On episode two of "FREE THE WORK Focus: Pride," the FTW podcast mini-series, supported by GLAAD, FREE THE WORK's Chloe Coover chats with Disclosure director Sam Feder chat about the creation of the documentary, how media plays a role in the development of trans folks, and the fellowship model that fostered a game-changing learning environment on set.

Subscribe to the FREE THE WORK podcast on Amazon Music, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, and Soundcloud to listen to this episode and get updates on the next one!

Then be sure to follow @GLAAD and @FREETHEWORK across Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.

Scroll down for the full transcript of the episode!

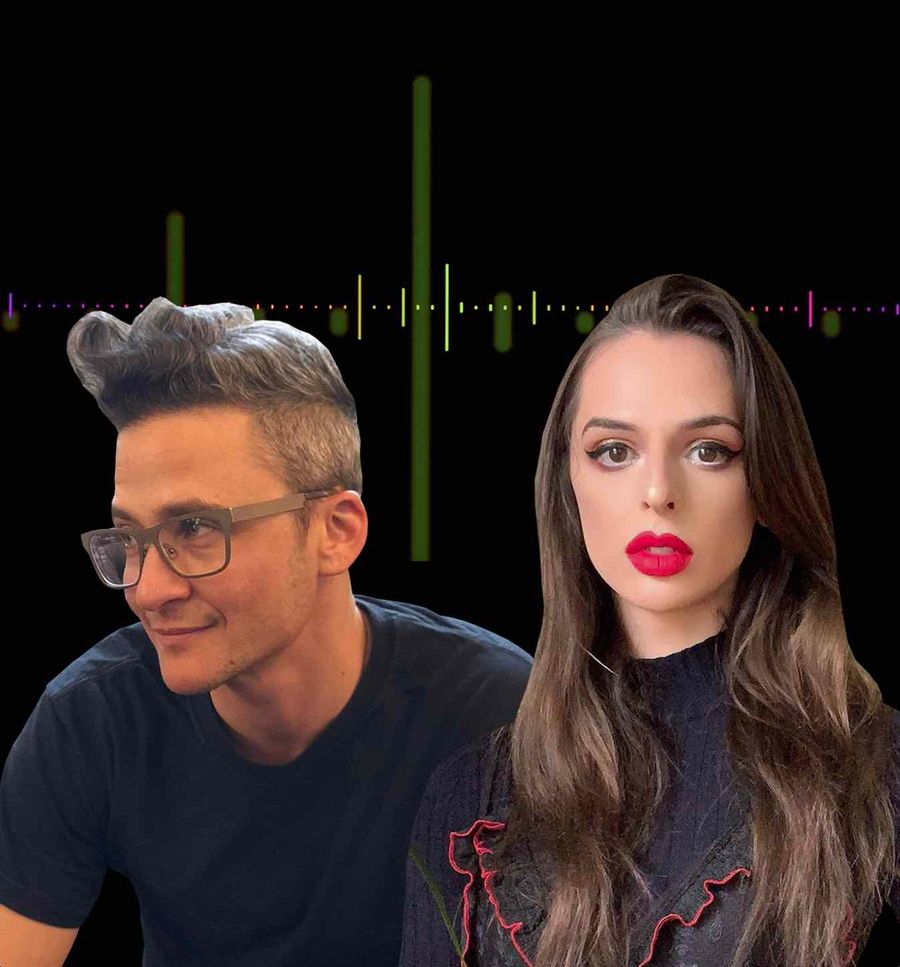

Chloe Coover

Chloe is FREE THE WORK's Community Lead. She's an artist, quadruple Leo (Sun, Moon, Rising + Mercury), ANTM scholar, meme enthusiast, and is proud to be a woman of trans experience.

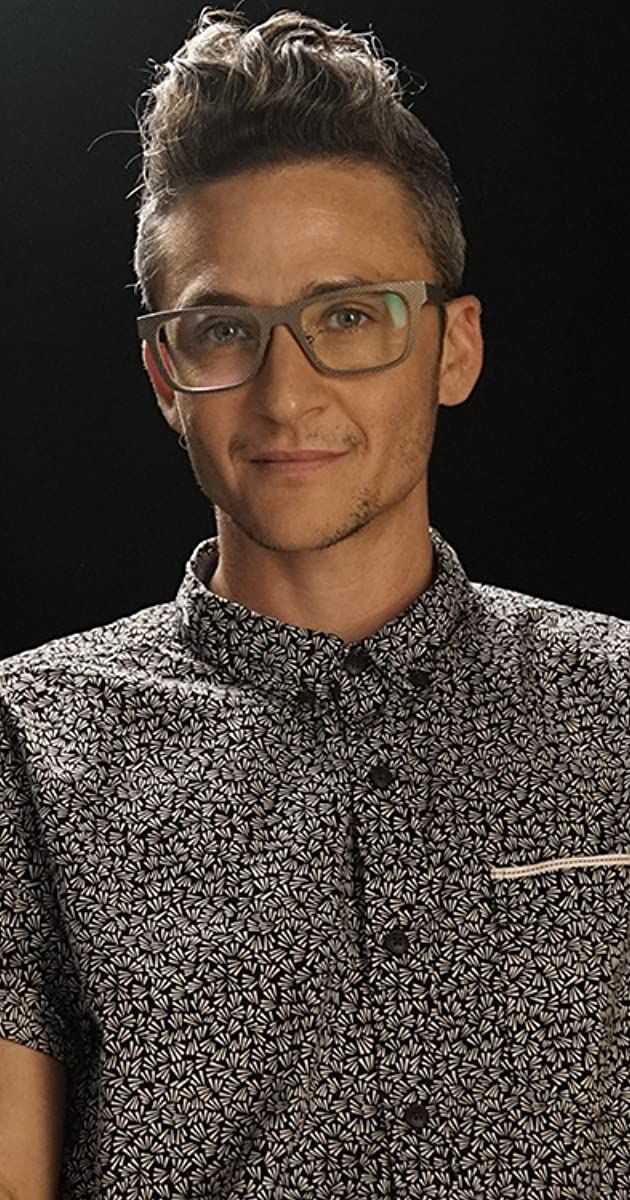

Sam Feder

Sam Feder is a director and producer whose films explore the intersection of visibility and politics along the lines of race, class, and gender in trans lives. Central to Sam’s work is putting urgent activist issues into a historical context. Both The MacDowell Colony and Yadoo have supported Sam’s films as well as grants from The Jerome Foundation Grant, Frameline Completion Fund, Crossroads Foundation, Funding Exchange, Astraea Foundation for Social Justice, and Ellen Stone Belic Institute for the Study of Gender in the Arts and Media.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Chloe Coover: Hi, everyone and thank you for joining us for the FREE THE WORK podcast mini series supported by GLAAD if you're just getting familiar, FREE THE WORK is a nonprofit global initiative and searchable talent discovery platform for underrepresented creators. Just a little disclaimer, the views and opinions of the guests do not necessarily state or reflect those FREE THE WORK. So I'm Chloe Coover, FREE THE WORK’s Community Manager and today I'll be speaking with Sam Feder, a documentary filmmaker whose work includes Kate Bornstein Is a queer and Present Danger. And last year's landmark film, Disclosure, which is available on Netflix. Disclosure takes a look at the troubled history of trans representation in film and television, and provides a deep look at the ways that Hollywood simultaneously reflects and manufactures our deepest anxieties about gender. So thank you, again, for joining us on this call.

Sam Feder: My pleasure. Thank you. I'm excited to have this conversation. Yeah.

CC: So just to start off, I wanted to sort of establish some of the context in which we're having this conversation. So we're recording this the week after this year's trans Day of Visibility, and a week after the Arkansas Senate passed Hb 1570, which bans access to gender affirming care for transgender minors, including reversible puberty blockers and hormones. So just to pull back for a moment when I wrote these questions originally, it was sort of in the stage where the State Senate had passed the bill, but as of today, Monday, April 5, Governor Asa Hutchinson has since killed Hb 1570 because the bill would be and is a vast government overreach and because it would have created new standards of legislative interference with physicians and parents as they deal with some of the most complex and sensitive matters involving young people. So just some additional developments since I wrote these questions originally.

And also one final further point, this could still pass the assembly because they have a Republican majority and all it takes is a majority vote. So mixed bag, good and bad updates on this. And yeah, just in general, this is part of a larger trend of anti-trans legislation being introduced recently, including those from Alabama and Tennessee, that either are sort of seeking to deny medical care, access to medical care for trans youth, or to ban trans athletes from participation in sports teams that affirm their gender.

And so in the light of all of these redoubled attacks on trans identity, I'm curious to hear your thoughts about the concept of visibility for trans people in 2021, because I know that from reading previous interviews, you've talked in the past about visibility not being the goal in and of itself. So that's a lot of context to start off with. But we'd love to hear your thoughts on visibility in 2021.

SF: I mean, I think visibility brings a lot of paradox to it. And you know, that that was the impetus for making Disclosure, right, was the paradox of increased visibility, because with increased visibility comes increased vulnerability. I mean like, we saw the more that trans people were in the spotlight, the more social and legislative violence ensued. And that's not unique to trans people, whenever a marginalized community gets mainstream attention, backlash ensues. And that's usually because of what the mainstream has previously thought of marginalized people because those images- that they're that- because their relationship that most people have with marginalized people is through the media, right, like because people live isolated and stay amongst themselves. And so we've learned a lot about each other through mediated images.

But just to circle back to the rise of social legislative violence, along with the rise of disability of trans people, it's not a one to one relationship. There are other things that work, and certainly a lot of what we saw, I think five, six years ago with the increase of legislation, a lot of that was kind of coming in place of the space that Marriage Equality would have taken up before. Right? So as soon as that wasn't the legislative football then trans lives became the legislative football. That's just some background to the entry point into making Disclosure. So visibility is really complicated.

I think there was a point where, to me, it felt a little more clear that we needed visibility at whatever cost. But then as I started making work and seeing it in the world, and understanding what those costs were, it got a lot more complicated for me. So when it comes to the state of visibility, now, it's also complicated, because it's highly curated, it's highly glamorized. And that is just not realistic, it doesn't reflect the true lives of trans people. And when we're still living in a state of trans women, specifically Black trans women being murdered at you know, epidemic proportions, it's really dangerous to have such a myopic reduced image of people in the media. Maybe there are some people who need to see these glamorized images, right? We all need to be seen, we need role models, we need to be mirrored in whatever way possible. That's what we need to be visible. But I still worry about the state of where we are now, because it's so unrealistic and leaves and just reduces the real lived conditions to a success that very few people can reach and enjoy and experience any life changes from within.

But I mean, what's also fascinating is so many more non-trans people are reaping the benefits of trans visibility. Right. It's literally the bottom line, like the people who've made money off our stories who are not trans, right, the people who built careers off our stories who are not trans. And I made that certainly in my mind in making Disclosure that everyone interviewed would be trans everyone working on it would be trans or have to be training and trans person. I mean, I wanted as many trans people to benefit from the making of a project, not only because trans people need to be to benefit from the stories when it's become a commodity once it's a commodity, it's just this moving train, and it's a little out of control. And I just wanted to kind of intervene in this moment and try to just help distribute that a little bit. Yeah, I can go on about the- the paradox of visibility-

CC: Yeah, I think that it's so fascinating, because it does sort of go back to the roots of what the historical moment, which I was reading from other interviews with you about where Disclosure sort of came to be was, in your thoughts around sort of the initial media coverage of what was in 2014 or so the trans tipping point, and sort of your feelings about how that was potentially a misnomer, or just misinterpreted sort of wave of visibility, that wasn't always going to be in service of the the lived experiences of actual trans folks. And so, yeah, I mean, I don't want to put words into your mouth about that, either, if you want to speak to sort of the conditions that led to the creation of Disclosure.

SF: Yeah. I mean, the cover story you're referring to with Laverne Cox, on the cover of Time magazine, she was the first out trans person, trans woman to be on the cover of Time magazine. And I had known her from activist work in New York, and so I knew she would be an incredible spokesperson. And I was thrilled for her to have that visibility as an actress. But yeah, it felt really strange again, to have the mainstream declare. You know, by the time that cover story hit the newsstand, the mainstream had barely noticed trans people, let alone celebrated trans people. So here, there was a celebration sensibly there's a tipping point, but it's for one person, right? One person is representing all of this.

But in the world around me, the trans people around me were still experiencing disproportionate unemployment. I think it's three times more. I think trans people are three times more likely to be unemployed compared to the national average. And it's four times if you're a trans person of color. And we're also lacking access to housing and health care because of that unemployment, obviously, and the other discrimination we face in those places. So and as I mentioned a moment ago the epidemic of trans women, Black trans women being killed trans guys experiencing a surge of suicide. I mean, this was what I was seeing around me, and this is what is still kind of the state of affairs.

So not only did it just feel like they were saying something in our name that was so not true. What is the word? It just felt like such a lie. It just felt like such a lie. And it felt like well-meaning people around us thinking this was the moment to celebrate. As I suggested – ‘Wake up. No. Don't be so silly. Don't be so easily swayed.’ You know, the well-meaning liberals who believe every headline they read in the New York Times, it's like that audience who was like, 'Oh, everything's great for you guys now,' And you're just starting to understand that gender and sexuality are different. And now you think everything is great for us.

So then I wondered what had indie filmmakers, like myself, who had been making work at that point for 10-plus years- were we accountable in this? Like, did the work we had put into the world influence this at all? And on one hand, what is our responsibility in taking this turn that I didn't think was good? And the second part, where were we getting opportunities? Right?

But then ultimately, I was scared. Ultimately, I knew that the backlash would increase because now people had a target. Now, people are going to have more references to us. And absolutely the backlash has increased, largely due to visibility. Again, it's not a one to one. There are a lot of things that contribute to it. But people became more readable as trans. And then the general public started to have more of a reference point, more of a vocabulary, more of a target. And therefore the politicians had more to work with. I heard it from people all over the country, from friends who kind of lived in rural America who were not legible as trans and would go about their lives. And suddenly, they were legible as trans and now face more harassment in their small towns. Two people in New York having similar experiences. So it didn't matter where you lived, suddenly. trans people in the majority, at least in our country, were experiencing life differently, because the visibility, and it was not all good. So I wanted to explore that. And I wanted trans people and non-trans people to understand the role that the media had played in creating these mental images that we all kind of had a collective understanding of what trans people are, right?

I mean, I can just speak for myself, I certainly have so much internalized transphobia. So many questions about the realities, like what is real, what isn't in terms of my identity? And I know, I'm not alone in that as a trans person. And so much of that is largely due to the media we've consumed. I wanted us to have this documentation in order to see this history outside of ourselves, see it in a context and see it held and explained by other trans people. So here's the document that not only can kind of show you how and what you've internalized and kind of help you put piece things together. But also, here, it was a shared experience that we've often experienced in isolation and alone. And there is- there is catharsis and shared experiences of pain, there is a way to move past it, because you can step outside of it more you see it outside of yourself. And you understand that it didn't come from within you that it was taught to you.

CC: Totally. I mean, I think I have speaking just personally, I know that that was my experience of viewing Disclosure, as a trans person, I was really fascinating to see all of these trans voices, both sort of affirming things that I had experienced when I had encountered certain pieces of media that were being discussed, but then also voicing very contrary, like beliefs and opinions to the way that I had initially experienced these other pieces of media. So it was a really, I mean, I appreciate anything that serves to help underline how the trans experience like all community experiences is not a monolithic one. And I really think it did that so effectively and I know was that something that was part of your goal in the process as well?

SF: Absolutely. That's part of my goal for many reasons, one, because you know, transness is often so reduced to a singular narrative. Stories about us are often just through one person's experience that's meant to speak for all. And so yes, I wanted to show we have many opinions, many divergent opinions. Also, that just makes for more interesting storytelling, it's creates a tension, but also, it's just a way that you know, Laverne and I were really hoping just to model general conversations in the public that it's always a both and, right, it's there's always many ways of looking at the same thing. And there's many ways of critiquing with accountability, but also with kindness. And it's important to know that the same image that might have been really painful and traumatic for one person was liberating for somebody else. And to be able to hold that truth is difficult. It's hard. But that feels really important to me for media literacy.

CC:Totally.

SF: And yeah, and since media really is the most powerful cultural institution of our time, our society just needs to be more literate in the media and more critical and more engaged as active consumers.

CC: Yeah, I completely agree. I mean, I found it interesting, too, because it was not even just that there were contradictory opinions. Within between different speakers, I, even myself, have experienced moments where there are certain films that include an example of trans representation, where I value the impact that they had, for me as a teenager, maybe, but then now looking back, I'm like, 'Oh, my god, this is so inaccurate or problematic,' or it has these issues that I would probably want to, like, go back and change, if I had any hand in creating it, I would have probably made a lot of significant changes, but it was very meaningful still. And so I think that it was really, really amazing to hold sort of a forum for many different trans voices to unpack all of those things, even from their own personal histories, and then share them so broadly, like on Netflix, in a way that people are going to get to engage with, even beyond the trans community as like a sort of inclusive space, a safe space for the conversation to take place.

But yeah, I mean, so speaking just about the making of the film, we did last year, a podcast mini series that was entitled, “The Future Through Our Eyes”, that I was hosting. And through that, I got to speak with Ava Benjamin Shorr, who's the DP of Disclosure and Nava Mau, who was one of the on-set fellows. Both of them spoke very highly of their experiences on the set. And sort of the intentional way that the fellowship program was created, in order to ensure that if there wasn't a trans person who could be hired to fill a specific role on the crew, a fellow would be paid to come and shadow that role in order to gain professional experience. Do you want to talk about how that fellowship model came to be? And just how it played out in practice?

SF: Yeah it's like this industry, right? The Hollywood industry, in quotes, starting to understand that on screen images are really important. And representation is really important, but a little slower to the story behind the scenes is just as important, if not more, quite honestly. And one should not be sacrificed for the other. And you know, who's telling the story, who's informing the lighting, who’s making people who's greeting people, who's creating an atmosphere on set, completely impacts the final product. From the beginning, I knew. I've always worked with only queer and trans people. I made two films before Disclosure, always sort of queer and trans people, and that wasn't going to change just with Disclosure.

It was a much bigger crew, and so it was a lot more work and a lot more money. We pay everyone on both sides, the camera, everyone we interview because it's a life experience. They're the experts. You know, we value experts in this culture. We pay experts in this culture, but for some reason, in documentary filmmaking, people think you're not supposed to pay the people that you interview. I just think it's so horrendous and offensive. So we pay everyone. We also paid all of our mentees, all of our fellows. So I knew I wanted as many trans people to have key roles on set. And when I couldn't hire a trans person, the non-trans person would mentor one. And so interviewing for every role was a lot of work.

I probably spent three or four months crewing up and interviewing people all across the country. And I knew that there was a standard that the film needed to be because I wanted it to reach a mass audience as it has. So I knew I needed people with a certain amount of experience. And whether it's out of choice or circumstance, there's just a dearth of trans people that have the experience. And so our mentees were meant for people who had zero experience and wanted a foot in the door.

Then when I was hiring people who would mentor the mentees, I had to make sure that they were excited about it, that they got it right, that they understood that this was a really unique opportunity for them as well. That they were beginning, and they would get to learn a lot, and that's a real privilege to be able to learn from someone else's life. Every key role, if it wasn't led by a trans person. Every decision behind the framing, and the lighting was guided by a trans person, which is really significant. And I can go into the details, but it just was never lost on me every day on set, seeing the sensitivity that trans people brought to the roles. And then when there was a non trans person, the key role, the role was still informed by their fellow because their fellow was there giving their opinion and sharing some life experience.

I mean, there's certain sensitivities that you just cannot teach somebody, it just comes from living a life and just having that visceral reaction to the world around you. Then there are also these moments on set that I feel like you were describing as a viewer when people were sharing their stories- it was me interviewing the interviewee talking, so both trans people, and then everyone behind the camera. There was Ava, second camera, the assistant camera, our PA-all trans people. We'd have this space curtain off from the rest of the crew. So we'll just be all trans people sharing these stories. So even in that moment there was this shared laughter, shared pain, shared experiences, which were in themselves really healing and meaningful.

And I didn't expect that to happen, I wasn't prepared for how impactful the actual interview process would be. Also I am very much trained in collective feminism, and collaborative work. And we would take breaks, and I would always ask every trans person on set like, how's this going? Is everything okay, in terms of your job? But also, what would you like us to ask the interviewees? What do you want to see in this film? And for sure, some of the things that came up in those conversations made their way into the film. Nava in particular. Nava is a very, very intellectually curious person. And she always had suggestions, and made the film better.

CC: Yeah, I liked one of the things that she brought up in our interview previously. She was talking about the fact that even though obviously certain people who have onset experience in a particular role are obviously bringing that to the equation, even those who do not have that experience have experiences of their own, that do bring new and unexpected light to the subject matter in question. And she was talking in our interview about how meaningful it was for her to see the sort of differences in perspective that were being brought to the set based on other sets, like in comparison to other sets that she's been on by these folks who maybe hadn't ever had that experience before.

SF: Did you remember any examples?

CC: No, not off the top of my head. But I do think that it just made me excited to hear that because I do think that one of the things that FREE THE WORK is really all about is giving creators, no matter really what level of experience they may end up being, a chance to take a first opportunity in something that maybe they haven't experienced before. And that's a big stumbling block that we hear about from many of our community members in that like 'Oh, I've made multiple feature films, but I haven't had the opportunity to make a commercial, so I'm never going to get the opportunity to make a commercial, which is like good money and like gives me experience with certain equipment that I would never get to experience in the film world,' etc. There are these ways in which the industry, the film industry, the media industry, production industries are so averse to allowing people the benefit of the doubt. And I think that what I love hearing is that in scenarios where people are given the benefit of the doubt, you get new, exciting results, that wouldn't have been possible without that different experience.

SF: Absolutely. Yeah, I think that's really key. Yeah, I don't know, that's beautifully said. I don't really have anything to add to that.

CC: I mean, so the further the final sort of angle I wanted to go on in this kind of questioning is, would you for other productions that would like to follow the lead set by Disclosure? What advice would you give? And how would you advise them to go about making it possible?

SF: Well, I think what everyone is going to hear at some point or another, we did as well, is that oh you just want the best people for your project. And the answer to that is trans people are the best people. And that's just full-stop. And then you're also going to hear there's not enough talent, you're not going to find them. It's just too hard. And my answer to that is making a film is hard. You know, and you get to choose where you put your attention. And you get to decide what you think is important. And if you don't think the people behind the camera are important. You know, that's your prerogative you're making. Right? And it's gonna show it's good. And so yes, it was not easy to have an all queer, mostly trans crew, it was a lot of work a lot of time, a lot of resources. But I knew that was essential to making a good film. And so it was a no brainer. I mean, that's where I put a lot of time and energy and resources.

And I guess the last thing is that it wouldn't have been possible. If Laverne and I hadn't been the ones making this film, because she and I had both been part of the community for 15-20 years. We’ve both been in filmmaking for nearly as long. So we have the connections. It was really between her and I, reaching out to our personal networks and now I have a Rolodex of like, 200 people 200 trans people who are there are interested in working in the industry. And so let's say you're a non trans person, and you have aspirations to include trans people on your set, you're going to have to reach out to trans people to then reach out to their people. We need to have more trans people and decision-making positions, right. And until we see that we're not going to really see true change. So because we have Laverne and I in this film, in this independent film, in decision making positions, we were able to see material change, we're able to see people get work and get skills and better their lives.

CC: Yeah, totally. And I think that that's what we see across the board too. When there are people in key decision making roles, who do have the priorities that are aligned toward making change, that's when you see the change. It doesn't happen otherwise. But so just shift gears a little bit. I wanted to talk about what I'm sure was a very unique process of releasing a film during a global pandemic last year. Can you tell us a bit about what the rollout of Disclosure last year was like?

SF: Oh I'm still figuring out how to tell this story. Some days. I'm like, did it even happen? Sometimes I'm catching up with friends, and they tell me about something, and in my mind, it happened last summer. And they're like, no, it happened two years ago. Last summer didn't happen. I'm like, wow, like, the biggest thing that happened in my career, like didn't happen. I still try to understand that totally.

But yeah in the end of 2019, we were locking this film, we got into Sundance, which was so exciting. I definitely definitely wanted that, and I was thrilled. We got a great sales agent to represent us. We had the great publicist who was coming with us to represent us at Sundance. We were so excited. We had an incredible premiere, about 30 people from the film came. So I think it was the largest group of trans people to ever be at Sundance. And it felt really, really good. And we had an incredible response and great press. Everything's looking good.

We were starting to hear about other festivals. We were getting ready. I bought new luggage at an outlet, which I have finally used. But for the whole year, it was just under my bed, collecting dust. But we were getting ready to travel around the world to all these festivals. And it was really exciting. And going to festivals, it's like, that's where you make all your connections, right? That's where you meet other filmmakers, you meet other producers, you meet future collaborators so much happen.

So many of the people that helped me make Disclosure are people I've met through making my other films and going to festivals, right? So that we still had a very intense year ahead of us. But then within a month, the world shut down, we got back from from Sundance, and very quickly, news about COVID starts taking over the radio, and then things start shutting down. And then one festival after another is closing, closing, closing and the biggest heartbreak for me was when New York shut down, I think Broadway decided to close and that's when Tribeca decided they were going to cancel their film festival. And after Sundance, that was the most exciting festival to get into. For me, it's my hometown. So at that point, I had no idea what's gonna happen, I didn't know if we'd ever screen our film to a public, in person.

Again, I didn't know if we'd have a home because the film had not sold at Sundance. And when you don't sell a film at Sundance, suddenly it gets really scary. And you wonder if you're going to sell it at all, even when you're in a good position to get in there with the sales agent, which is a good thing, but we didn't sell. So by March, when everything was shut down, we really didn't know if anyone would ever see the film again. And that was really scary and sad. And we started conversations. And distributors- no one knew what was happening. No one knew what the market was going to be like. Nobody knew theaters were ever going to open up. Nobody knew if there was going to be an audience. So suddenly, nobody's making offers, and this is just across the board.

But just fast forward. Some offers came in slowly. They're pretty horrible. We just kind of just kept dragging it out. And then it was really interesting with Netflix. They made an initial offer, it wasn't great. But we were going forward with it. And then they came back to us wanting to change some things. And so we negotiated and then got things to a better place. And they wanted to launch it in June, and they were gonna put up the press release in May, and the trailer in May. And then things got really murky. And everything was taking longer than they had planned. And finally, the press release went out. And the trailer during the weekend that George Floyd was murdered. So this was all like, within a 24 hour, 48 hour period. And I was like, I'm not celebrating my film right now, but I had no control over what Netflix was going to do. So we created a lot of language and a lot of posts around this moment and how Disclosure can be part of this conversation.

And I felt horrible. All I wanted to do was be out there on the streets. I was experiencing my own experience with what was happening, I wanted to be of support to as many people as I could. So it was a very strange couple of weeks. And then, by the time it premiered, that's when the uprising had really taken off. So again, having to juggle how to talk about our film on Netflix, while the state of the world was changing.

But again, ultimately, what we found was that Disclosure really added to the public discourse, and it was abuse and so that I was grateful that it was and that there was so much intention among our crew of to the issues that that were for some people as a first time they were talking about these things, right. So that's how things turned out. And I was devastated to not be able to go to the festivals and make all these connections and have those experiences that come with that. But then I do think we've reached a large, much larger audience by going right to Netflix. So that's where we are. I've definitely experienced this whole year on Zoom, which is very strange. We've all experienced Zoom.

My friend Akia published her book in April that she's been working on for a long time. And she likes to say that she's doing her victory lap on Zoom after pouring her life and sacrificing everything into a project. You have these meaningful conversations, but then you just click off and you're alone in your office. You get an award and you're excited, and then you are alone in your office. It's very isolating. So it's been very difficult. But Disclosure has had an incredible reception. It's had an incredible impact really quickly, that I did not expect. I'm blown away by that. So at the end of the day, I'm really proud. And it's done really well.

CC: Yeah, I think that there's definitely something to how broadly available it became because of being on Netflix, that, really, from the outside as a viewer, I thought was so powerful. I was saying to people that I knew I was like, 'I'm just really happy that this exists here, essentially, as an educational tool for anyone if I ever need to direct anyone to a nuanced sort of like, level of media literacy, about trans folks and representation. I can just point them right at Netflix.' And most of the time, I would say that they probably have a Netflix account, or access to one in some capacity and can watch it. So that's really meaningful. I've done a lot of academic reading and study, and I have always felt very funny about privileged access and closed off access to certain kinds of information. And I think it's so magical when things do have a somewhat democratized availability to them.

SF: Yeah, I mean, when we were gearing up for Tribeca, I was speaking with one of our funders, and I was saying I, I'm so excited about Tribeca, but tickets are like 25 bucks and that's a lot of money for a lot of people. Certainly for a lot of queer trans people I know in New York who I think would benefit from seeing the film. And so I was starting to ask some of our backers if they would donate a bunch of tickets that we could give. We actually did that at Sundance, too. And so that was part of our efforts to make it more available, because we knew it'd be prohibitive.

So yes, like you're saying, on Netflix, it's either your eight bucks a month to watch everything you want or borrow your friend's account, like many of us do. So that makes it so much more available. I don't know if we would have been on Netflix had we done the festivals, so I don't know if it would have happened. So despite the fact that the state of streaming and the way Netflix is taking over the industry is very complicated- and I have a lot of feelings about that and opinions about it. It's not the best state for independent filmmakers. The access it's given the film is undeniably great.

CC: I mean, yeah, there's nuances to that as well. It's definitely not all positive or all negative, but it's a new state of affairs, at the very least.

SF: It's a new state of affairs. The one thing that I need to figure out is, there were some people- So, we have a really big impact campaign, a really ambitious impact campaign. To date, we've partnered with about 60 different like-minded organizations, and there were some people that we wanted to work with, and their response was, 'We won't work with a Netflix film.' Right. And I understand that, and I might have had that same reaction. But that was really frustrating to me, as the director who started this with no money, didn't make any money. What we got paid was half of what it cost us. So there was no profit. So it was very hard to accept that way of seeing because my goal is for this film to be used and to help and to make things easier for trans people. To have some people just resist it in the name of Netflix, I understand, but what are we going to do? Stop the opportunity of the world being seen around the globe? I don't know, it's hard. You know, the commodification of our identities is- Maybe I'm over the hill, maybe I'm old, maybe that's like a sign of aging, when you kind of like give up and you're like, well, let's work with what we can?

CC: No, I think it's just part of like what we were talking about at the beginning of the conversation in regard to sort of the double-edged sword of visibility in and of itself, It's all sort of different sides of that coin in a way. And I think that there's really compelling arguments to be made for either point. But at the same time, I do think that it's undeniable that there has been a lot of real value and benefit for it being so widely accessible and broadly disseminated. To conclude this conversation, what's next for you as a filmmaker, both in the immediate future, but also in the long term?

SF: You know, in the long term, gosh, I would love to be able to raise the supports, to have a self contained production company that is all queer and trans people and just work kind of replicating the Disclosure set and the Disclosure model. In the meantime, I'm kind of expanding my opportunities. I'm getting pitched both docu-series and getting pitched docu-scripted documentary features and scripted work. So I'm in conversations with lots of different production companies, lots of writers, lots of producers, and just kind of figuring out what the next project will be.

Previously as this kind of scrappy New York indie filmmaker, I would kind of get stuck on a topic and get really obsessed with it and that would be my one project for five years. I was completely monogamous. Now I'm juggling like five or six projects from all over the place, just waiting to see what's gonna stick. So it's very different. I never expected to be making work- within the industry within Hollywood to have an agent to have representation. I never expected that. So that's been a big learning curve. And it's exciting. It's new things. It's a new way of working, it's a new way of talking. There's definitely a lot of negotiating for myself of what opportunity I'm willing to take and still have self respect. So it's a process, but it's exciting. There's nothing I can talk about yet. But hopefully in the next couple of months, there'll be a few things that I can start to share publicly.

CC: Well, I'm personally very excited to see whatever it ends up being whether it's docu or scripted or whatever direction ends up being. Thank you so so so much for chatting with us. And, yeah, I really appreciate getting to sort of go in all the directions we were able to go in.

SF: Yeah, it's really fun to talk. Those are great questions. I appreciate it. Thanks.