Living in the digital age comes with countless perks: you can make a film on your iPhone, your laptop, and even your car’s rear view camera. Yet, analog film has actually made a huge comeback in all formats, in spite of a boom in digital technology. For example, in regards to music videos, three of the five Grammy nominees for music video in 2020 were shot on film, and the winner was also shot on film. Two recent features from directors Alan Yang and Rashaad Ernesto Green were brought to life through film as well.

With the resurgence of analog film, it’s time to get real about what it really entails in the production process and why filmmakers consistently choose it over digital. FTW has teamed up with Kodak’s Global Managing Director of Motion Picture and Entertainment Vanessa Bendetti, music video producer Tara Razavi (Happy Place,Inc. ), DP Chayse Irvin (BlacKkKlansman, Beyoncé’s Lemonade), DP Charlotte Bruus Christensen (A Quiet Place, Molly’s Game), and music video director Cara Stricker (Kelsey Lu’s “Due West,” i-D’s The A-Z of Aaliyah) in order to debunk all myths about analog film and empower the next generation of filmmakers to consider analog film as a viable option.

And if this article leaves you itching to jump into experimenting with film, check out our article with Echo Park Film Center that breaks down the technical aspects of shooting and processing different types of film.

“We shot a lot of Tigertail on 16mm. It makes flashback scenes vivid, saturated, and grainy, like a memory and a dream all at once. It really enhances the reds, greens, and the beautiful cyan. It makes those scenes feel more alive and present.”

—Alan Yang, Director of Tigertail

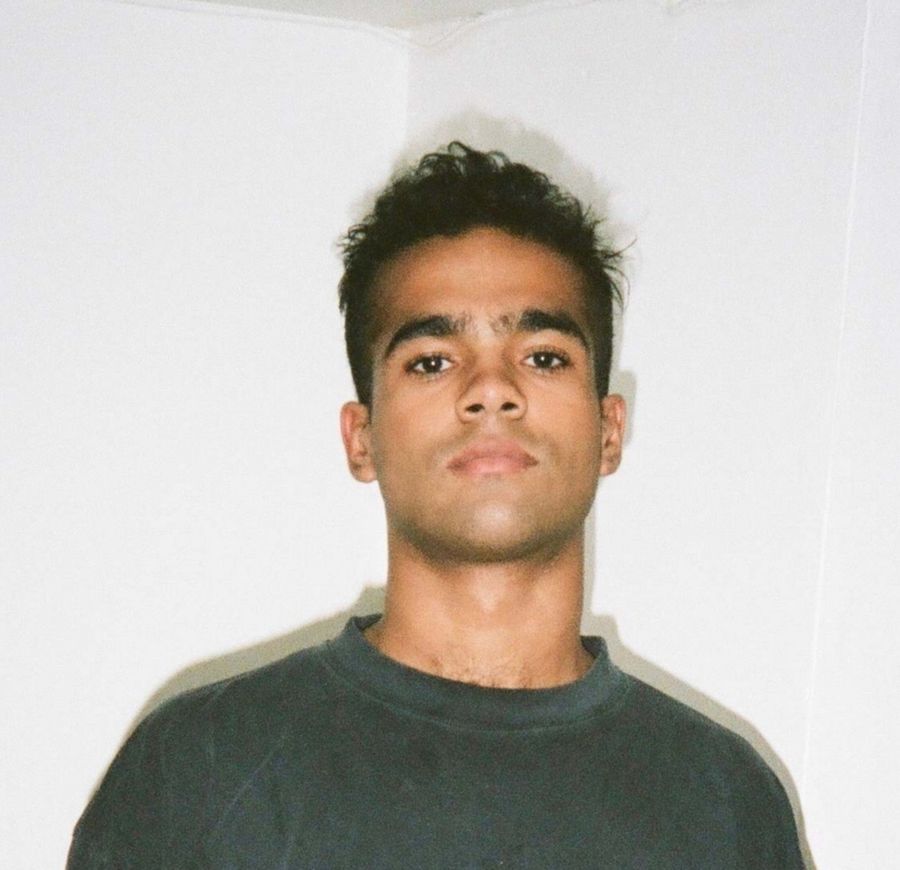

“I happen to love the medium. I didn’t get to shoot my first feature [Gun Hill Road] on film but I did try to. We watched a lot of films for inspiration [for Premature] and a lot of those films from the ‘70s or ‘80s are captured on film. So that was also an influence. By shooting on film, I wanted to capture beautiful young souls in Harlem at a time before it [gentrified].”

—Rashaad Ernesto Green, Director of Premature

MYTHBUSTING FILM

WITH KODAK'S VANESSA BENDETTI

Vanessa Bendetti

Vanessa Bendetti, a CA native born in Los Angeles, has worked in the motion picture and advertising industries for more than 25 years. She began her career at Don Simpson/Jerry Bruckheimer Films and was fortunate to work with Jerry and director Tony Scott for many years. As a research and business affairs specialist, Vanessa has contributed to countless feature films, documentaries and commercials campaigns with clients including each of the major studios, Marvel, RSA, Digital Domain, Mirada, Twitter, Facebook, Google, Nike, UCLA and more. Projects that offer increased opportunity for women are of key priority for Vanessa. Since joining Kodak Motion Picture and Entertainment in 2016, she has enjoyed supporting the analog film medium, and collaborating with the diverse artists who create with it.

Myth: Analog film is a dying medium.

Vanessa Bendetti: We’re seeing great momentum for the medium. Kodak’s camera negative sales have grown significantly each year since 2016, and there are still photochemical labs in most major production hubs worldwide. With the resurgence of film use, post-production houses and other partners in the industry are reinvesting in the infrastructure and workflow for film. More labs and new film equipment are hitting the market, including scanners that can extract information from film at more than 20K. *Filmmakers can search for labs in their cities or production locations here.

Our goal at Kodak is to help educate and support artists so they can make the choice that's best for their project, and not just because they're being told what they should or shouldn't do.

Myth: Shooting digitally leads to the same results that you get on analog film.

VB: I think that when people first started moving away from film and the digital revolution was going on, there was an excitement about new technology and people didn't want to be left behind so they jumped to that very quickly. There was an expectation that it was better. Now, there's digital fatigue, and naturally, an analog revolution. Nobody walks into the color bay and says, "I want this to look like video." Everybody wants to add “grain” and do things to try to make it feel like it was shot on film, and of course the best way to do that is to shoot film. The process is also different. Real film drives a certain discipline, planning, and preparedness from the entire cast and crew, which filmmakers tell us improves and distinguishes their work.

Myth: Analog film is so expensive, it is not worth trying to shoot with it.

VB: That's just not true. It depends on the project, it depends on the filmmaker. In general, in a production budget, they often don't take into account that that film cameras are less expensive to rent than digital, you need less crew, and you can get more setups in a day because you're not tethered to a video village. Film will allow you to get through shots quicker, to move your setups more quickly without all the digital cabling, and you generally have less content to manage in post because of better shooting ratios with film. Then there's also post-production savings, because your footage already has the inherent beauty and texture of film. There are all sorts of things that don't get quantified in budget comparisons, and [Kodak has] a lot of filmmakers say definitively that they couldn't have done their project as economically if they had not shot on film.

Myth: Analog film is inaccessible to emerging filmmakers.

VB: My tip is to work with short-end resellers and look for discounts for film. For example, Kodak offers a discount to students and to schools on all of our film products. What can also be very helpful to emerging filmmakers is how professionals that use film want to protect the medium. Because of that, some of the most accomplished analog filmmakers in the world are willing to teach and mentor the next generation. Kodak partners with trade organizations like the American Society of Cinematographers to offer film-based workshops to the general public. We also have a grant program that was put in place by Kodak a long time ago with the University of Film and Video Association (UFVA). Most importantly, if you’re being told you can’t shoot film, please reach out. Kodak will help you make it work, and give you the information and tools you need to achieve your vision.

Movies shot on film received 37 Oscar nominations in 2020. But what’s also really exciting is the growing use of film in the TV, music, and commercial segments. Succession, Westworld, I Know This Much Is True, The Walking Dead, I Am The Night, and The Eddy are all shot on film, and three of the five 2019 Grammy nominees for Best Music Film (including the winner, Beyonce’s HOMECOMING) were shot on film. I think this speaks to the fact that film can work for any budget and any type of production, and sets it apart from other content.

PREPPING TO SHOOT ON FILM LIKE A PRO(DUCER)

WITH TARA RAZAVI

Tara Razavi

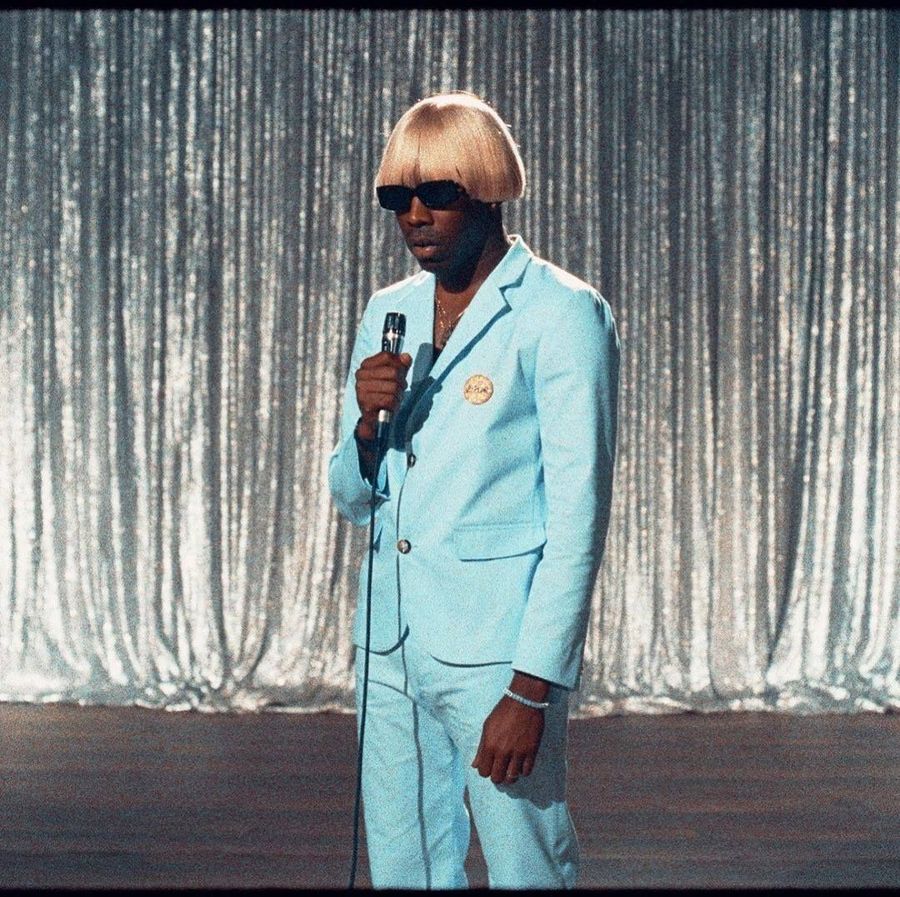

Tara Razavi is the LA-Based Founder and Head Producer of bi-coastal creative production agency, Happy Place, Inc., the company behind iconic music videos such as Aminé’s “Spice Girl," SZA’s “Supermodel," and Tyler, the Creator’s "EARFQUAKE."

Why do you think many music video directors want to shoot on film?

Tara Razavi: The whole analog film process is different and it just feels a little more special and it feels a little more specific. Tyler [the Creator] only shoots on film. Dexter Navy only shoots on film. Vincent Haycock only shoots on film. And it’s even more fun from a creative producer standpoint.

What are the unique advantages of shooting on film for music videos?

TR: Let’s say we’re shooting a music video digitally. You're just shooting a performance for two hours. It's a total waste. And at some point when you have that latitude, it's like a menu with way too many options. If you have three options on a menu, you get very particular and quick.

Is it difficult to incorporate VFX for music videos when shooting on film?

TR: People will be like, well I'm doing a lot of VFX so I need to shoot digitally. But you can scan film 4K. You don't need more than a 4K file for a lot of VFX. So you don't really have limitations there. Safe isn't always the most beautiful. The unknowns in film add so much to its value. And if you try it once, you try it twice, and you catch the hang of it, it's something that becomes really worth it. Sometimes it's about the long game.

How much does analog film typically cost in music videos? Do you have tips for producers to get the best prices for their film?

TR: It's more about how much you want to shoot and how much you can shoot. I just bid everything per foot. If I know I'm going to shoot 10,000 feet for this one performed piece. That might be 55 cents a foot. That might be 75 cents a foot, whatever that is. It's super easy. Sometimes you can get some savings on cameras to offset the cost of film.

Build a relationship with your camera vendor. You might say, hey, I really want to shoot on film but I don't have the money right now. And how many feet can I get for X amount? And then if your DP appreciates film, they'll probably also compromise, right? For example, they might say that they don’t need as many lights. It just takes a little bit of work on the producer side, but it's all doable.

"The unknowns in film add so much to its value. And if you try it once, you try it twice, and you catch the hang of it, it's something that becomes really worth it. Sometimes it's about the long game."

—Tara Razavi

FUELING THE CREATIVE ROOTS: WHY DPs and DIRECTORS CHOOSE FILM

Cara Stricker

Cara Stricker is an Australian born director, music producer and artist. She is known for her work that combines filmmaking with her creative direction, choreography, and expressive narratives. Stricker’s major commissions include creating a four part polyptych instillation and conjunction with the music video for Alicia Keys, avant guard film about the late Aaliyah’s legacy, and album films for Chloe and Halle, Blood Orange, Kelsey Lu, Tei Shi and Kadhja Bonet. Stricker’s unique blend of feminism, nature and performance creates work that is both subversive and etherial. She has collaborated with global brands such as Gucci, MAC Makeup, Chanel, Alexander Wang, Missoni, musicians such as SZA and Perfume Genius, and contributes to titles such as Vogue Ukraine, I-D Magazine, Fader, Dazed and Confused, Interview Magazine and Oyster.

Her work has been awarded and screened internationally including at Raindance Film Festival, Cannes Short Film Festival, Tribeca Film Festival, Berlin Music Video Awards, Toronto Shorts Film Festival, New Orleans Film Festival, Rooftop Film Festival New York, London Short Film Festival, Shots awards, Sugar Mountain festival and Vivid Sydney. Her short narrative ‘Maverick’ premiered at FFFest, and her two most recent mixed media shows exhibited at The Hole NYC. This work continued when she teamed up with musician John Kirby (Solange Knowles, Frank Ocean, Blood Orange, Sebastian Tellier) to direct, perform and produce music for their audio visual album, ‘Drool’, and her solo ambient album and short film ‘Formless’, both released on Terrible Records, with screenings and performances across Australia, LA and New York City. She lives in Los Angeles.

Charlotte Bruus Christensen

Charlotte Bruus Christensen is a Danish cinematographer. She is best known for her work in The Hunt (2012), Far from the Madding Crowd (2015), Fences (2016), and The Girl on the Train (2016).

She earned a degree in cinematography from the National Film and Television School in 2004. After film school she returned to Denmark where she wrote, directed and shot the 2004 short film Between Us.

Chayse Irvin

Chayse Irvin is an Canadian/American cinematographer best known for his collaborations with Director/Artist Kahlil Joseph.

Chayse' first feature film as cinematographer was Medeas (2013) in which he won the prestigious "Best Cinematography Debut" at the Camerimage Film Festival. Soon after Chayse began collaborating with Kahlil Joesph on numerous works of art eventually collaborating together on Beyonce's Lemonade in 2016. In 2017 at the Cannes Lions festival, Chayse won Gold for Sampha "Process", Silver for John Malkovich x Squarespace, and Bronze Apple Watch Series 2 "Go Time". In the same year Andrea Poloraro's "Hannah" took home Best Actress award for Charlotte Rampling and soon after Won, Silver Hugo Best Cinematography at the Chicago International Film Festival.

Chayse is a member of the Canadian Society of Cinematographers and resides in Brooklyn New York.

Were there certain pieces of work that inspired you to shoot on film?

Chayse Irvin: After graduating high school I went to see Road to Perdition which is a film shot by Conrad Hall. It was his last film before he passed away, and prior to that I had studied production design under a mentor in my later years in high school. I was kind of unsure of my path, but I really connected with the cinematography in that film and I was just hypnotized by it, so I decided to alter my career path and become a cinematographer.

Charlotte Bruus-Christensen: My dad is a dairy farmer and my mom was a hairdresser in the middle of nowhere in Denmark. We had no relation to the industry. I wasn’t fed with a lot of movies when I was a child. But I was obsessed with telling stories. I borrowed my parents’ 35mm film camera without them knowing, and I would go out and take 10 or 15 photographs and together that would make little stories. When I was in film school, I did my whole dissertation on Sven Vilhem Nykvist, Ingmar Bergman’s cinematographer. Jack Cardiff too. I could list 20 amazing cinematographers. I feel like they all teach me something different.

Cara Stricker: Cinema started there, which unknowingly shaped the gorgeous feeling I had toward it, and that I couldn’t point my finger on as a child. I started shooting film photography at about 15 and completely fell in love with it. Stephen Shore, Gregory Crewdson, Mark Borthwick, Jeff Wall, to name a few, were image makers that would tell so much of their vision through the language of 35mm and medium format film. It really seemed like a natural progression to move from that instinct into moving pictures when I could. Leaning into being present in the moment and trusting the process of film…Fellini, Antonioni and Agnès Varda’s work on film is really interesting, experimental and inspires my sensibility and they continue to speak to me now. Soy Cuba also resonated on a deep level; it is a great film to look at with reversal infrared stock. That's a crazy film to watch, to see how wide angle lenses and infrared stocks can completely alter film in the most incredible way. Richard Mosse’s use of infrared stock initially created to use in war, comments on contentious civil unrest. It is an incredible example of how the format itself can create such a confronting and complex story within a body of work.

Why do you work in film? How does it elevate the storytelling of your projects?

CI: When I started to work in the industry I was trying to emulate the artists that I had known in my life who were primarily musicians. They always were particular about what kind of sounds they would play or what kind of harmonic devices they would use. It was always due to a certain constraint of the instrument, and I became really fascinated by that process. The more challenging the format is, the more you enter what's called a flow state when you're operating unconsciously and you're just exuding and responding to things around you. It demands more of you, so it just brings out excellence.

CBC: I feel like it’s a very truthful media. It helps me focus on the story and stay true to the story. I just feel like you have to use all your filmmaking muscles when you’re on film. I feel it’s always pushed me to be better and to stick to the story.

CS: I honestly believe that what you’re seeing [on film] fuels an emotionality that instinctively feels more textual and has more depth than you can achieve with digital. It pushed the whole team to be present each take, to that moment, embracing what comes a sense of natural ease, rather than overworking a certain frame time and time again. Everything seems more focused, and helps me focus completely and listen to my instincts. I love how the processing of the film interacts with the environment, to define our language, and enhance our world.

"Throw yourself in it, try not overthink it, and try without fear! Even do that right now inside your house."

— Cara Stricker

In your opinion, what kind of projects call to be shot on film?

CI: I focus more on: How do I create something simple that's still really interesting? It becomes about trying to create, to hypnotize the spectator, to pull them into the image, even though it's maybe not full of information or plot or it's constantly moving. How do I capture that same feeling that's almost like a really amazing still photo from Henri Cartier-Bresson or William Eggleston or Roy DeCarava? How can I craft just a single frame that you can stare at forever?

CBC: I’m a person that would find every reason to shoot on film. For example, I recently shot a film called The Banker. It’s a period piece, so I immediately knew that I wanted a celluloid look. Initially, everyone went against it, but I told them that in the end [shooting on analog film] actually costs less money than having to pretend. So I’d say if people want a “filmic look,” it’s so obvious that you need to shoot on film.

CS: I shoot everything on film if I can. I think it adds a very specific feeling to a piece that you can't replicate with anything else. I’ve recently experimented with a technique when you can’t shoot on film, like working with a super fast camera for slow motion, and printing to film afterwards. Taking the digital film and projecting it onto a stock, and then digitizing it again. I wouldn't recommend that as a go-to, the process creates a different feeling, but it's definitely an interesting process.

Are there any unexpected challenges that people should be aware of before they show up on set?

CI: There's always these little details about [analog film] that you don’t consider if you shoot digitally. Say you're shooting a scene and there's dialogue in the scene. You have to ask yourself: How long can the camera record? Well, you have different magazines with film. You have a 1,000-foot magazine. You have a 400-foot magazine. Both those loads affect the size and weight of the camera, so you're constantly negotiating in your mind what is necessary to capture this moment. Do I want something that's smaller so I can get [the shot] really quick because the light's fading? Or do I want to plant the camera and focus on the composition to just allow the director to pull different variations of the same dialogue?

CBC: Test your lenses and the camera bodies and make sure everything has been thoroughly checked so you don’t have any unexpected pitfalls or terrible surprises when you see the results three days later. It’s happened to me. You have to go back and reshoot, and that’s when people regret not checking thoroughly. But it’s not that you never make mistakes on digital. You have to be precise, no matter what you shoot on.

CS: Checking the gate every shot. A hair in the gate can be looked over and you only find out at the very end in post. So you might've done something incredible, but because there is a tiny little thing in the lens, you would have to do it again. That particular moment is a challenge on every set. You also have to trust everybody because if your focus puller didn't nail it, you're only going to find this stuff out in the edit bay. Just make sure you have the right team.

How does working on film impact the crew and tone of the set?

CI: You can see how people feel more engaged and how the crew feels more engaged and more connected to the process, which is so, so valuable. As a cinematographer, I need that support. I need that engagement from my crew, so not only does the format fulfill my desires for aesthetic reasons, but it fulfills my desire to connect with the people who I work with. The support necessary is greater from your team on film, so it's just always a joy.

CBC: You don’t need many more people on set, you just need different roles. On film, you don’t need a DIT but you need a loader. The loader loads the film into magazines that go into the dark room. You need a person that can make sure you loaded enough magazines for the right film stock. That loader has a close collaboration with a clap loader so they can label cans of film correctly. In general, film brings everybody on set. No one’s sitting in a DIT station six rooms down the corridor. With film, there’s more straightforward communication, which is good for directors who want close collaboration.

CS: No one's looking over your shoulder to check every image, which I think makes the talent and the people in front of the camera able to lean into what they're creating rather than feeling super self-aware. So there's a whole level of

artistry and freedom that they can tap into. All you need is your DP, a camera loader, first AC, a grip if you using lighting, focus puller, and you're good. You can create so much work with a very stripped back small tight unit. I've done that a lot and I love it. There are cameras that you can shoot and operate alone as well, which makes the process even more intimate.

Do you have any advice for emerging filmmakers who may feel afraid of using analog film for the first time?

CI: Oh, man, fear is the worst. I think you have to get out of that fear and go out and just go for it, I think. A year ago, I worked on a short film with some friends of mine. We went to Arkansas to start the short film and we shot for six or seven days on 35 mm. We had no money and every frame mattered. It gave us an incredible amount of willpower and it allowed us to all connect in an amazing way.

CBC: You will always be scared when you go out and do your scenes. You’re just nervous and you want to do well. For DPs, you want to trust your eye, your viewfinder, and your light meter. Even when you shoot on digital, you should be able to know what your frame is without looking at a monitor. To train your eye, observe natural light. Be very aware. It’s about observing and figuring out what you like. It’s all about opinions. There is no right or wrong. How you train your eye is very personal. Look outside your windows. Give yourself time to sit and watch and observe light and make up your mind about what you like and why you like it.

CS: Shoot as much as possible so you get familiar with things you like, your mistakes, and how to push the film in ways you like once you understand its nature. I think you need to be doing personal projects and experimenting, and creating, and leaning into what you love story and subject-wise whether that's sculpture, music, dance or it's video installations or narrative filmmaking. And then… do as much of that as you can, and it will inform your career and filmmaking. Throw yourself in it, try not overthink it, and try without fear! Even do that right now inside your house.

THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS MATERIAL IS PROVIDED FOR GENERAL INFORMATION PURPOSES ONLY AND IS NOT MEANT TO BE BUSINESS, LEGAL, FINANCIAL OR OTHER ADVICE NOR IS IT AN ENDORSEMENT BY FTW OF ANY PRODUCTS OR SERVICES MENTIONED THEREIN. NO INFORMATION IN THIS MATERIAL SHOULD BE RELIED UPON FOR SIGNIFICANT PERSONAL, BUSINESS, LEGAL OR FINANCIAL DECISIONS. PLEASE CONSULT WITH THE APPROPRIATE PROFESSIONAL, FOR SPECIFIC ADVICE TAILORED TO YOUR PARTICULAR SITUATION.