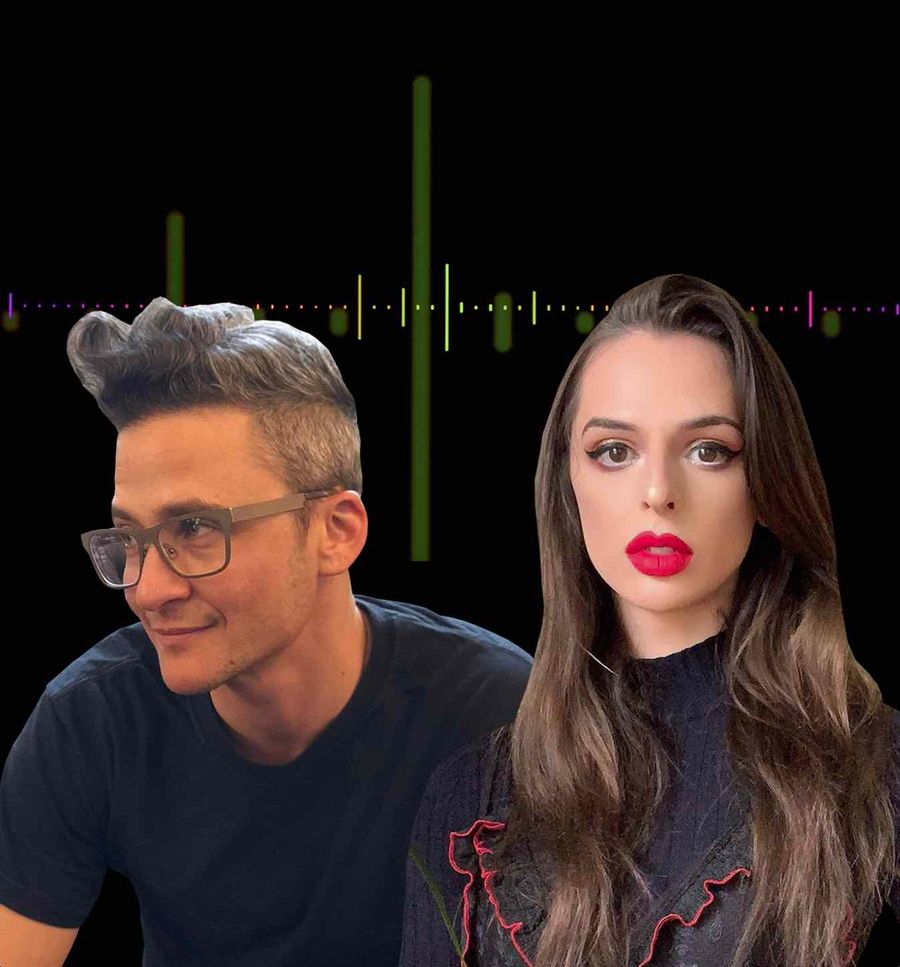

In this episode of our FREE THE WORK podcast miniseries, "The Future, Through Our Eyes," watch as our FTW Community Lead, Chloe Coover, sits down with prolific producer, writer, director, cultural worker, and actress Nava Mau to discuss her expansive body of work, art as activism, and how she plans to use her filmmaking to open doors.

You can watch our close-captioned video below or listen to this episode through Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Keep scrolling for the full transcript! In addition, be sure to watch Nava's most recent work, her short film, "Waking Hour," available to watch on Vimeo.

Nava Mau

Nava Mau is a mixed-race trans Latina filmmaker, actress, and cultural worker from Mexico City and San Antonio, Texas. Nava wrote, produced, directed, and starred in “Waking Hour,” a short film about a young trans woman balancing her safety with her desire for intimacy. She was selected as a Production Fellow for the Netflix documentary “Disclosure,” and she also produced the short films “Lovebites” and “Sam’s Town.” For 8 years, Nava worked in the fields of anti-violence and culture change with community-based service providers, student organizations, and survivors of violence. Her long-term vision is to illuminate the stories of marginalized people in order to transform their access to resources. Nava appears next as a series regular in the HBO Max series “Generation.”

Chloe Coover

Chloe is FREE THE WORK's Community Lead. She's an artist, quadruple Leo (Sun, Moon, Rising + Mercury), ANTM scholar, meme enthusiast, and is proud to be a woman of trans experience.

Chloe Coover: Hi I'm Chloe Coover, Free The Work's Community Lead, and today I'm joined by Nava Mau, filmmaker, actress and cultural worker. Nava is a mixed race trans-Latina from Mexico City and San Antonio, Texas. She wrote, produced, directed and starred in Waking Hour and starred in director Ilana Garcia-Mittleman's short Femenina. She was selected as a production fellow for the Netflix documentary Disclosure and she also produced the short films Love Bites and Sam's Town. Nava appears next as a series regular in the HBO Max series Generation. That's quite a resume and there's so much to talk about in all of that, I'm excited to sort of like break it down with you. Thank you so much for joining us.

Nava Mau: Of course, thank you for having me.

CC: It's so good to see you.

NM: I know it's good to see you, too.

CC: So, in just to start off with, I know that we've talked before this about, wanting the conversation to not just focus on just your work as a filmmaker, but also to touch on the work that you were doing before you were starting, creating films, starring in film, all the different ways in which you're involved in film currently. And so, originally you were working with survivors of violence. I know that's the sort of a thread that's linked a number of your past professional experiences. So do you wanna talk about some of that and how that helps to shift your focus when you stepped into the role as a creator on film, and just, you know, how it affected you as a person?

NM: Yeah, of course. So prior to my work in film, I worked as a counselor with survivors of violence, primarily black and brown LGBTQ survivors of violence. And most of that work was at Community United Against Violence in San Francisco. And the role was primarily as a counselor, I co-facilitated the support group. But the position and the organization's mission are political, so the work was to support survivors in their healing and expand their access to resources, while also addressing the root causes of violence. So for us, that was conducting trainings for service providers around The Bay Area about criminalization and intersecting oppressions and how to support survivors while addressing the root causes. And we also worked in coalition to organize against police violence to resist the expansion of ICE in the Bay Area. It was a really multifaceted and ambitious mission that the organization had. And that's the world that I was very familiar with, in my previous work, so, I bring that with me, I bring those frameworks of anti-criminalization and intersecting forms of violence, but when it comes to what I learned from CUAV, something that I'm thinking of, that I now have as a goal for my work in film is to make sure that I'm doing the tangible, everyday practical work that is needed to change things like in casting, in writing, in the product that people actually receive and bridge that to the overarching complex structural changes that are needed to create a more just and equitable society. And, you know, that's a goal.

CC: Right, you have to have a goal that you set out and then you do the work to, toward it, but it's great to have a very, ambitious goal too, for sure.

NM: Yeah, yeah. So it informs my work every day. That's what I'm here to do is to create a world where we don't have people facing violent situations so that then they have to face the consequences of that.

CC: And I mean, I think it's really fascinating too, because it is the different sort of tracks that your work has covered are sort of like addressing the fact that violence is both an individual interpersonal experience but also structural and, you know, based on larger oppressions that again, as you're saying, like interlock within one another. And so what years were you working on that work, specifically?

NM: I mean, I started in college doing culture change and community engagement work, different community-based programs. So that was in 2011 onward, and then I started working at CUAV in 2015. And then I left the Bay in 2018.

CC: Gotcha, I really liked, I mean, I really liked what you were saying about how sort of the practice of doing the work that was the core of those professional roles remains kind of inherent to what you are doing as a filmmaker and the practice of just like existing in the world from that point forward. Because I feel very similarly in that like, liberation is the goal, you know, and like, I know that liberation entails liberation for not just people who are exactly like me, but people who are experiencing types of, you know, lives and oppressions that are very different from the sets of circumstances that I've found myself in. And without their liberation, I can't expect for myself or anyone I care about to be, free as well. And it is really sort of like, that's the work that you do. And then whatever you do professionally, creatively, et cetera, is in service of that larger ambition. So that really resonated a lot for me too. And I think it's a moment too where a lot of people are sort of, if they haven't been on that journey of realizing how their work can support these larger movements, they're kind of now taking stock to reevaluate and reposition how they can engage. It's a moment that I think has the potential to be really transformative for like, people's day to day actions. And making people more engaged.

NM: Absolutely, and, but there's people who have been doing this work for decades, and every single day and over generations, and I hope that for everyone who is just now recognizing how important this type of culture change work is. I hope that people recognize that we have leadership, right, that there are people that we can look to for guidance, and we don't have to start from scratch. People have been fighting this fight for a long time.

CC: Very true, that's actually, yeah, I mean, I've seen a lot of the impulse from a lot of well-intentioned people being to sort of say, okay, well, like, let's just get started from the ground up, we're gonna build, people who haven't really been paying attention to the ongoing fight for years. I mean, and most of these things that people are putting a lot of energy behind right now, which is amazing, have been ongoing for quite some time.

NM: You know, a century. Like if we really get it.

CC: Yeah, yeah totally. No, I mean, and that's the thing too. It's one thing, just like as a personal kind of anecdote, I have been in this like frame of time, I've listened to the audiobook of The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, which is something that I had had on my list for years and just kind of like, never gotten around to reading fully, which I'm so glad I did, it's so amazing. And one thing that really struck me is that in the earlier chapters when they're talking about sort of these roots of systemic racism, and like the criminal justice system and the roots of like framing populations through the lens of criminality, which is like a really fascinating theme within that book. One thing that struck me so much is that there are these patterns of the ways in which, white communities have been mobilized against communities of color based on sort of class and like proximity to wealth. And there have been times in history where there's been the possibility for these kind of like multiracial coalitions and then they've been sort of splintered by forces that sow racial disharmony. To sort of try to very concisely put, I mean very complicated.

NM: You know for me, that's one of the frameworks that I really, really appreciate from CUAV is black and brown unity. Because as much as we need to uplift ourselves and we need to look inward towards our communities, we have to make sure to be building each other up as well. So that is something that, to be honest, like, I'm really not interested in work, if it doesn't involve a framework.

CC: Yeah, that's real. I mean, and the thing is too, one threads is the fact that that act of being trans, being from the different backgrounds that, you know, the different guests that I've talked to all are which are varied has been something that is inherently political, like and has inherent political repercussions. So it's something that I see all of my guests approaching extremely intentionally and with an awareness of that responsibility and power in a sense. So, from framing it that way, I'd love to talk about what brought you into making film, from that background.

NM: So as much as I pursued a professional path, I have also been building towards working in film since I was a child. I would make these short films with my sisters. I mean, I didn't call them short films. It wasn't like a technical practice, we were just making little skits on this old video camera that my mom had. And then I did this live sketch show, comedy shows in high school, did a little theater in college, so it was always kind of like, that thread was there. But I never thought that someone like me could work in film. It's just didn't occur to me and I didn't really understand that world, especially at the time, but even probably still today if you Google, like film director, right? Like, it's pretty monolithic. The just the images of well known film directors that you see. So I'm not Martin Scorsese, like it just didn't occur to me that I could do this work. And then I found out and I learned about Shonda Rhimes, and I was like, and this was, Grey's Anatomy and Scandal, it was everything, I mean, Scandal, when that happened, it's almost hard to put into words how it felt, right, to have a show like that and the watch parties and it was just, it was a whole moment and so I learned about Shonda Rhimes and that was when I thought, okay, I wanna be a showrunner, I can do that. I can work behind the scenes, right, 'cause this is a time before Laverne Cox, this is a time when, before I transitioned, so I identified as genderqueer at the time, I looked very different, I had a different daily lived experience. And the world around me was very different. So it just was like, okay, yeah, I can push from from behind the scenes. And that became the goal. So I had planned to move to The Bay and be there for five years to develop my craft as a TV writer and move to Hollywood, but of course, I ended up taking a different path.

CC: Doesn't it always seems to go like that?

NM: Yes, and I'm so glad because I ended up making Waking Hour, the short film. It could be just to serve as kind of like a sample of my writing being produced. That was an original intention. I did not know about filmmaking. I did not, I learned it at visual writing. And that was the path and I was like, okay, I'm gonna go to Hollywood with my scripts and my short film, but then it came time to make the short film and it's this tiny budget, and we need a director and we need a star. And you know, I'm like, oh okay, I guess I'll direct and so it just kind of went from there. And my goals changed after I made that.

CC: I mean, it's so fascinating to hear that as the sort of weigh in to making Waking Hour. So Waking Hour is your short film, which is really wonderful. I rewatched it before our conversation and I was struck again by the fact that I was so curious to ask you about what your entry point had been because the writing is really great. But the acting is also so nuanced and like pitch perfect. It's so good, you're such a great actress. And I say that just because it's really, I find it very affirming to see someone play out the kinds of beats that I've experienced in my own real life like the unfolding way that they kind of cascade is really well done. And I really kind of had this sense that, maybe you were more interested in acting first and foremost, and then had sort of stepped up because, you know, you wanted to tell a story that felt true to your experience, and then, but it all kind of comes together and all of the different roles that you've served on that particular short, are, in my opinion, have been done expertly. So it's really fascinating to see sort of like, where you came into it mentally. And then what you've taken from it in terms of where you'll go, where you want to go next.

NM: Thank you so much, Yeah, no problem. I'm so flattered. Yeah, it was really my first time doing all of those things. And I'm very happy with how it turned out given that it was the first time even though I watch it now and I'm like, oh my God.

CC: Actually, that's an interesting kind of conversation to get into, are there things that now that you would do very differently if you were making it again or, that you wanna take into your next projects?

NM: I think that project, that story needed to be what it was, I created a character that was younger than me, in spirit and in physical form. Because of the how long it took to write it, and the place that I was writing from and then what I felt would work in the story, I created a character that just was, just didn't have the same kind of maturity that I have. And and that made sense to me but now I would love to have a project that I think conveys somebody with a different kind of set of experience. And in terms of the acting the of course, I just, you know, yeah.

CC: And directorial, do you think that like you would now sort of bring a different style to it, aesthetically or anything in that frame?

NM: I would have tried to get more money. I had no idea how to just budget for short film. To me $6,000 was so much money and it was so hard to find $6,000. So, we did a crowd fundraiser, hundreds of people donated. Very small donations, lots of volunteers, we shot in people's houses, rehearsed in people's houses. Rafael came up from LA and stayed in my friend's room. It was a very low budget production. And that's also something that it would not have occurred to me that, oh, maybe you can have a much larger budget and the specific things that that can change. So that would be like lighting.

CC: Yeah.

NM: We didn't have a lighting plan. It was me and the DP just doing test shots for weeks leading up to the shoot and then on the day of, okay, this is what works, this is what doesn't and we'll go from there. But I think I would have been more intentional and particularly with the party scenes, and in the bedroom scene, just the colors and the lighting and Imma say one more–

CC: Oh, yeah, no.

NM: I know I can be long winded.

CC: No, I love that. Grader Allie Scott, she did an amazing job decorating the bedroom, but because, she also had to do it in the moment due to budgetary constraints. You know she's not a professional set decorator. She decorated like, the half of the room that didn't end up really being in the shots, because we had to move stuff last minute and just that kind of like, that's what a budget can get you is more time and more professionals who can plan in a different way and collaborate with each other. So little things like that I think would have improved the visual aesthetic of film. And that being said, I'm so proud, so proud of what we came up with and then all the colors, that is all glory to Aja Pop the DP, that's her signature. And I think that in the end, the way that the short films feels, is a reflection of the collaborative and real grassroots effort that created it.

NM: Totally and I think definitely you can see in certain short film work like there are budgetary constraints to every project really even like huge, massive blockbusters have some kind of budgetary constraint that they're working within. But at the same time, I think what comes through most palpably is the urgency of what the story that's being told is and the intentionality and care behind the choices that were made to tell that story. So you can do, you know, like, you can have the biggest budget in the world but then have none of that intentionality or care. And the final product is not going to resonate with audiences in the same kind of way. And I mean, on that note, how have you found that different audiences have responded to Waking Hour because I know that from my response as a trans woman was definitely particular and I don't feel like necessarily, I was very curious about whether you've gotten responses from cis audiences, from other trans people, what have their responses been in general?

CC: It's interesting because I don't think that I've, you know, been in screening spaces that were segregated, right, so it's typically been trans people and cis people watching at the same time, but I have noticed that in different places, the humor is received differently, like there's times in certain audiences where it's quiet, it is quiet in the audience. This is a serious film, right? This is drama.

NM: Right. And then there's other audiences where it's been a lot of laughter and more laughter than I even expected. And, so that's been interesting to witness. But I think what I can point to is the people who've come up to me, the people who've reached out to me individually and kind of hearing their reflections, and I think that for trans people, and particularly trans women, young trans women, this is a story that they can relate to. And there's a there's an element of being seen and picking up on some of the little nuances. And then for cis people, I think the difference is that there is often an element of shock. That this is a reality for us. Whereas trans people are like, oh, yeah, like this is what happened. You know, that makes sense, right, this feels true. For cis people, there's this element of having a really true educational experience. So I'm really glad that it's able to reach people in different ways.

CC: Yeah, and I mean, I think that, I mean, it's definitely very valid to point out, like you were saying that the audience is reviewing this film, it's gonna be a mixture of people in every context. But it is fascinating to think about the ways in which, I mean I really want to get as a society to a place where cis people are having the same kind of reactions to trans characters that we've had to have, like same kinds of relationships with trans characters that we've had with cis characters for years, where, when I was growing up, I had, you know, these characters that I identified with in film and media in all kinds of things. And because I didn't see myself, I was able to find parallels in these people who, like, in looking back at it and like, well yeah, there's probably not too much, I don't probably have too much in common with Xena Warrior Princess at the same time, do I?

NM: Well, I mean, it was important for me to tell a story about a woman's experience and for it to be an experience that anybody really could relate to when it comes to intimacy and consent. So yes, disclosures is a big part of Waking Hour. But when I was writing it, that's not what the story was necessarily about, it was more about consent and intimacy and the vulnerabilities of those topics. And so those to me feel very accessible universal themes, and I have had people share how meaningful a story like that can be for them.

CC: Yeah, and I mean, that's an extremely fascinating point because the experience of negotiating consent in a sexual or romantic exchange is pretty universal. And that's a something that, speaks to, femininity in all of its forms, but also just personhood. And, like, for example, relationships between two gay male identified folks have similar, push and pull back and forth kind of dynamics, as far as consent and boundaries and like what feels safe and what feels comfortable for people. And that's, I think, really palpable in the film itself too. It comes from a really, like, keenly observed sense of those dynamics, and whether that's from your own actual life or just from observation or like it just it translated extremely well in the shore itself.

NM: Thank you, I'm so glad. And I think that also speaks to the excellent performances from Raphael and Mandisa who played Isaac and the driver. Because, when we were preparing to shoot and on set, like I kept telling them like, this is your story too, like, this is a waking hour for everybody in the story. All three of us the next day are gonna be thinking about this.

CC: Right.

NM: And so they're grappling with issues of consent and intimacy as well, including Mandisa, right? Like she's inserted into this thing in her car. So I think it was important for me to show that, when we experience things it's rarely in isolation. It's almost always in relation to other people.

CC: And that's fascinating too, because that's a choice and I don't think that every filmmaker would have made the choice to take the camera into the front seat and show the Lyft driver who's inadvertently part of this extremely charged situation. And the choice to do that is, to me a reflection of, a cinematic voice that is constantly attuned to those relational sort of dynamics, as they touch one another's lives, you know, no matter how big or small, and that, to me honestly feels like a hallmark that calls back to the work you were describing in the beginning where it's, an awareness of interpersonal dynamics, but it's an awareness of also like larger structural forces that work.

NM: Yeah, that was a lot of the work that I did in the counseling room was how to negotiate these situations and how to communicate with people and when to intervene how to speak up and when to just get out and in safety planning, right, a lot of the frameworks from my counseling work with survivors of intimate partner violence show up in Waking Hour, because about consent and it's about intimacy and vulnerability, and safety ultimately.

CC: Totally, and the thing is, too, it's like, I think it's really worth all of us having this awareness of the fact that if we are all sort of at work to break down these larger systemic issues, we have to be conscious of the fact that sometimes most of the time, these larger oppressions are being enacted on us via the vehicle of an individual person. So people have individual responsibility within these larger systems, but also, there's both like, personal responsibility and acknowledgement of the larger factor for us, whether that be like toxic masculinity or racism or any, you know, of these larger entities.

NM: Well, thank you for that analysis.

CC: I don't know, it was making me sort of go down this like train of thought, I'm like, yeah, and actually it sparked a lot of thought for me. So I appreciate the film for doing that. One thing I mean, the biggest takeaway from me, for me personally from the film was, again, similarly to the feeling that I had from watching River Gallo's Ponyboi, which is the subject of the episode of this podcast. I found it really fascinating to have this story of a character who is being perceived as sexually desirable, within a world that frames who she is as not desirable or as the quality of desire being super unknown or like just there's no framework for analyzing desirability. And that's an experience that I found very relatable as a trans person because I think that there's a lot of misunderstanding of that in the cis world, to be completely honest.

NM: Oh yes, I think from my personal life, I think there's times where cis people, especially who maybe don't know me, or people who've known me for a long time, and haven't seen me very much in the present day are like surprised that people find me desirable.

CC: Right.

NM: And I'm just like, what is that? What is that surprise? 'Cause it's so not, I've always known, right?

CC: And that's a consistent thread that I've heard from talking to, I mean, and seen evidence of, considerable evidence of in my actual life, for every trans person around me is that like, there is a ton of this real desire that exists out there in the world that's directed at trans people. And yet, there's no cultural understanding of that desire. And so those are the conditions that create by violence a lot of the time because–

NM: Yeah, the desire is forced to be clandestine, right? It's forced to be stigmatized.

CC: Yeah.

NM: And so it does lead to violence in the end, exactly, yeah.

CC: But I do you think that sort of coming back around to the role that art and creators of film and all kinds of arts have to play in changing that conversation, I think that like the fact that those kinds of stories, those are what trans and gender variant people from under the entire umbrella, are choosing, those are the stories that they're choosing to tell, that we're choosing to tell is meaningful because I do think it's hopefully something that can lead us to a world that does understand better and does have a better conception of how to value us.

NM: Yeah, I agree.

CC: I mean, was that something that was sort of in your mind while you were making Waking Hour or was that just a sort of like a byproduct?

NM: Not in the writing, no, the story just kind of came after rattling around in my brain for like a year, and that was the story that needed to come out. But when doing test shots in the month leading up to the shoot with Aja, the DP, we did discuss, portraying me as beautiful because, right, you can make different choices and not prioritize somebody's beauty when you are choosing your shots and lighting and in the edit, right? But it was a priority, a, for the character right like this is about a young woman who is attracted to and is attractive to this man and two, for the product, right? I think that it does have power to portray a trans woman as beautiful and desirable. So we did make choices, right, like we found the angles, like we can execute with the lighting, like, it was important to highlight my beauty, which was the conversation we had, which it was part of portraying that character and portraying myself as desirable.

CC: Yeah, yeah, I mean and it's yeah. It's an interesting sort of element of representational responsibility. That is something I sort of wanted to talk about in general. And just as a trans creator, who has at least told one trans-centric story on screen, do you think that you feel that kind of pressure about the representation of trans people in this widespread, large scale way?

NM: Absolutely, absolutely. I mean I'm coming again, I'm coming from work that allowed me to meet several different kinds of people's needs, and to be involved in several different efforts for liberation and for justice, and for safety and so it's been a huge adjustment for me to then have to place myself at the center and focus on myself so much and specifically to focus on my appearance so much and to have my body be the vessel for the work. All of that has been a huge adjustment for me. And I just know that there's so many stories that need to be told. But I'm not the best person to tell those stories, even amongst communities of tans Latinas, right? Everyone has such a particular experience that it doesn't always make sense for me to tell a specific story just because I am Mexican American and I'm a trans Latina like, there's so many little nuances there. And so I would like to be at the point in my film career where I have a structure built that I can just open doors for a whole bunch of people. But I'm still in the stage where I'm having to build up myself in order to build that structure. And I am very much still figuring out how to deal with what it means to do that.

CC: Yeah and, I mean, I do you think that there's this, some of that responsibility is real because, there's just are comparatively so few just in number, representations of our community that come from the authentic perspective. But I also think that every individual person can only really at the end of the day represent themselves. And the stories that they want to tell are only going to be able to come from their specific perspective. So there's a beauty to that specificity too and that's something that's not a bad thing.

NM: I don't know, do you mean from writing or for directing?

CC: Well for anything, really, I mean, it's just like, you come from the perspective of the background that you have and the identity that you have, but you come from your perspective from your lived experiences. And so to narrow it down like that even further is, I think also important and to remember that like, you're bringing to it all the specific character that you bring, not just based on ticking boxes.

NM: Yeah, of course, of course. I'm just thinking about if that idea might be too limiting.

CC: Yeah.

NM: In the nature of this work that we do, because–

CC: Because it just needs to be built too and I also think that in the lieu of a million different voices all speaking at once, we need to have things that stand in to represent other things, too.

NM: Yeah, like it shouldn't be that Latinx filmmakers can only work on Latinx stories and black directors can only direct black stories. That should not be the case. However, the perspective does matter.

CC: Yeah.

NM: So I think that's the like, the pickering and the nitty gritty that people need to pay attention to, and I think, it's what is happening. But we need to keep it up. We need to keep pushing to really work out what it means to be responsible with our perspective.

CC: Yeah and I just think that is really the case for everyone involved in anything, film production-wise creatively, in general. There has to be sort of, and I think that there's a growing consciousness of the responsibility that exists inherently in that. When you're putting something out into the world, you are creating something that's gonna touch someone's life in one way or another, and that's responsibility, you know?

NM: Absolutely.

With ripple effects. Yeah, it's such a privilege to be able to make film and television as the most expensive form of art, no matter how hard it is to get a single minute of film made the fact that for those of us who are able to get there, it means that there is a platform that we had access to, to be able to do that work. So yes, there is a power and a responsibility that comes with creating film and television.

CC: And we're gonna probably end up wrapping up in a little bit, but the final sort of vein I wanted to chat about, I guess, is to go over your experience on the set of Disclosure, which we recently just we're speaking with Ava Benjamin Shorr, who's the DP of Disclosure, and I know you were also onset as a production fellow?

NM: Yes.

CC: So what was your experience like on that set? And I mean, I just wanna send it off on a note about sort of, with that mindset about intentionality and everything that we've been talking about in terms of responsibility from what I was talking about with Ava, it seems as though that was a set philosophy that was being tapped into on that set.

NM: Sorry, so, what's the question?

CC: So I just was hoping to hear more about your experience on the set of Disclosure. I just got very long winded there.

NM: No, I mean, there's so much to discuss and I know you're not gonna get to probably everything you had hoped to discuss.

CC: We could just keep going and going. Truly, I love talking to you, so.

NM: I know it's really, really nice to be able to engage in this type of conversation. Okay, I was on set in 2018 for Disclosure. And the only time I had been on set before that was my own set for Waking Hour and a another Indie crowdfunded micro-budget short film called Sprint by Nana Duffuor in a nail salon in Oakland. So, I had never been on a set of this magnitude. I had to learn how to use the walkie system and how everything worked. And for me, that experience set the standard. I'm so lucky that I'm coming into the industry at a time when I don't have to work thousands of hours gaining experience on sets with angry old white men who are yelling at everybody and abuse people in their trailers. I'm so lucky that that is not the context within which I have built my experience and my skill set. So instead, I got to learn on a set with trans people in leadership, trans people all around, and a set that valued, kindness, patience, humility, and the goal was for everybody to be respected on set. So something that I am remembering from that experience is that Sam Fader, the director, he genuinely was happy to hear from us, from everybody. And I'm realizing that on another set, I maybe could have been asked to not come back the next day for being so vocal or for being too to present. I think the traditional models of filmmaking ask so many people working on set to make themselves as small as possible. And that was not the case on the set of Disclosure. So that's another thing that I'm taking as a goal for my work is that everybody has something valuable to contribute, and not just necessarily in the function that you designated for them. So, yes, sometimes there's not always time for it. Sometimes you need to look to a specific person with expertise, but sometimes the PA has something to say.

CC: Totally.

NM: That is worthwhile because that PA maybe has directed on on another set, right? That PA is coming in with a lifetime of personal professional experience. So it's important to listen to everybody on the set and I'm so grateful that I got to witness that on the set of Disclosure.

CC: That sounds, amazing honestly. And I really think that it's the kind of, those are the kind of lessons that I really hope get taken into more sets in the future, so that that's not sort of the anomaly. That's not the one off, that's sort of the standard. And then any other way of handling those things that's less respectful of people's time and experience. Those are the models that get sort of phased out. I think that it's really worth knowing that, no matter what someone's CV says, in terms of their experience, it doesn't mean that they don't have insights and perspective and vision and all kinds of things that are extremely important to bring to a film set or to really any professional environment. Which is why I mean, when people talk about, like, oh, well, we would have hired X or Y person to do X or Y thing, but they didn't have the experience. You can train people how to do specific tasks, but you can't train someone to have perspective and to have like life experience and to have empathy and to have the ability to relate to other people, those things can't be trained. So, I think that, you know, I hope that there are ways every industry sort of becomes better at incorporating more people without maybe on-paper experience, but with lots to offer.

NM: Yeah, absolutely. And this is something I shared, as part of when I spoke about the my experience on Disclosure, I said that these values need to be built into the production budgets, they need to be built into the schedules. They need to be built into the hiring practices, so that you have space to train people. So you have space to build bridges. So that you have the time and resources to have something like a fellowship. So that okay, you know what, we couldn't find a gaffer that has this experience, but we can hire a fellow, right, to work with that gaffer. There are ways to prioritize these values and it just takes commitment to them.

CC: Yeah it just really you have to take action and make choices that support those values. If those are your standard values, there are actionable ways to support them. People need to make it more clear in their actions, you know.

NM: Absolutely, yeah.

CC: I think we can go for one final question 'cause I could truly ask you 5 million more questions. There's so much to talk about. But I wanted to sort of finish up with just on a personal note, it's a crazy time. There's a lot going on, obviously, a lot of really, a lot of momentum in some really positive ways toward causes that have needed widespread attention for years. And at the same time, a lot of disorganization, pain, discomfort, death even. There's a lot going on that's extremely negative as well and how have you been sort of navigating your own space and mental health and just kind of keeping your head above water lately?

NM: I feel like I got a little bit of a head start on quarantine nothing to add, because of my work on this series that's gonna be coming out next year.

CC: Drop the name of that series again, just so y'all can get it,

NM: It's called Generation, it's gonna be on HBO Max. I don't have too much to share 'cause I don't know when everything will go up in the air. But I'm so excited about that series and I can't wait for us to be back on set and I'll be probably acting in that series. But because of the timing of that, I was already like at home, I was already spending a lot of time on my own and then the quarantine started and then the uprising I found myself very isolated. And so I had to find ways to reconnect. So that's been really grounding for me is to be back in touch with people from those circles that I used to frequent. I have offered to do translation work, to translate Black Lives Matter movement materials into Spanish. I've just been having more conversations with people doing organizing work and trying to write, trying to get a writing group together, like trying to stay grounded in the work, donating, spreading educational resources, all of that has made me feel less isolated. And like I am still able to contribute to the movement and organizing that people are doing around. This is really challenging issues. And I just have to take it day by day, I take walks, I take baths, I eat salad, I drink water. And I'm writing and I'm allowing myself to write freely and journaling fashion while somehow trying to make myself produce, actual shareable pieces, but it's really day by day. And the key for me has been reconnecting with people.

CC: Yeah, I mean and I think that that's as much as we're all separate for the most part right now. There has been so much that has, not to end on a super cheesy note, but there has been so much that has connected like all of us to each other and there's so many ways I think that people are realizing how much all of our futures are intrinsically linked in this way, which is really powerful and beautiful too. So amongst all this pain, maybe and hopefully out of all of this pain can come something that feels more interconnected and more unified than ever, hopefully.

NM: Yeah, I think that this is a moment that has mobilized a lot of people and I am so inspired and I'm so proud of people who are resisting oppressive forces in so many places in the world, and in so many different ways, and I support them. And I am committed to engaging in that support in tangible ways in the moment and I'm still building towards a long term vision where my work creatively, somehow takes part in that as well.

CC: Yeah, well, that's I mean, and that's a great vision to build toward for sure.

NM: Yeah, you know, ambitious.

CC: Yeah, you gotta have somewhere to shoot for, you know.

NM: Yes.

CC: So I think we're gonna wrap up. But thank you so, so, so much. This was such a, just like, hearing you speak about all of everything we covered was so wonderful. Thank you so, so, so much.

NM: Thank you, thank you so much for inviting me and for sharing all your thoughts, you are brilliant. And I'm always happy to talk about these types of topics.