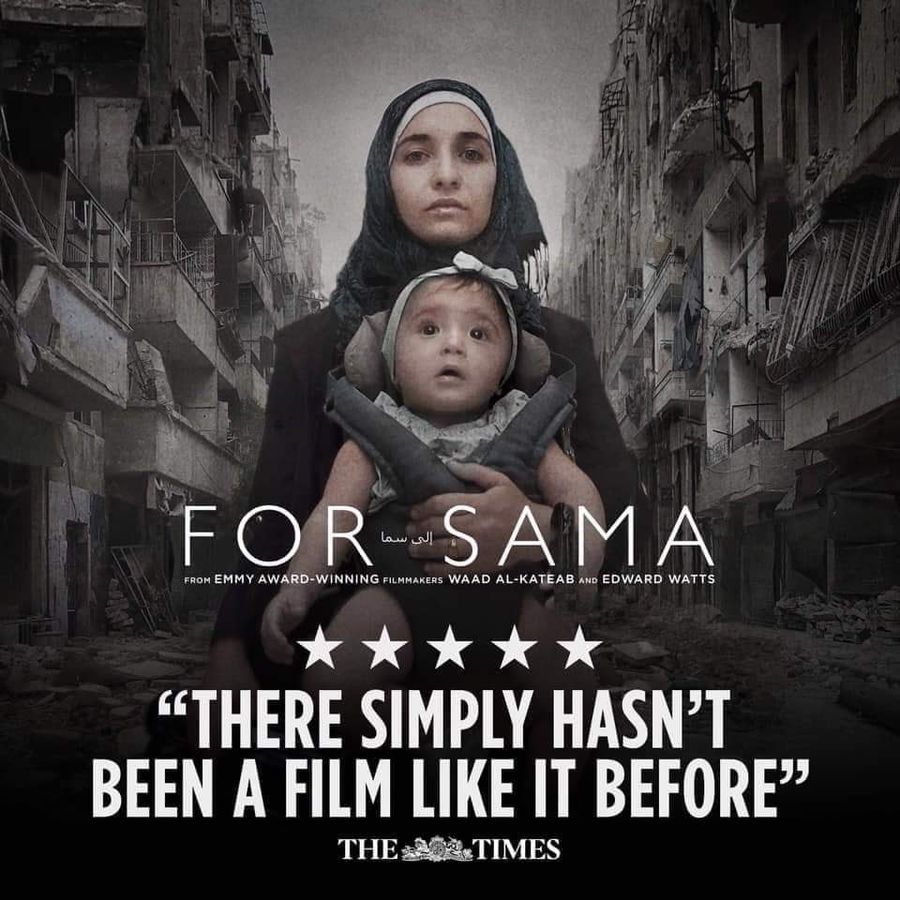

For Sama is the first film to document the Syrian conflict from the perspective of a woman.

Behind the film as a director and as the film's subject is Waad al-Kateab. Waad is a Syrian filmmaker who has won Emmys for her coverage of the Syrian war from her home of the rebel-held town of Aleppo. For Sama, which won the Best Documentary at this year's Cannes Film Festival, is a compilation of five years worth of recordings that document her journey with starting a family.

In this episode of the FTW podcast, Dana Ballout interviews Waad about For Sama and how Waad's life has changed since the completion of the film. Dana is a journalist who spent years covering the Syrian war and the refugee crisis for The Wall Street Journal. With their close personal connections to Syria, Dana and Waad's conversation become a special exploration of the crisis in the country, what it's like to be a woman in the midst of the violence, and how the film can help shed a new light on the refugee crisis.

You can now watch the film in its entirety on FRONTLINE PBS.

Listen in to the podcast by hitting the Play button above, or by clicking on this Soundcloud link! Keep scrolling for the full transcript.

Production Sound & Editor: Jasmine Chen

Waad al-Kateab

Waad al-Kateab was a marketing student at the University of Aleppo when protests against the Assad regime swept the country in 2011. Like many hundreds of her fellow Syrians, she became a citizen journalist determined to document the horrors of the war. She stayed through the devastating siege — documenting the terrible loss of life and producing some of the most memorable images of the six-year conflict. Reports she made for Channel 4 News on the conflict became the most watched pieces on the UK news program. They received almost half a billion views online and won 24 awards — including the 2016 International Emmy for breaking news coverage. When she and her family were evacuated from Aleppo in December 2016 she managed to get all her footage out, and created the documentary For Sama (Mountainfilm 2019) to tell her own story.

Dana Ballout

Dana is a Lebanese-American documentary producer and podcaster based between the US and Lebanon. She's currently a producer for Muck Media, an LA-based award winning production company that specializes in investigative documentaries and character-driven series. Dana is also a producer and editor on Kerning Cultures, a podcast dissecting the complex narratives around the Middle East.

Before moving into documentary, Dana was a reporter for The Wall Street Journal, covering the Syrian war and its resulting refugee crisis. Over the last decade she has worked with organizations that range from the United Nations Development Program, Al Jazeera English and America, Netflix, National Geographic and others.

Chloe Coover: What’s up, world? Welcome to the Free the Work podcast. Free the Work is a talent discovery platform that uploads underrepresented creators and connects them to those who hire in film, TV, and advertising. And now like all respectable organizations in this age of human history, we have a podcast! Come kick back as we chat with some of today’s most influential creatives. Consider this the film school that you never have to pay student loans for and the creative guidance that your horoscope could never give you.

Today’s episode features a conversation between journalist and producer Dana Ballout and Cannes award-winning documentary filmmaker Waad al-Kateab, the director of For Sama, a love letter from a young mother to her daughter. For Sama sees the Syrian War through the eyes of al-Kateab as she documents five years of the uprising in Aleppo all while falling in love, getting married, and giving birth. Tune in as Ballout and al-Kateab discuss the pain, the beauty, and the hope of the ground-breaking feature. We hope you enjoy and thanks for listening.

Dana Ballout: Hi everyone, my name is Dana Ballout. I am a documentary producer, podcast producer and journalist. For Sama is very personal for me because I used to cover the Syrian War for The Wall Street Journal and I remember covering Aleppo and the siege on Aleppo very closely. And speaking to Waad’s husband, Hamza, for quotes on our articles, so watching the film has been an incredible journey and also very, uh, difficult, but also very beautiful. I’m sitting here with Waad in Los Angeles, after being in the Middle East feels surreal. Thank you so much for being here Waad. First of all, I want to ask, how are you? How’s Hamza? How’s Taima? How’s Sama?

Waad al-Kateab: Thank you for asking like we are, uh, fine, good. Thanks for having me. I’m so happy to be with this great podcast. We’ve trying now to adopt with the new life which is total different from what we were before and at the same time, life’s so busy with the film so I’m barely seeing my kids now. Sama and Taima… Sama now she’s four. Taima is two and a half and they go to the nursery and they speak mixed between English and Arabic, so um lovely, nice.

DB: And you’re living where now?

WA: We live now in London. And Hamza is working. I’m working now with the film, so we’ve just… as any normal family all over the world.

DB: Amazing. Waad, I want to go back to the moment where you first picked up a camera and hit record. Do you remember the first time you recorded something?

WA: So the first time twas the third protest I’ve joined in at Aleppo University. The first two I was so shocked about what I’m seeing and I- I can’t remember if I literally like shot or not. I can’t believe that this is the protest happening, so I was like so freezing in my place. But the third one, I feel that like no this is really happening and I need to be part of this, I need not to just participate in this protest, but also I want to play like more than that role, so I picked up my phone which was like so bad at that time and I recorded the first video for me and there was literally a wave of people who’s running to the university, to my college, and they were like chanting against us at…And I remember it was like around 20 second or something, but I was so happy with that video. I’ve looked at that again and again many times later after this. And it was just the feeling that you are documenting part of the history of our life. And twas so important for us because the regime was denying, everything was happening, so capturing any video, any photo, and even like just sound will be so important for all of us.

DB: Yeah. What was your life before that moment?

WA: Uh, before the revolution, I was normal girl as any girl around the world. I have some dreams of where I want to go after I will graduate…uh, what’s my future and how it will be, but unfortunately because Syria before was just so bad place to build your dream because of the authorities and the bad government. I always thought that I will travel out of Syria and start my future out and that’s why I was taking some courses at TKTKTK , German, uh language. And suddenly when the revolution started I felt that, “no, this is only to bring change.” I’m Syrian, I’m so proud that I’m Syrian now. I can be part of that future and I wanted to do it here in Syria.

DB: How did you decide that your role was going to be documenting?

WA: So I’ve never realized THAT, you know like as what I’m doing and especially when that’s circumstances, when you are so busy with everything happening around, you’ve never think about up next, or like after that, so I was just trying to document everything that I’ve seen in my eyes, anything I feel that this could be important for next and without literally like a new, you know, like wh- what’s the plan, why I’m doing this, or how I can, um, make it as a real project. I was trying to just develop my skills and my equipments very slowly as much as I can.

DB: Waad, you know, it must’ve been different for a woman also to be documenting and to be in protests and sometimes it’s different, you probably see a lot more men in these streets and a lot more male journalists and documentarians in Aleppo and in Syria and our culture in general. What was it like as a woman doing that?

WA: So 2013, in January, there was a big meeting for all the citizen journalists and the journalists who are in this part of Aleppo and the district. I walked into that meeting, it was so shocking and so I was so shy because there was 121 man who’s having camera and wants to be like more professional in journal. And I was the only female. And I remember like half of them were like supportive and they want me to be like a part of this. And the other half were like looking at me as, “What’s she doing here? Who’s she? And why she will be in this community?” So it was so strange, you know? But at the same time, like five years after this, when I’ve just spaced out of Aleppo and I went to the first ceremony I was nominated for. It was like so long time between this. And I got the Camera Operator of the Year in a Royal Society of Television in the UK and they said at the introduction of this award that this is the first female ever got this award… and literally I remember just that day back, 121 male journalists, and after five years in different part of the world which should be totally different still like female filmmaking is having a lot of challenging to be in that place and I was like so proud of that award, so happy of being like the first female, more than the award itself. But same time, you know like, it seems like this is a challenging all over the world and female filmmakers just doing their best just to be part of that and they are fighting to be taking their space as they should be. So it was just so shocking that we need to do a lot more to be like in our place.

DB: Yeah, everywhere in the world.

WA: Yeah.

DB: Uh, I saw in one interview that Hamza, your husband, has said in the beginning when you were filming, it was so annoying…

WA: Exactly.

DB: Can you talk to me about how often you would grab the camera? What would you record? And what were things that you didn’t record?

WA: So the first year when I start filming literally everything around, not just Hamza, everyone who was around. They were start to say like, “Waad, stop. What are you doing?” And they can’t understand easily why I’m going into the emergency room to film some of the injured people or the very bad, horror situation. But I couldn’t understand like why I’m going to film just the normal life of that, why I’m filming while we having like dinner or why they were like playing football.

DB: Mhm.

WA: And for them was that makes sense, “this is why.” And with the time they’ve, they were like, “okay, leave her, she’s playing with her camera”. And then all of us, even me, I was so amazed to that situation and I wanted to document this, but I’ve never thought how important is it until like all of us, we lost one of the first friends who were so close for us. His name is TKTKTK. And we were just living together for this sixth month and I’ve turned a lot of normal life how we were together. And suddenly we lost him in one second. And the night after he was killed we were all sitting together; I was showing them some of this material. And literally all of us at that time we realized how our life is so important to be like saved and documented. And since that time, none of them like tell me like, “Stop” or “Don’t film this.” Even if it’s the something like funny they don’t want even to share it outside. And after that they were coming to me, for example, four AM in the morning, knocking on my door, like, “Waad, come come come, we are playing like play card” for example, “Come film us.” It’s became like more giving that understanding that this is life could be ended at any moment and just documenting this will save this experience forever.

DB: Yeah. Amazing. What did you not record? What are times that you couldn’t pick up a camera?

WA: I don’t think there is anything.

DB: That’s great.

WA: I think if my fellow director, Edward, here, he would say that because he always like fighting me to answer this question that, “no no there’s nothing she did TKTKTK.”

DB: Yeah.

WA: One of these things that she always mentioned it was so funny for him. It was me cooking TKTKTK for more than three hours like from the whole process of that.

DB: What were you making?

WA: Sheik 'al Mishee

DB: Sheik 'al Mishee, I love this! It’s uh eggplant with ground beef. Ugh, I love it with the cinnamon…the chicken. You started off recording with your phone?

WA: Yeah.

DB: How did your technology then progress? How did you get a camera? How did you move up? And how did you also keep all of the footage?

WA: So, the first early days when I have just my phone, anything I can see it’s important, I captured, but it wasn’t a lot of things-

DB: Mhm.

WA: like what I’ve done before, after, sorry. But then the first secret camera I had was a pen where there’s a camera and I filmed one of the protests in the university. And then one of my friends who knew that I’m filming a lot now, he said I have like a small camera, handycam Sony, where you can use it but it’s not very professional but also it’s small so you can even hide it in your stuff. And I got that camera from him. I remember I had around seven bags, tktktk bags, and I make in all of this bags, a hole for the lens to be like out. And I took it with me for around like three to four months at Aleppo University and it was so strange experience and so scary at the same time because if the regime or any of the forces or any of the Pro-TKTKTK students saw that I would be like killed or listed. And I’ve never have any courage to take it out from my bag until the big demonstration at Aleppo University which you’ve seen in For Sama. There were like thousands of student who are protesting and the UN convoy were at the university so I felt like, “I don’t care. Whatever will happen, will happen. I need to take this camera out now and film.”

DB: Mhm.

WA: And I got that great day, I filmed a lot of things until like the battery of the camera was dead and literally that time was so amazing feeling. It’s a first time I can like take my camera out and film and some of the student and some of my friends, they were like, “Are you crazy?” like “What are you doing?” and you will see that in For Sama like this big demonstration, it means everything for us and I felt it worth everything that happened and I just like recorded. Two, three months after this when I moved to this part of Aleppo where this area was out of the regime control so you can like do freely what you want, I got my first camera from someone off the local channels and I start just like trying to learn how to do the news report, the very classic ones-

DB: Mhm.

WA: And with the time I start using this with the more like free and unplanned situation that I want to film everything I’ve seen, I want to do everything I can. And every two years or something, after this camera was totally out of service, I got another one on the first anniversary of my wedding, Hamza gifted me.

DB: That was your wedding gift?

WA: Yeah.

DB: Aww, that’s so sweet. So much of For Sama happens under siege, when Aleppo is under siege?

WA: Yeah.

DB: A lot of people don’t know what it means to live under siege, can you talk to me a little bit about what that life is like and what would it actually means?

WA: So, I will tell you, of course, but I really encourage people to see that to understand-

DB: Yeah.

WA: Like whatever I would describe now in my words, but just to see For Sama as this experience I’ve think people will understand more than any other words they could read or hear it. But just to live in that situation when you don’t know when that will be end, this is the awful things, we knew that now that we are under siege, we knew that everything we have could be finished because we are eating these things, we are using this material which we have and we don’t know if there’s anything where we can replace these things…uh, we knew that all the vegetables, fruit, anything fresh, suddenly disappear, and you feel that it’s okay because we have like rice, pasta, and the other stuff when you can restore, but when you find out that all this restore is destroyed because of the, more like animals, animals?-

DB: Mhm, mhm-

WA: What’s it called?

DB: Like little bugs or flat-

WA: Exactly!

DB: Yeah.

WA: But also you need to eat it anyway cause you don’t have other choice and you feel like okay I’m not starving now, but literally after one week you can feel your body how it starts to miss this fruit or vegetables. Everything is really good for the human having like body. And one of the things which happened in the siege, like Sama was around seven and eight months, and I know that as a mom, as a young mom, I’m trying just to do my best for this children, I know that the only thing she can eat now or should drink, is milk. And I couldn’t provide her with this because of my situation and my emotion and the only milk we have was expired, so I was like, “What should I do now for this?” And I know this is bad to give it to her, but I have no other option. So we give her that milk and she was for two weeks, so sick, she couldn’t get enough of this milk, she couldn’t get any of the other food, even the rice or whatever, and after this two weeks, she started to drink some of this milk normally as it’s okay, but you can’t see like a lot of- a lot of other affection for her because of that milk. But as a child she can’t understand that the only problem was she’s so sick like this is the milk cause the only thing she knows is the milk and twas you just don’t know what to do, you don’t have other option, you need just to adopt with this situation. And you know that you are doing wrong, but there’s no other option to do this. And then you look farther than yourself and you’re any as a one person. Look at the other things like the hospital, the supplies, I don’t know if these people has enough and you don’t know how long they have. They can like TKTKTK these things. And just so scary because you can’t know what next and you can’t know if that’s okay or not. Then you can hear the bombing and the attacks which make all of this more struggling to be solved. And it’s literally so terrifying to think about, I don’t know if I will be alive or not and if I was alive there’s a lot of things to take care of more than just what I want to eat or what I want to do. Just not good life for anyone.

DB: Yeah. There are a few scenes in the movie that I want to talk about. One of them is when you first give birth to Sama and you say in that moment you were crying and when you saw her being born, all you could think of was all of the people that have died. Can you take me back to that moment and what you were feeling when you gave birth to your first daughter?

WA: The moment when I give birth to Sama, so during being pregnant of Sama, there was a lot of mixed feeling between how happy I am and how I am so ready to that moment when I brought my first child. As young mom, my first baby and also really nice moments of having this, to the point that sometimes I was forget where I am this world. And then you have a lot of different feeling of how scary I was or how this situation could be like worse in the coming days and you just struggle between this two feelings to keep happiness over everything. And then I was terrifying that this life could be not even see the light at the end of this pregnancy. And when that happened, you know all this fears and worries which you are trying to hide during the nine-month of being pregnant. I cried and cried and cried as I don’t care now about anything in this world, this baby lived and I’m alive, and I can see her face. And I remember all the people who were with us from the early days of the revolution and we lost them and I wish they could seen that. I wish they were around us in that situation. And I know that they can’t be back, but I know that now I have a new baby, I brought alive to this crazy world where just everyone around is just dying and it’s unbelievable feeling and so far I can feel it exactly as it was. And I remember this was saw in the film when I was just crying and crying. Sama was reacting to this crying and she was crying in very funny way and everyone around us was just crying and trying to, “Waad, come back to us. It’s fine. Everything is okay.”

DB: One of the beautiful parts is that I feel like Sama is the baby of the whole neighborhood.

WA: Yeah.

DB: You know? Everyone is like, “So and so is taking Sama. Here is Sama with someone.” And it’s these moments of lightness in the film that make it so special. And one of those is the humor. I mean, obviously there’s a lot of destruction and death and it can be a difficult film to watch, but there were points where I was laughing so much because there is something also that the Syrians are known for. They have this light sense of humor in the face of such darkness.

WA: Yeah.

DB: And so much of that came out in the film and I think one time your friend who’s the mom was laughing because her young daughter peed in the bed out of fear which is so sad but also she was laughing. And I wonder why, were you purposefully filming like those kind of light moments?

WA: It’s so normal, you know, to feel this all over the place around you and very like bad situation and very good and nice moments. But for example, when Afara was telling me this, she was laughing not because Nya was pee on this, but because she had high expectation of her husband bringing her like coffee while the opposite was happening, so, you know, we have a lot of optimistic all the time and how this situation is so bad and we keep being like have hope, we keep having like nice moments and high expectation and everything will be fine even in the most darkest moments. And I don’t think this is just Syrian sense of humor-

DB: Yeah.

WA: I think this is every human being who has a very tough situation and they want just to fight this scary in a very good way. We were just trying to create that hope even if it wasn’t existent at all and this is what we have so far-

DB: Yeah.

WA: Until now when you’ve seen all this situation now in Syria. It’s so bad. People still need to live, still need to feel that whatever the situation we can see the positive of this or we can see light coming from so far and this is where we need to catch it and still like go to that way and you can see like this in the film in many, many places.

DB: And with the, um, TKTKTK

WA: Yeah.

DB: Yeah. Speaking of capturing some light, I wanted to talk about Hamza a little bit, your husband, and his role in the film. What would you say was his role?

WA: So, okay, I can speak very neutral about this cause I love him! And he’s my hero. Hamza as a person, he was nice guy. He’s so optimistic like a lot even to some point where you could get angry because he’s too optimistic and he’s so cool with everything that’s happening. So even if the situation was so bad everyone is so stressed, Hamza the only who can walk in the corridor and singing as like there’s nothing happening around and I felt in that time when I was there sometimes real annoying from this because like, “Hamza, you can’t be cool all the time.” I’m really like scary or I’m really like angry. And he was like, this place where there was more than one hundred person of the stuff in the hospital, if I am the one who is managing everything was a bit stressed or scared or angry, that’s will affect everyone all over the place, so I need to be that even if I wasn’t literally in my heart like this. But this is a big responsibility and I need to be in that place for all of these people. And you can see that exactly because if you ask all the people who were around us in the hospital, and the siege specifically, you can see the only way why everyone was so calm and strong was because of Hamza. And you feel that sometimes even if he was not good, you can feel that, “I can be the one whose better and stronger.” And this is things, it’s not things you want to do, suddenly you find yourself that, “I’m stronger and I want to stand with this person who’s always standing with me.” So just like relationship, it’s a great community which was all over the hospital itself, the Aleppo, this city, like Samar Afara and their kids, Ahmad, many many people… I don’t wanna name all of the people who I know in the film. But it’s just human being who they can be all together against all these fears.

DB: Yeah. There’s so much love in this movie as well which is so wonderful. It’s the love of community and the love between you and Hamza as well and the love for Sama, obviously, and Taima.

WA: And for Aleppo.

DB: As- and for Aleppo, the city. I wanted to ask you, Waad, sometimes living through that is very very difficult and also leaving must’ve been also so difficult. Sometimes I think mental health where we come from is not something we talk about much, how are you? How do you deal with being away and dealing with what you’ve seen and been through?

WA: So, like unfortunately, so far there’s no time to dilute this and the process everything we’ve went through. The first fact that what happened and what we went through still happening so I can’t really now have any kind of sense that this is could be solved as mental health or as like a going to therapist or anything cause this situation is so bad. We need to at least feel that there is one step of accountability, one step of like justice, or least everything we’ve went through is over now like how we go to someone to speak about that and find a way of how we can understand this if the nation aircraft still bombing the areas where people still living. It’s not just about Waad or Hamza or my daughters, it’s about Syrians in all over the world. There’s a lot of big problems, there’s no innocence of the solution to this, and the only way to challenge this and fight this is to keep doing something for these people and for me, the film now is one of these tools which I’m trying to find a way to create a hope again for the Syrian people, for all of us, for me personally that I’ve done something, it will stand against that propaganda. It will stand against how people in the West see these refugees or see these people as they are just coming to take their place and their country while the opposite is right. People were fighting to stay in their homes and they became refugees and out of their control. And just waking up everyday, hoping that a comfortability will happen, so to bring Syria back to the news now and to find a way of make people in solidarity with the people who’s still suffering in Syria. That’s makes me feel that it’s not about how we will recover from this-

DB: Mhm.

WA: but it’s more about how we can keep going and never give up.

DB: I want to take some time to talk about the film came to be, so you had all of this footage, how did that turn into the film that we see today?

WA: So I filmed for five years and I’ve never thought about a plan of how I will use this material. I worked in the news for a while and I tried to do some short documentaries, but I’ve never though about using my personal stuff which I was filming, in case I didn’t make it out to do a feature film. But then when I was shocked when I was out of Aleppo and I’m survivor now and I need to do something, so I went to Channel 4 News, where I was working before, and I showed them some of this material. And they were so shocked because we’ve never had a chance to speak more about what I was doing inside. We were just dealing with small, short news and that’s it. There’s no time even to tell them that, so we had the chance- so let’s do a bigger movie as something could be really giving to people and their understanding of that experience and they introduced me to Edward Watts, my fellow director now. And we start working together. Tooks us two years to set up the film as you’ve seen as For Sama and it was just a great experience for me to know more about this film.

DB: How long did the editing process take?

WA: It took us two years until we like submit the film and we felt like we are both satisfied on the story and how it presented to the people.

DB: You narrate the film-

WA: Yeah.

DB: How did that narration happen? How much time did it take you to write it? How many takes did you do?

WA: So it’s about how we will do the film?

DB: Mhm.

WA: We had like thousands of ideas because the archive is so huge so we had a story of my personal life. It’s the story of the hospital itself, the story of many families who I’ve followed during the five years, the story of the city and a lot of other elements happening. So we were struggling of how we would tell the story in the best way. So after awhile we start feeling that it could be part of a personal and through this personal story, I can tell the story of everything was happening around. One of the ideas which we tried was to be me interviewed inside the frame and we did one interview for five days. I’ve spoke about everything we went through, personally and in general. And that’s help us personally to build the line of the film itself. But then we felt that no need for me to be presenting in the film. In that way, as an interview, but more about direct way through like the voiceover when I can tell people lots of things they can’t see in the film, but how my feeling was in that situation. So we start like writing from the first- even before we do the interview and then develop through this years. It was like an open draft all the time, just again and again and editing again and then changing a huge things and then coming back to something even before out of chaos. And I think a lot of the directors who was hearing this, they can’t understand-

DB: Yeah.

WA: that exactly. But then the alphabet was after we finish the whole film and we sign it off, we feel that we want to be back to push the voiceover forward again and I took two days off when I went just alone with the film and I just watch it and write. Watch and write. And I just wanted to be very honest with the people as much as I can. I literally lived the five years again and again in just two days and then I went back to Ed and share all my thoughts with him and we write it again in the best English way cause I’m not native English speaker so that’s also a lot of challenging during the process. And then we wrote the voiceover and we record it and we added it to the film and then it was different, it was like full, ready.

DB: What was the moment that you knew that this film was going to be seen all over the world or that it was going to make an impact? Do you remember that moment?

WA: We’ve been told a lot during this two years that people is not coming to watch another Syrian film and people is so like numb and tired of that and we were literally believed that. And during the process everything we were thinking about we want the film to be the best thing for us and then we can speak about what the audience will see about this. My first screening at South by Southwest, I was so terrifying. I’ve sit alongside the audience and I was waiting how many people will leave before the film will be finished. And me, Ed, the whole executive producers of the film, everyone from the team who was there, we were shocked that no one left at all and people… like we had a first standing ovation and people just like follow us out and they want speak more. The great thing happened when someone of the audience stand and said, “What can we do?” And that’s give us a lot of feeling that we did it. We did not just to the point that people sit and watch, people want to do something and be involved in this. So far it was amazing received all over the world in different places like TKTKTK to Mexico to Korea to China. It’s so far audience from us, but all of them are engaged the same way exactly so, um, I was so happy and so proud of that and I wish as much as audience can see all over the world that will be amazing.

DB: What about your friends and family?

WA: So Samar Afara and her kids lives now in Turkey and they just went to their first film festival in Turkey where the film is presenting there, so they were introduced to the film and I’m so happy that they will have that experience because of the visa issues and these papers that we couldn’t bring them out to any of these events, so they will try this experience now.

DB: So this film is called For Sama and if you’re going to make a film for Taima, what would it be about?

WA: I don’t know exactly, but my hope about this is we will be when we will be back to Aleppo and I will make it for Taima and I will have both of them showing them Aleppo and where we went and I hope that they will be for free Syria.

DB: I hope so too. Anything else you want to add?

WA: Thank you so much for all of you.

DB: Thank you so much.

WA: Thank you.

Chloe Coover: Thanks for listening. For more of everything Free the Work, go to www.freethework.com .