Ice Cream. Em is currently under commission by En Garde Arts and the Yale Center for British Art. Em is the Artistic Fellow at Rattlestick Theater and part of the AFI Directing Workshop for Women Class of 2021. Em identifies as nonbinary and uses they/them pronouns. www.emweinstein.com.