For Terence Nance, intention is everything. It’s evident in his work. Just one viewing of the Random Acts of Flyness and you’ll understand. He operates from inner purpose and necessity—not form, structure, tradition, nor creation for its sake. If he puts it out, it means something, because to him there are too many things in this world that don’t. Here, the multi-hyphenate artist, whose signature aesthetic is an amalgamation of every aesthetic imaginable, unravels the “why” to his work: collective healing.

What influenced you and your imagination as a kid?

Terence Nance: I grew up in Dallas. In the ‘90s, Dallas and Houston were big cities but they were still rural in a lot of ways, so there was the ability to just go sit in the creek and let time pass. I had a lot of idle time in that in-between space of nature and suburbanization.

A lot of the things going on around me were influential. Mainly what I experienced in church. It was a progressive, communal African-centered church that was growing and very deeply Southern and black. I also read a lot of Roald Dahl. Not just the kids books, but the adult stuff and short stories, too. Something about his way of processing British childhood was really informative and inspiring.

I remember I found a black and white TV in the garbage, and I put it in my closet. TV culture at that time was most weird late at night…I watched I Love Lucy. It was like 8 p.m. or something. I think my parents knew I had the TV in the closet. It was just me in that closet—it was too small for my siblings. Something about the texture of that experience with TV is present in how I imagine things now.

What was church like?

It was like the main social environment. You had a crush that was at church, you had a best friend from church, you probably had a beef in this church. I was on the basketball team at church. I used to film the church services as a part of what was called the “media ministry” and that’s also where I learned how to edit. I would go three or four times a week because of choir rehearsals and stuff like that. It was a multi-faceted experience.

I was very lucky because the intentions of the community were very affirmative of childhood and being a kid. It wasn't the type of church that had an overly stoic or aesthetic idea of what a childhood should be. One day, you got an Easter egg hunt, another day we had camp. Class barriers are also broken down at church, ‘cause people from all kinds of different classes and different neighborhoods come. That was pretty special.

What currently inspires you and your work?

I think a lot about neural networks, sounds, and images and their effect on individuals and communities. I think about how to make a positive impact on the body and how different stimuli make me feel. I also think a lot about the function of storytelling and stories, and the function of sincerity, humor–the utility of those things. I think a lot about usefulness and my responsibility to my family and the people around me.

What do you think is useless?

There's a lot of stuff that's useless. One thing that's particularly useless is materialism as a daily practice. It doesn't have utility. It's useless to just entertain. There's a lot of useless suffering out there.

Why do you participate in an industry called the entertainment industry?

I participate in it as an anomalous fact of life. I make work in a medium that's distributed in channels that mostly contain other media that is made to entertain, or to occupy. So, name a reality show.

Love & Hip Hop.

The Bachelor.

Okay, The Bachelor.

Yeah, The Bachelor's just trying to entertain, and it's on TV. So I do a thing and it's not to entertain, even if it's on TV. They’re both video files and TV’s just where it's distributed. But the The Bachelor's useless. Its only use is to occupy the people watching it for a certain amount of time. That's it.

What would you say to someone who watches it to cope, to self medicate, to feel better after a shitty day?

The self-medication that which you're pointing to is a sign of some sort of pain or suffering or sickness that is not actually being medicated by the act of watching The Bachelor. If you are suffering, The Bachelor's not medicine. Actual medicine is immersing yourself in a therapeutic environment, whether that’s taking a bath or talking to somebody consistently in a transparent way. There's actual medication to whatever suffering is happening. The Bachelor is, at most, a distraction. It can be said that the person making The Bachelor is not intending to medicate you. They're intending to occupy you.

Whoever made the game chess intended to create a tool that will occupy you, but also train your brain to think of strategy and scenarios in opposition to another human brain, which is a highly useful skill. It could still be entertaining to play chess, but the thing that's happening neurologically is useful. There's essentially no board game version of The Bachelor. Part of that is because the nature of any board game is that you are in conversation with another brain in that moment. That alone means that your brain has to be active. You're not just occupied, you're engaged, and that's what I do. Everything I'm doing with my work is engaging. That's why I call it engagement not entertainment.

Why did you choose a camera as a medium and a screen as your means of engagement, distribution, and storytelling, among other things?

When you're doing something with a screen-based media, it has very specific neurological effects. So much shit is destructive and either totally innocuous and intentionless, or explicitly designed to hurt or destroy, or shock, or just occupy. So, you know, this whole shit is a game, you got to get in the game. Nazi Germany had a department of propaganda for a reason and if we as a society have a chance of surviving that type of info war there has gotta be counter-programming. There has to be counter-programming that’s as consistent as the “channel” telling you you need to “build a wall.” It's important to have a positive neurological effect on children, especially black children, that contributes to healing and self-healing, self-actualization, and self-love.

"You’ve got to embolden, especially the kids around you, in the way that you were. It’s important as black men, especially cis men, who have access to the TV industry to make space for black women and, you know, black people across the gender spectrum."

Can you expand on that importance?

Well, for me, as a black kid in America, the media fosters self-hate. The biggest challenge is finding a way to counteract that psychological warfare by encouraging people to look in the mirror and love what they see. The FCC has these policies about how much news has to be on a network for them to get their license. It should go farther. Children's programming should be required to espouse self-love and advice of self-acceptance for children. It should be required to be affirmative of all genders, skin tones, and sexual orientations. That kind of counter-programming is necessary for Black people to make as a community and it should be widely available, widely marketed.

Who are some creators you see doing this, creating this counter-programming and contributing to healing?

A few films come to mind that need to be watched. The first is a film called Jinn by Nijla Mu’min. It's a coming-of-age story about a black girl interacting with Islam in a way that reframes what is publicized as blackness and religion in general. This is really something you don't get to see, you know what I mean? And then another one is Tchaiko Omawale’s film Solace. It's a movie about a black girl dealing with body dysmorphia and eating disorders. These films need as much marketing as Ladybird. Like any other coming of age movie.

The one [coming of age film] that came through [in the mainstream] obviously was Moonlight. It shows boys being intimate with each other along this huge spectrum of intimacy that is not available to society’s current understanding of black masculinity because of patriarchy. It’s about healing; the story shows black kids in a light that you never get to see.

Were there any programs you watched as a kid that were particularly transformative or healing?

I was most attracted to Fresh Prince. [Laughs.] That was cool because it showed how when you're a black kid, the white world expects you to act a certain way. But you don't have to change, you don't have to switch it up. Carlton represents what happens if you constantly switch and Will represents what happens if you don't switch—and Will wins mostly. People miss how important of a message that is: You don't need to switch.

There was also Reading Rainbow. It was really important to show the imagination that comes out of reading. And the Spike Lee films—Malcolm X in particular. It came out at the time when we read the autobiography of him when I was seven years old.

"It's just important to contribute to the culture that created you or sustains you."

What are the ways you’re creating counterprogramming and opportunities for historically marginalized people?

Yeah, I mean, I produce films. We're producing several features at MVMT—Naima Ramos-Chapman’s two feature films, Tayarisha Poe’s feature…I’m just trying to produce as much as possible, as much of that work as possible and trying to make as much space for [my community]. Because that's the community that enabled me to exist, you know what I mean?

It's important to contribute to the culture that created you or sustains you. I came out of a community of black artists who are super vigilant about supporting me. I don't think I'm doing anything extraordinary. What I do is like a bodily function. It's like something I’ve got to do to survive at all. You’ve got to embolden, especially the kids around you, in the way that you were. It’s important as black men, especially cis men, who have access to the TV industry to make space for black women and, you know, black people across the gender spectrum.

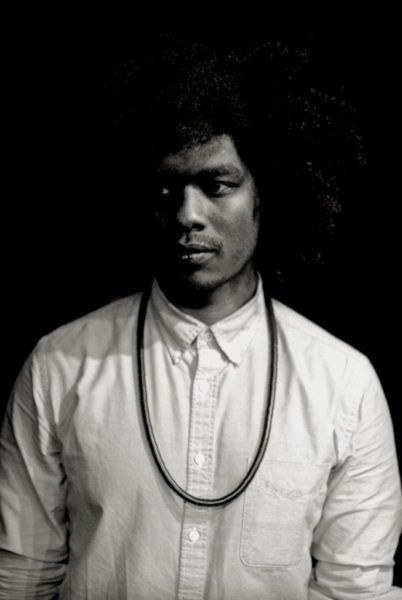

Terence Nance

Terence Nance was born in Dallas, Texas in what was then referred to as the State-Thomas community. Nance learned personhood there. Nance’s first feature film, An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, premiered at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival and was released theatrically in 2013. In 2014, he was named a Guggenheim Fellow.

In the summer of 2018, Terence’s Peabody award-winning television series Random Acts of Flyness debuted on HBO to great critical acclaim, and was renewed for a second season by the network. The New York Times hailed the show as “a striking dream vision of race” and “hypnotic, transporting and uncategorizable” adding that “it’s trying to disrupt and redisrupt your perceptions so that, finally, you can see.”

Additional film work includes “Swimming in Your Skin Again” and “Univitillen”, which premiered at the 2016 Sundance Film Festival and the 2016 New York Film Festival, respectively. In 2017, Nance premiered a performance piece, 18 Black Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the Singularity and are Thus Spiritual Machines at Sundance. Nance is currently at work on healing, curiosity, and interdimensionality, and resides in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

Headshot courtesy of http://terencenance.com