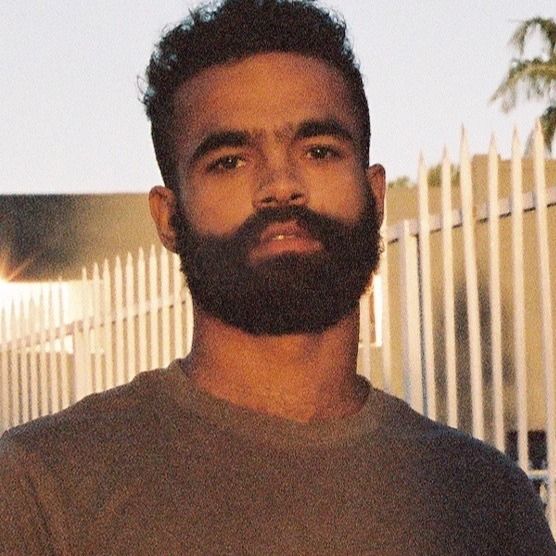

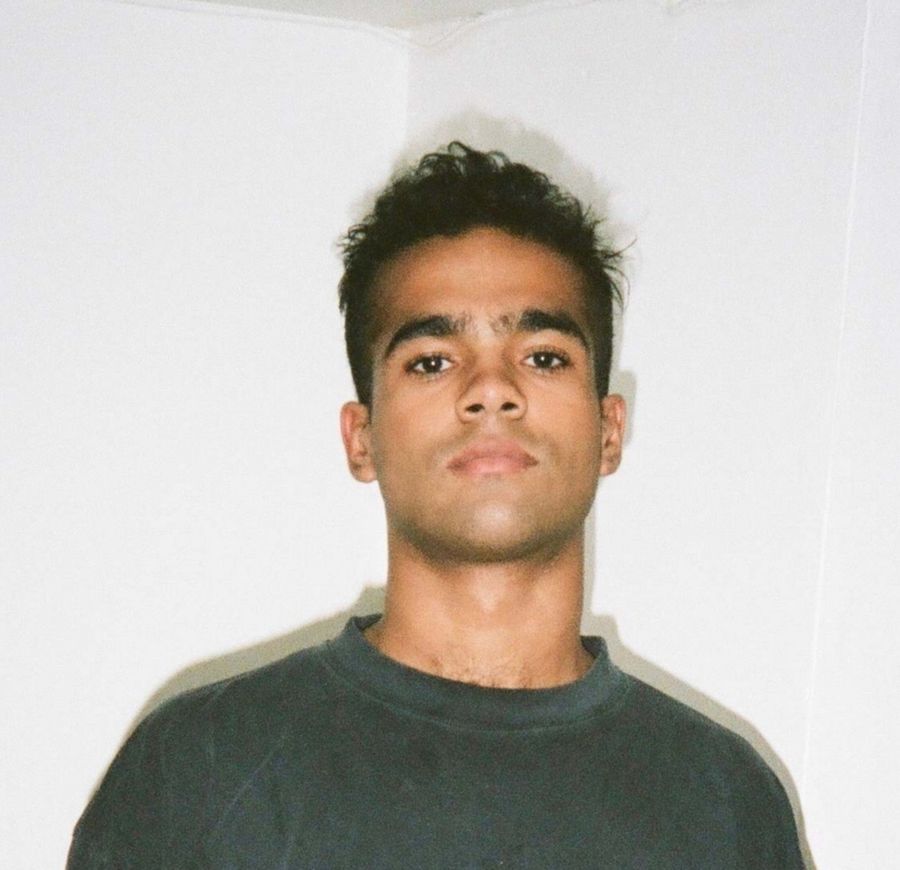

A couple years ago, 17-year-old director Phillip Youmans was working at Morning Call, a beignet stand in New Orleans. He was raising money for a feature film that he would spend the summer before his senior year making with his best friends. That kind of hustle wasn’t unusual for the kid; his life revolved around the movies. He spent his formative years working on film sets that would come into town and attending any screening he could at the local New Orleans Film Festival. Before his high school graduation, he finished said feature: Burning Cane.

Cut to 2019. What once was a student’s simple passion has now become one of the most talked about films of the year. Inspired by Phillip’s upbringing in New Orleans and the Baptist church, Burning Cane tells a cautionary tale of what happens when the rigid teachings of religion are interpreted directly. Spread across a humid summer in the South, the film creates beauty out of the mundane—humanizing a community of alcoholic priests, violent fathers, and imperfect mothers. The film has a clear voice behind it, and it’s a promising one.

Ever since Burning Cane premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival earlier this year, Phillip’s world has completely changed. At age 19, Phillip won the festival’s top accolade, the Founders Award, making him both the youngest and first black director to win the award. The film was picked up by Ava Duvernay’s ARRAY following the festival run, who released the film on Netflix on November 6. Since then, Phillip has directed the short “Nairobi” for Solange Knowles’ creative agency, Saint Heron, received an Independent Spirit Award nomination, and made it onto the 2020 Forbes 30 Under 30 List. And remember those years spent at the New Orleans Film Fest? This year, he returned to the festival, this time with Burning Cane, as a key to the city honoree.

For our interview, he’s back in Louisiana, home for the Thanksgiving holiday to find a moment of calm in the familiar. Here, Phillip reflects on his life-changing year, relearning what a good director is, and finding the strength to free-fall back into instincts despite his new life.

It’s clear you wanted to portray your community in an authentic way, but the film’s from a perspective that’s not necessarily that of a 19-year-old kid. How did you access that ability to write as an entirely different voice within the same world?

Phillip Youmans: When you’re crafting your first feature, the most important thing is to make it something you authentically know about. With Burning Cane, a lot of the stuff that I recognized growing up within the church was the motivation for the film and what drew me to feel like I could give a respectful albeit cautionary depiction of it. Especially when you look at some of the things that have to deal with actually displaying the church service—those kinds of things can very easily dip into caricature and I think approaching that, even though I disagree ideologically, has to be done with respect.

You were the Director, Writer, DP, Editor, Producer, and Executive Producer of this film. Was that hard to balance?

No, I was having a blast with my best friends in the world. That’s indicative of not having a lot of money or resources. People have to wear multiple hats, and that made sure that there was no attitude on set. We were all sweeping the floors of the location after the shoot. We weren’t rigid about even our positions with each other—we were just making art.

You wanted the set to feel like this really vulnerable place with no ego. How did you create that safe space?

As a director, you set the tone. These people were with me because they wanted to be there. They were dedicating their time and so much labor to help me make this film possible. There’s no way I was ever going to give any attitude or talk down to anybody or treat them with anything less than 100% respect.

With Wendell Pierce and your entire cast, you’re dealing with actors who are much older than you, which can be terrifying. Was this a fear you had going into the project?

It was definitely something that I thought about, but it didn’t feel like anything major because none of them enforced a hierarchy on me. When we got on set, the cast was the great equalizer. Wendell, Kaia, Dominique—they’re all such students of their craft. Despite being incredibly accomplished, [Wendell] is actively still trying to search for more, still investigating his process, still developing his process. There was never any point where I felt like I was too small or that my direction wasn’t being respected. In truth, I lucked out. I had a lot of really intelligent actors that got behind the material from the writing, so then when we moved on set, it was just a continuation.

How big was your crew?

Consistently, it was just me and Mose (Producer / 2nd AD / 1st AC / Boom Operator / Grip), maybe 9 out of 17 days. We had 21 days total, 4 days of pick ups. On the church days, we’d have more people, but most of the days we had 3 people. Me, Mose, and Ojo (Producer / Production Designer / 1st AD). It’s still insane to me to think about that.

"This work is important when you have something to say."

You’ve said how you made a bunch of shorts that you felt were bad that allowed you to find your voice for Burning Cane. What wasn’t working on those shorts before your feature?

I had to take film all-around more seriously. I had to make myself more accountable for my work. If I wanted to really make a project that I could stand behind and be proud of, I had to sit through the process, sit through the feedback sessions, sit through the edit, and not get impatient because it’s taking a long time or not clicking.

In a lot of those early films, I was talking about stuff that was thematically relevant to me, but didn’t nearly feel as personal or important for me to speak on. I got to do a lot of visual experimentation, but subsequently, the work wasn’t speaking to anything I wanted to have a full nuanced discussion about. This work is important when you have something to say.

Our generation is doing a lot in terms of breaking down myths about what a good director is. What did this film help you relearn about being a director?

Being a director is not about being an egomaniac. It’s about always thinking about what’s best for the piece and in respect for the people that you’re working with. I learned in the most humble way that people are so much more motivated to run the mile with you when they’re in an environment where they’re fully respected. I don’t think anything productive comes from hostility.

Do you think that our generation has the ability to change what the standard of a good director is?

I think so! Being a good director needs to be synonymous with being a good human or at least being in the pursuit of being a good human. We’re all fallible at the end of the day. It’s important to separate yourself from the process.

In the case of Burning Cane, I wanted to do everything with it. I wrote, directed, shot, edited most of the film, and then at the last leg of the edit, I had to swallow my ego to recognize that I needed to bring an objective voice in to clean this thing up. My first inclination was that I could do it, but then I separated myself from my ego and looked at what was really in the best intentions of the piece. Ruby Kline (Co-Editor) came in. Ruby is a beast—she’s a year under me—and incredible. I wouldn’t have known that if I hadn’t swallowed my ego and said okay, is that in the best intention of the piece? No.

You worked with Wendell Pierce, Benh Zeitlin, Ava DuVernay, and Solange Knowles. When you’re working with these artists that are so established, how do you maintain confidence in your own voice?

For me, a big thing is that they believed in my creative instincts when I was just following my own without inhibitions. These are all outlets and people that I dreamed of working with and I feel like it’s dope that following my creative instincts—falling back on the stuff that really speaks to me—has been more than enough so far. I’m really fortunate and that helps pacify any insecurities or fears that come when working with artists that are so established, so firmly rooted in their perspective and vision.

"Being a good director needs to be synonymous with being a good human or at least being in the pursuit of being a good human."

Along with those people, you’ve been entering these public spaces, like being the center of attention at Tribeca and getting nominated for an Independent Spirit Award. How does it feel to be in this position?

It’s completely surreal. It feels like the Twilight Zone all the time.

How and when did Ava Duvernay and ARRAY come into the picture for you?

It was after the [Tribeca Film] festival. The moment I heard that ARRAY was interested, I became super obsessed. Burning Cane was made in the most grassroots way possible, and ARRAY is about getting the filmmaker out there on a very grassroots level, so I wrote them a letter.

One of the most illuminating experiences I’ve had recently was taking the film and showing it at Spelman College with a rigorously intellectual all Black audience. Burning Cane is a story about Black people for Black people. I wrote a letter to Ava and [Tilane Jones, Vice President] just telling them that my intention with my work was to humanize my community.

In the case of Burning Cane, it’s a bleak story because it’s a cautionary tale about things that religion can foster, but my intention was never to judge any of my characters. It’s clear that ARRAY's intentions were the same: the Black perspective from a strictly humanizing lens. I wrote that in the letter and said, "It would mean the world to have Burning Cane have its home at ARRAY." I left my number on the bottom of the letter, sent it off, and then I got a call from Ava while I was in the school library.

Your next project is about the Black Panther chapter in New Orleans. Where did that idea come from and what can you tell us about it?

That project bloomed from my time with them. I found out about the New Orleans chapter and fell into an internet rabbit hole trying to find everything I could find about them. I met them in person and it reinforced yet added a whole complexity to those figures in my mind. They were emblematic revolutionaries, but in truth, they’re also human beings. With the intention of humanizing, I just want to create a story about the New Orleans chapter that they can be proud of, that our people can be proud of.

The Panthers have been demonized for so long. There’s this whole symphony of Panther films that are going to come out. I know [Ryan] Coogler is going to make a dope one. It’s going to be such a beautiful symphony of promoting the ideals of the Panthers in a way that’s never happened before. It’s just dope to be in that ecosystem honestly.

How do you feel about the prospect of working with professionals outside of just your friends on this next one?

Yo, it’s insane! It’s going to be a much bigger set than I’ve ever dealt with. I just did a music video for an artist named Leslie Odom Jr. That was the first time where I was [solely] the director. I came on set and was just directing. I had dope people help me realize the vision.It was easily the most stress-free situation ever. With that next film, I want to pay full attention to my actors. I love shooting—thus far I’ve shot everything that I’ve done—but as independent filmmakers, a lot of that comes out of necessity. I do have to recognize that there is a certain mindset there and it is important to be able to recognize when it’s important to take on less roles for the best intentions of the project.

You finished Burning Cane, then directed a short on Jon Batiste, another music video, and now you’re moving on to direct another feature. Do you feel like you need a moment to reflect?

Lately I’ve been taking on pretty much any project I can get my hands on because I like making things. At a certain point, I think I have to consider what my true goal within the medium is. What’s my pivotal, essential goal? Then always make sure that’s at the forefront, no matter how awesome and illuminating and formative all these other projects can and have been. I have to remember to slow down the outside stuff and focus on my next baby.

What’s the biggest piece of advice you can give to other directors just starting out?

We connect to personal stories. [With] Burning Cane, I grew up in the Baptist church, I grew up under that rigid Protestant air. There’s no rhyme or reason why I should’ve been this fortunate with Burning Cane. The only thing I can fall back on is: I was trusting my instincts, really falling back into my creative voice, and that is always enough.

It’s dangerous to use what happened to me as a direct case study because there were a ton of other factors. We were super fortunate in how the community came together. It taught me that if people know how connected you are to a project, their emotional investment amplifies to an entirely different degree. People are so much more into the idea of helping you build this whole thing if they know this holds an incredible emotional significance to you.

It may not always be a pretty picture or an easy thing to digest, but as long as it’s always coming from an honest perspective, it will connect.