FTW’s MEET series is a new editorial column highlighting up-and-coming FTW filmmakers sharing groundbreaking work with fresh takes and fresh perspectives.

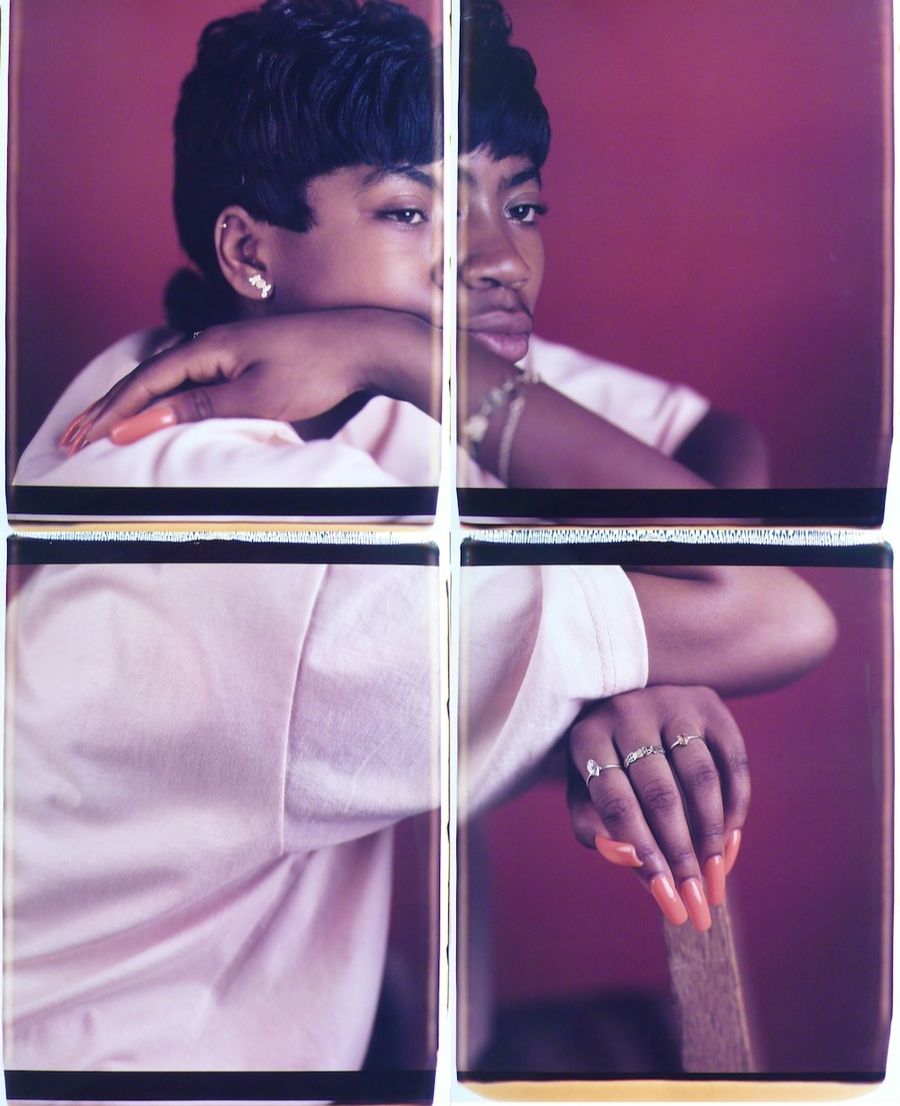

Haley Elizabeth Anderson is a filmmaker with roots across the American South and Gulf Coast. Her work immerses you in a surreal and poetic perspective on family mythology, memories, and human vulnerability. Through her experiences street casting for a Terrance Malick project, she cemented her love for collaborating with first-time actors. Her unique approach to her craft lands in a beautiful hybrid of narrative film and experimental documentary.

Selected as one of Filmmaker Magazine's "25 New Faces of Independent Film 2019," she graduated from New York University’s Graduate Film Program as a Dean’s Fellow. While there, she completed her thesis film, “Pillars," which was created through Spike Lee’s annual production fund. The poetic short film is a meditation on family mythology, identity, and coming of age. With brilliant performances, dynamic cinematography, and an ethereal and exploratory score, Haley has a very clear voice, vision and presence.

“Pillars” premiered at the 2020 Sundance Film Festival, and is now having its online premiere on the Criterion Channel in the Age of Exploration collection alongside Céline Sciamma’s Girlhood. Watch the online debut of Haley’s visionary short “Pillars” below and continue reading to learn about Haley’s roots and mythical approach to her craft.

FTW: There is such a strong presence of surrealism and magical realism in your work – what do those things mean to you and can you expand on why they are so important to you?

Haley Elizabeth Anderson: It all comes from the impression or presence that one person can have on you. I think that is a through line in all my stories. Even in the absence of someone, there’s this lingering presence and something that we all find that we need. I was trying to express that visually. I’m always trying to express what is running through my being. Or what is running through my grandparents. I’m always trying to capture visually what that feels like or what I imagine it to be like. Even though it is real, you create your own family mythology. It’s all in your head.

I’ve heard you talk about genetic memory both in terms of "Pillars" and your future features. Can you talk about what genetic memory is? And how that carries over into your films?

Genetic memory is the study of how trauma or major events in your life affect your genes. It’s based on the study of Holocaust survivors and the levels of cortisol that they had inside of them. They studied their great grandchildren who didn’t go through the Holocaust, and found that their cortisol levels were higher than other people who didn’t have a link to the Holocaust. There has never been a study on African Americans and the African diaspora, so I was really interested in thinking about it both imaginatively and scientifically. I want to mix the two together and explore how these things that have happened to us in history are affecting us.

Picking that apart, I want to analyze everything: the good things, the small bits, and the strange occurrences that affect us. How have our grandparents affected us through small decisions? That’s through our bodies, the way we do things, and the way we think. How much are we linked? And what are we inheriting from places that we didn’t expect? Is there a person in the middle of Scandinavia that is linked to someone in the Congo? What are those links because of the slave trade and other things? So asking these questions. It’s not concrete. I don’t think I’m looking for definite answers, I’m just trying to explore it through the lens of the African diaspora.

What was the genesis of having a pillar of fire in this short?

I really wanted to put the image of the Pillar of Fire in a film. I think it came from watching 2001: A Space Odyssey and seeing a recurring image of the monolith. I was thinking about what image in my family history is important. I was thinking about being in church and the stories you’re told. The biggest image besides the Red Sea is the Pillar of Fire. And it’s bizarre. When you’re raised in church, you don’t think about the weirdness of that imagery. I wanted to see that kind of imagery in a film. I always had that image on hold. Even though the Pillar of Fire is a creepy image to me, the fire is supposed to be comforting because it is guiding you. I love things that make you feel small and powerless, yet also comfort you. When I came up with “Pillars,” it came from a screenwriting exercise in school about pain and guidance in a series of small vignettes. It felt like the perfect opportunity to put the Pillar of Fire in as a monolithic image as well as an ambiguous ending.

Your style and tone feels so unique and clear. How do you convey or communicate the tone you’re trying to capture to your collaborators?

I always start with photography, light, sounds, memories, and feelings. It’s all visual and geographical. The films that mean the most to me are shot in the South because it’s the perfect quality of light. I start with certain feelings, like a neighborhood where you’re in the middle of the street. What does it sound like? What does it feel like? And then I find photographs that evoke that feeling.

It’s definitely not concrete. When I first talk to my collaborators, it is always about the feel. From there, things become more concrete. I also think that the people that work with me now know how I think about things and how it all starts. My editor definitely gets it because it’s also his style too. Somehow it all comes together but I think we’re all interested in a feeling rather than what makes the most sense.

The writing style of "Pillars" feels so confident and beautiful in the way that it doesn’t rely on lots of dialogue. How do you write in that way?

This was the film where I tried to put more dialogue in, but it didn’t work. I write through paradoxes and details. In the edit, I realized that the dialogue I had written in was unnecessary. Because I started out early in my career not being comfortable with dialogue and trying to express my ideas in different ways, it has become something that I’m used to.

Do you know when you’re writing what moments are going to become more dreamy versus which ones are more grounded in reality?

“Pillars” looks pretty much like how I wrote it, but there were times where I had to follow what was happening on set. Sometimes a location doesn’t feel like how you wrote it. You have to go with the vibe of what the location is giving you.

How much research did you do into your family before making this?

I ended up mostly channeling more memories than than being in the actual spaces. “Pillars” was based on the town that my mom grew up in and I was supposed to shoot in my grandfather’s church. We lost the original location of the church right before shooting and found the new location the day before we shot that scene. It was intense, it wasn’t easy. I was trying to find places where you could walk in the middle of the street without getting run over. Neighborhoods that feel like that. The way the sun shines through the curtains. How I remembered my grandmother’s house. My grandmother’s house had this paneling, but we were shooting in New Orleans. There were no houses there with paneling because of Katrina. Most houses had been remodeled, so we had to re-panel the living room with wallpaper. I’m not sure if it is noticeable, but for me, it feels right. In the end, it doesn’t feel necessary, but in the making of, it feels very necessary. So hopefully that comes across.

I read that you want your sets to be places where the crew leaves and says, “That was a great experience.” I feel so strongly about this, too. What has your approach been to create a safe, beautiful on set environment?

I believe in making sure everybody is okay and fed. I don’t believe in shouting on set. It’s just a movie. Yes, I’m very serious about my work and what I do, but at the same time, we’re living in reality. Look around and put things in perspective. You can’t treat people like they’re nothing. Even if things are going badly, relax. We lost a lot of locations; nothing is going to be perfect. Understand that from the beginning. It’s stressful already and getting upset is not going to help you think about solutions.

There are a lot of people who say, “I don’t take no for an answer.” I don’t believe in that. There is no such thing as no; there’s only a different way to think about it and to find a solution. I don’t believe in trying to manipulate people or taking advantage of communities and people that are unaware of your agenda.

There are a lot of ideas of what a traditional director is that should be retired. It has nothing to do with not being a hard worker or not expecting a high level of commitment. Everybody will give you more if you respect them. We’re all learning and we’re all in this together. I want to be in direct communication with my crew to make sure everybody’s alright, and I want to make sure the producer takes on my tone to the crew so that no respect gets lost.

What do you think makes a good director?

Making eye contact with people and making them feel like they’re not invisible. I’ve been on many sets where this isn’t the case. It's very frustrating when the crew doesn't expect you to be the one leading the project. I want to know everybody’s name and what they’re doing. There’s an idea that being genuine and sincere is super cheesy, and I hate that. Everyone appreciates being talked to with respect and like a human being. And at the end of the day, you get to have fun and make a whole bunch of new friends. What’s not to like?

The cinematography feels so intuitive. How much was decided beforehand versus spontaneous creative decisions on the day?

Much of it was decided beforehand because we knew how hectic the shoot was going to be. When I wrote “Pillars,” I thought it was going to be my ‘formal film’ and have a more formal visual style of being all on sticks. Then when we got to set, we knew we wanted and had to shoot handheld. We don’t have enough money for a Steadicam, but my crew knows the kind of handheld style that I like. It has to be as smooth and poetic as possible as well as being reactive to the subject, so we went into shooting with that in mind.

I also have certain ways of communicating things to my crew. If there’s a photograph in our references, I’ll be like, “Oh do that picture” and name the photograph on set, and my cinematographer will know exactly what I mean. We don’t copy the photo, it’s just that it captures an angle, a type of light, or a moment that we need on screen.

Can you talk a little bit about the way the kissing scene is shot. Especially the moments right after. Choosing to be in such intense close ups and having the camera look right into Jackie and Amber’s eyes.

We had this Dawoud Bey photograph as a general reference beforehand. I loved the fragmenting of people’s faces so that was a big inspiration. But that reference was never meant to be recreated on set. I wanted that whole scene as a two shot with dialogue. But my lead actress, Kadence, was so young and felt uncomfortable with the kissing. I would never force her to do the scene in real time over and over again. So I was like, okay, we’re going to have to make this feel a little bit more intimate than it actually is. So we scrapped our original shot and felt like this was the perfect moment to do the fragmenting concept. And that’s how we got the close up details of their faces.

In those moments where things are going wrong and you have to be on your feet and problem solve, what things do you do to stay present?

When things go wrong, I won’t freak out on set. All the crew is there and they’re only here because of me. If I don’t know what to do, I feel like an idiot because I just dragged them to the middle of Louisiana. That’s my biggest insecurity. My whole mantra is that something is going to be on screen and you’re going to be in the editing room in a few weeks. What are you going to see? It might not be what you originally had in mind, so pick what you’re going to see right now. What are you going to need practically? How can you cheat this? Part of it is making it look like you know what you’re doing while you’re trying to figure it out.

I heard you talk about how “Pillars” is about who gives you permission to be what when. When do you have permission to be who you are and how somebody can take that away from you—can you expand on this?

I went back to my own childhood and thought about when I felt unable to express who I was, and seeing other kids in church being reprimanded for tiny things that were just a part of their personality. Growing up in the South, there were sayings like, “Don’t speak until you’re spoken to.” Just weird things that are accepted by people to say day to day. I was thinking about those instances where you’re trained to be a certain way before you can even develop as an individual. It always stems from tradition, places where you have this complicated relationship. Church was a comforting place with your family and friends, but I always had my church self and my real self. That’s also where the idea of the Pillar of Fire came from. It’s this entity that seems to be against you, but is actually for you.

What filmmakers, films, or photographers inspire you?

I love Lynne Ramsay, Andrea Arnold, Les Blank, Terrence Malick, and Mati Diop. Also Roberto Minervini, he’s a documentary filmmaker, but he hides the fact that it’s a documentary in the way he shoots it so it feels like a narrative. There are so many great photographers, but I love Deana Lawson, Dawoud Bey, Stephen Shore.

Can you talk about Coyote Boys and Gulf —the features you’re working on?

Coyote Boys is about this kid looking for his brother, but it’s set in a world where people are hopping trains. It’s a road movie through the lens of a young Black man. It’s also inspired by my grandfather. Going back to the idea of family mythology, there’s this story that my grandfather was hopping trains for two years and constantly disappearing. I was always curious how he survived being Black in the 1940s. How does that translate in a modern context? Even with the pandemic now, it’ll be interesting how the story will change. Ultimately, Coyote Boys is about survival in these working class, marginalized communities when you feel like you’re living with a chosen family, rather than real family. What happens when the feeling of being lost and drifting feels more like home than a traditional home?

Gulf is a continuing project. It’s something that I don’t think I’ll be able to make unless I have a bigger budget. It’s about the African Diaspora so there’s a lot of traveling involved with that project that’ll have to be funded. It’s more in the dreaming stages right now.

What is your goal for future generations of storytellers and filmmakers?

I would love to see the inclinations of people change. What people expect the people in charge to look like. That needs to change. When you change what success looks like and when you change what the people in charge look like, things will change on set. It’s about changing the faces of leadership and providing access. I think filmmaking is a way for people to learn about different cultures and places. I completely believe in the power of film to do that. At the same time, I’m looking forward to seeing movies made by people from particular places for themselves. I’m not interested in seeing things that aren’t authentic. I believe in swapping stories and sharing cultures, but there is a power when you see a film from four corners of the world made by a person from that place. I want to see stories from people we don’t ‘traditionally’ expect to be directors. People owning their own stories.

We have so much work to do. When I was in the Queen Collective, Queen Latifah said, “I want my sets to feel like the world looks.”

What is your biggest piece of advice to other aspiring filmmakers?

Don’t be afraid to ask questions.

I’m still trying to stop apologizing for feeling dumb when I ask questions, but who cares? One director said, “Every time I get on set, I feel like I don’t know what I’m doing.” Somebody knowing what they’re doing all the time is false.

Contact the people you look up to. Just be ruthless about getting information; there should have not been anything hidden when I was in film school. Even with my professors, everything felt like a mystery. The first person who came into a class and shared all of his resources was Reinaldo Marcus Green. Nobody did this at all. Most people were just like, “I got into this film festival and look how great my life is going.” And you were like, “What do you do?” But people like Green, they’re just so giving. There should be no secrets to sharing resources and levels to unlock, you know?

Haley Elizabeth Anderson

Haley Elizabeth Anderson is a filmmaker, writer, and photo-based visual artist from Houston, Texas. She recently graduated from New York University’s Graduate Film Program as a Dean’s Fellow.

With roots across the American South and Gulf Coast, and a background in playwriting and poetry, her work revolves around indefinable emotions in memories, coming-of-age experiences, familial mythology, and the ever-growing class-divide through mundane moments of human vulnerability and intimacy. Although her work is often a meditation on personal histories and identity, she is interested in examining these ideas within the global landscape.

Her experiences street-casting a Terrance Malick project in Austin, Texas led her to further develop her love for collaborating with first- time actors, a process that drives part of her aesthetic: a hybrid of narrative film and non-linear, experimental documentary.

Her work has been featured at the Barbican in London, The Shed in New York, Le Cinema Club, the Criterion Channel, International Film Festival Rotterdam, and Sundance. She was recently selected as one of Filmmaker Magazine’s “25 New Faces of Independent Film.”

She is currently in development for her first feature, Coyote Boys, a contemporary odyssey through fringe communities, centered on rootless youth experiencing loss and loneliness— finding alternative ways of surviving 21st century America. The project was selected for the Sundance Institute Filmmaking Program, IFP Week, TFI All Access, and SF Film’s Westridge Grant.

María Alvarez

María Alvarez is an internationally recognized Cuban-Dutch filmmaker. She graduated from the University of Southern California with a BFA in Film & Television Production in May 2019. Her passions are centered on raising awareness for diverse female stories about sexuality, identity, and coming of age. Her films have screened at dozens of festivals such as the Los Angeles Film Festival and Cleveland International Film Festival, won awards from institutions such as Google, and screened in museums like MoMA. Her short film, "Backpedals", screened at the 2018 Festival de Cannes in the Court Métrage and was a finalist in the 2018 Horizon Awards, an all-female Sundance sponsored fellowship. She is a YoungArts alumna and is featured on the 2018 YBCA 100 List. She worked as a Director’s Assistant to Benedict Andrews on Seberg, starring Kristen Stewart and shot by Rachel Morrison. She is in the festival circuit with her senior thesis film, "Party of Two", which premiered at Outfest Fusion. She is currently the Creative Editor at FREE THE WORK, the global talent discovery platform for underrepresented creators founded by director, Alma Har’el.