All images courtesy of Kira Dane and Katelyn Rebelo, unless credited otherwise.

“Mizuko” is a deeply intimate portrait of a woman’s search for emotional healing after an abortion, based off of screenwriter and co-director Kira Dane’s personal experiences. While searching for a way to process her abortion, Kira, who is half Japanese, discovered that in Japanese culture, there is a specific word to describe an unborn life: mizuko or “water child.” Kira also found a Japanese ritual for grief that allows women to metaphorically return their water children to the sea. Told against this cultural backdrop, “Mizuko” provides a unique alternative to America’s often politicized binary view of abortion, in a way that gives space for emotional healing.

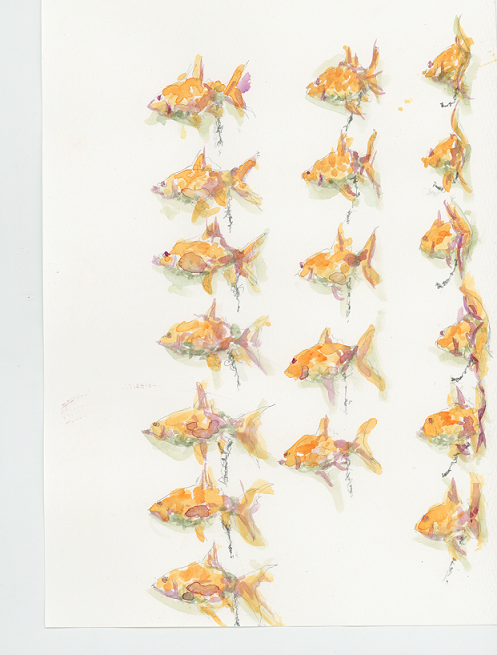

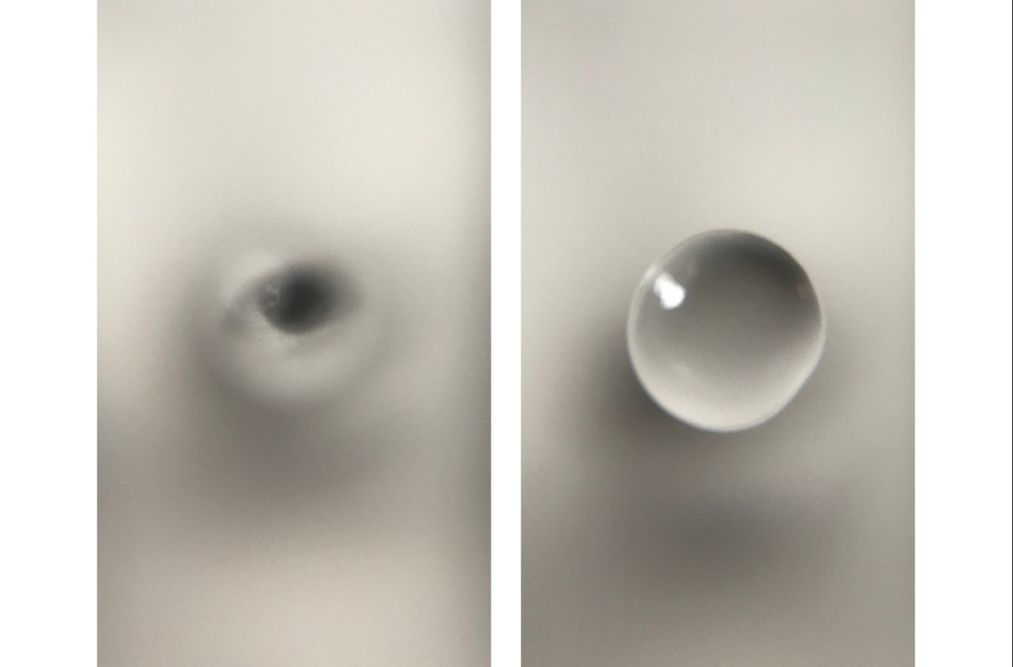

One of the remarkable aspects of the film is its unique use of animation as a way to portray metaphysical concepts and emotions. The story unfolds through a poignant mix of Super 8 film, watercolor, and stop-motion animation, making it a testament to how animation can open up new avenues for expression in filmmaking of all genres.

Here, Kira and co-director Katelyn Rebelo detail the creative process behind their eye-opening short film. “Mizuko” is available to stream on Amazon Prime from now until May 6.

How did the idea for "Mizuko" first come about?

KIRA DANE: I got an abortion in 2017 and at the time, it was shocking but still a fairly simple problem to work through in my life. I lived in New York, so it was easy enough to get access. I had insurance that covered the bulk of the cost. I was able to make an appointment for two days after I found out, I went with my mom, and it was over very quickly. But emotionally, I had no proper tools—I wasn't really equipped to deal with it at all. And I think that’s because, if you’re pro-choice in the US, the kind of default attitude is to just see it as a normal health care procedure.

But months after experiencing it myself, I ended up realizing it affected me a lot more than I had initially thought. I am half Japanese, so I started looking into Japanese culture around abortion and found this amazing alternate path in a Buddhist ritual that people have been doing for centuries. One that doesn’t box-in the act of abortion as moral or immoral, but instead offers relief for people who have had to make a really difficult choice. As soon as I heard about that, I realized it was a really important story to tell. I couldn’t find a single person I knew in the US who had heard about it before. So I wrote this essay about the Buddhist concepts behind the mizuko kuyo rituals, and how it tied into my own experience. Katelyn and I used that essay as a backbone, and we closely collaborated to edit and translate it into an animated documentary project.

KATELYN REBELO: We really wanted to recontextualize the idea of abortion in the United States. Having an abortion is an incredibly personal experience, but the way we talk about it in this country is so political, and often only seen religiously through the lens of Christianity. We’ve created these two sides that aren’t actually speaking to each other in any way, and have removed the ability to feel anything that might exist in between them. So what we wanted to do was create a film that not only introduces people to a Buddhist ritual they may not have known about before, but also create a space for emotional healing for anyone that might need it. And show how having an abortion can be an emotional experience, and that that’s okay.

KD: I think people are afraid to admit to any harm in having an abortion, because that might leave a weak spot in the political argument. I’ve heard people compare it to the removal of a tumor, just removing an unwanted cluster of cells in your body. But I think that attitude ironically does more harm than good in making a strong case for abortion access, because it completely shuts down all the complicated nuances of what it’s actually like to have an abortion. I just wish more people could admit to those nuances in the US, and show each other more empathy for them.

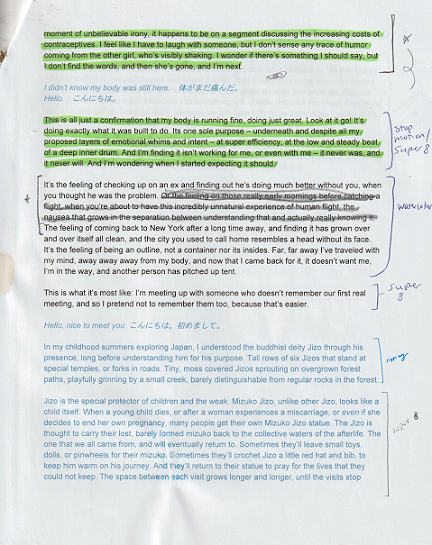

KR: The essay Kira wrote was around 20 pages long, and moved in out of of childhood memories, current realities, internal emotions, and across locations and cultures, all while exploring this relationship between mind and body while following her personal story of abortion—so we knew it was going to be a complex film to make. We wanted this complexity to stay intact, while also creating a film that could be accessible, and equally informative as it was emotional. We decided on the visual breakdown pretty early on and knew that we wanted clear distinctions in medium, language, and texture to speak to specific themes in the film—but we gave ourselves some freedom in the structure and were moving sections around up until the very end.

"What we wanted to do was create a film that not only introduces people to a Buddhist ritual they may not have known about before, but also create a space for emotional healing for anyone that might need it."

—Katelyn Rebelo

"[Animation] worked really well to try to show the two opposing [attitudes toward] abortion and allowed for a lot more experimentation."

—Kira Dane

You two co-directed on this film. How is directing animation different than directing a live-action?

KD: The kind of animation we do is super time consuming. We did everything frame-by-frame. Trying to do everything frame-by-frame for a 15 minute film was kind of insane in the time period we had, considering we also had to go to Japan and do a [Super 8 live-action] shoot there. Every time we had a shoot, we would end the shoot saying, "Wow, this is so refreshing to be able to go shoot something and be done with it. We have this amount of rolls, when we're done, we're done. We send it off to be processed and scanned and that's it." With animation, you never really feel finished.

KR: Animation also allowed us to work outside of the constraint of any equipment or crew, which was incredible, but it did feel like we could continue redoing. I would be like, "Okay, I'll just fix this one last thing." That could turn into five more days or fixing everything that we had already done. So in a way it's much harder to let go of an animation than it is to let go of a live-action shoot.

You also worked with other animators on the project. How did you communicate with them and make sure that they understood the styles and tones you were going for?

KD: It definitely was hard, in terms of a watercolor animation. We had two other main watercolor animators and they were both working remotely from home: Joyce Zhao, who's based in China and Melissa Garvin, who was in New York. We had never directed an animated piece of this scale before. Normally you'd have an assembly line and people doing very specific things within the animation. But this was different, we just had each person doing sections. So the hardest thing was trying to make the styles cohesive enough. That being said, both of them did a really, really good job.

KR: Melissa had never animated before. She was a watercolor painter and we taught her how to animate for this project. It was basically just rotoscoping (tracing video footage). She was already a talented painter so it worked out. And Joyce was also just a close friend of ours. That influenced a lot of it and made it a very easy and natural collaboration with her.

Can you talk about the outlines and storyboards you used for the short?

KR: I had [storyboards] in a box in my apartment that I went through last night. It was funny because nothing we did in those initial plans actually ended up in the final film. Everything changed throughout. It just shows that this was really an ongoing and fluid process. We were constantly doing new things and trying out different forms of animating to see how they worked together.

KD: At the same time, we very carefully chose what type of visual medium went with specific themes in the writing. [The film shows] rural Japanese culture and belief systems, compared to the very lonely and detached experience of having an abortion on a cold January morning in New York. We knew we wanted to have these two divergent narratives reach a point of convergence at the end, and kind of come crashing together, both in the writing and with the visual styles. A lot of Buddhist practice is centered around unifying the separate definitions you have for your mind and your body, and realizing that the idea of self is just a mental concept. One that can be broken down pretty easily, and can’t be delineated from everything else if you really examine it. These are concepts I knew intellectually, but it all became much more clear to me when I understood it physically, when my own body began the process of growing a new person. So creatively, there was a lot to experiment with there, in terms of showing the lack of distinction between mind and body, my ‘self’ and all other living things, or me and my “water child.”

What software did you use to make the film?

KD: We used Adobe Premiere, Photoshop, and After Effects. Photoshop and After Effects were used on my end to put all of the watercolor together. And then once that was assembled, we threw it into Premiere.

KR: Dragonframe is used mostly for stop motion. It allows you to view the frame before and see what you had done and then line it up with what you're currently doing. So you kind of have something in real time while also seeing the previous frame. If something looks wrong you can go back and change it pretty easily. We didn't actually have enough money to use Dragonframe, so I used the software that came with the Canon DSLR camera called Canon EOS Digital to just make sure things were lining up with each other.

How long did each part of the process take?

KR: The bulk of [making the film] was January of 2019 through October of 2019. There was probably about a year and a half before that where we were researching and Kira was working on the writing and we were just planning and figuring out how this was all going to be possible. Animation wise we did the bulk of it in the first four or five months of 2019 and then, after that, probably spent another four or five months either redoing stuff or trying things in a slightly different way until we finally got everything the way we wanted. Does that sound right Kira?

KD: Yeah. Then, we had a month in between all the animation to go to Japan and do our shoot there. We finished in the fall in October. But we had a post house called Sim that was part of the grant package that we got from Tribeca. They did all of the sound design and color. That took like two months.

Since animation is so labor intensive, was funding an obstacle?

KD: This whole project happened because we got this grant from Tribeca. Before we got that grant, we had been submitting to a lot of other grants and we weren’t having any luck. Before we got the grant, we thought that the best case scenario [for “Mizuko”] was uploading it on Vimeo and hoping people would stumble across it. We really did not have enough resources or money to make anything like this. But once we had the funding, it gave us that leeway to be able to make it in the way we wanted to make it. Although I will say, it was still a tight budget. If we were doing a live-action short, it would have been a super comfortable budget. But because we went super ambitious and were making frame-by-frame animations, developing rolls of Super 8, and traveling to Japan, it was just a matter of trying to constantly make sure we didn't spend too much in one area.

Do you have any tips on how animators or filmmakers in general can differentiate themselves and get opportunities?

KD: We really focused on the subject matter, and how we wanted this film to say something new, and what impact we wanted to make. Because we were really clear on that, I think Tribeca was very open to how we wanted to make it stylistically. So in our case we'd probably just say to focus on a really unique story and unique subject matter.

Below, in Kira and Katelyn's own words, are specific references and texts that guided them as they made the film. If you need any more inspiration, be sure to watch “Mizuko,” which streams on Amazon Prime from now until May 6.

The motivation for having distinct Japanese and English sections was a combination of exploring Kira’s personal identity, while also subverting the American political two-sided argument of abortion. Since so much of the film is rooted in a Buddhist ritual, we also wanted to explore these practices and incorporate themes of meditation and the connection between mind and body in creative ways. By the end, the two sections are seen in their opposite mediums, and everything merges together, pointing at the inability of dividing anything (views on abortion, personal identity, mind, and body) into two clean sides and really diving into and finding comfort within the gray area of morality.

Books

LIQUID LIFE: Abortion and Buddhism in Japan by William LaFleur. Princeton University Press: Princeton, N.J.

This book lays out the Buddhist concepts behind the mizuko kuyo ritual in Japan, and it is an account of how abortion has been perceived throughout history in Japan. It was a really great resource for Kira personally when she was writing the essay for the film, and acted as a guide for all concepts related to the mizuko kuyo ritual in Japan. It sparked a lot of conversation between Kira and Katelyn for the thematic rules they created for the film, and provided a lot of ideas for visual metaphor.

"Right before everything in the film comes together, the absence of visuals was intended to create this same mysterious trance-like feeling, bringing awareness to sounds rather than images, the viewers own stillness + body, and evoking a peaceful feeling of floating for a moment before everything builds and merges together."

—Katelyn Rebelo

In Praise of Shadows by Jun’ichiro Tanizaki

An essay that examines the appreciation and importance of darkness in Japanese aesthetics.

Specifically a section about using dark soup bowls was used as inspiration for the moment in the film around 10:21 (11:28 on Amazon Prime) when everything goes dark.

“There are good reasons why lacquer soup bowls are still used, qualities which ceramic bowls simply do not possess. Remove the lid from a ceramic bowl, and there lies the soup, every nuance of its substance and color revealed. With lacquerware there is a beauty in that moment between removing the lid and lifting the bowl to the mouth when one gazes at the still silent liquid in the dark depths of the bowl, its color hardly differing from that of the bowl itself. What lies within the darkness one cannot distinguish, but the palm senses the gentle movements of the liquid, vapor rises from within forming droplets on the rim, and the fragrance carried upon the vapor brings a delicate anticipation. What a world of difference there is between this moment and the moment when soup is served western style, in a pale, shallow bowl. A moment of mystery, it might almost be called, a moment of trance.”

Spirited Away / Courtesy of Studio Ghibli

The train scene in Spirited Away was a big inspiration for the film as well! The visuals and emotion of this scene influenced the shot we have of the train going by the sea in Japan, and we gave the music from the scene as a reference to Midori Hirano, who scored the film.

Additional Texts

Mourning My Miscarriage – Peggy Orenstein

Mourning the Unborn Dead: A Buddhist Ritual Comes to America – By Jeff Wilson. Ann Gleig. Rice University.

NPR: Adopting A Buddhist Ritual To Mourn Miscarriage, Abortion – By Deena Prichep

Pro-Life, Endless Births: Buddhist Views on Abortion – By Karen Jensen with Jeff Wilson

The Cult of Jizo– William LaFleur

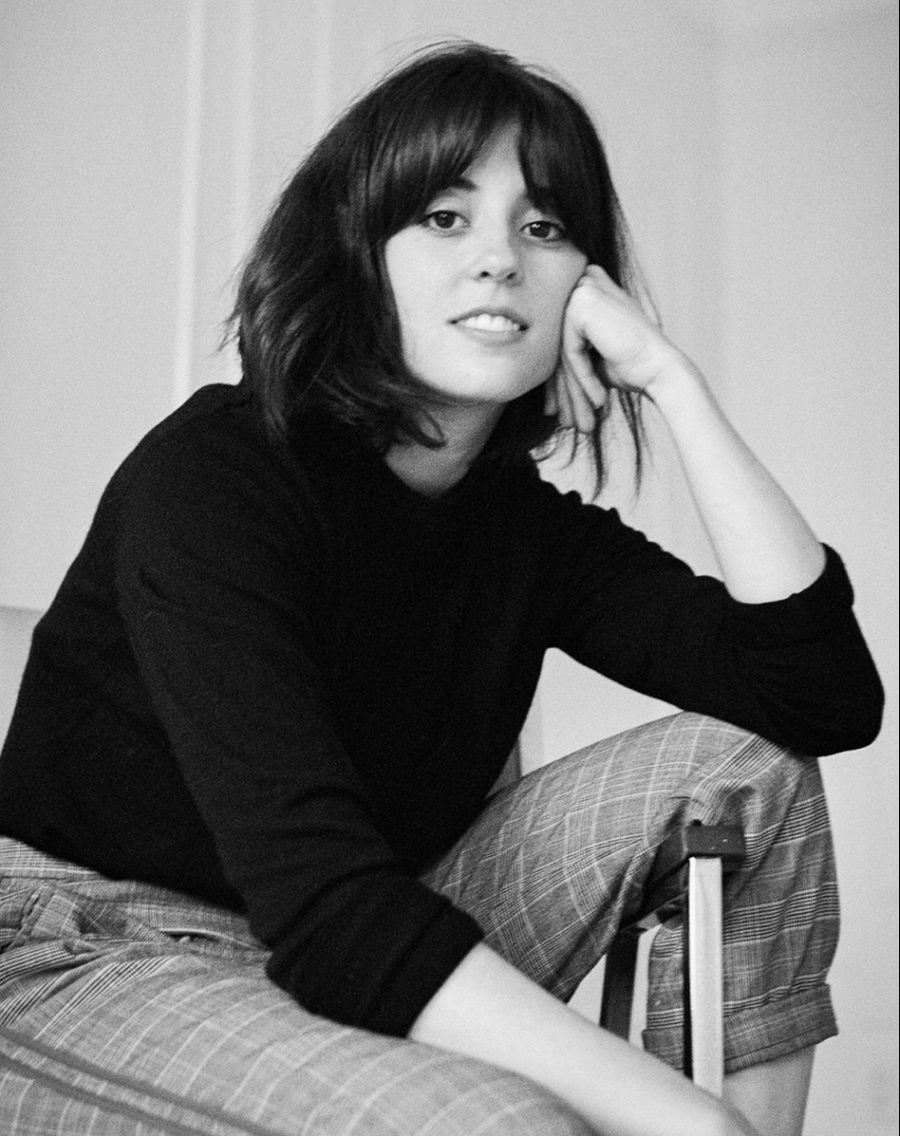

Kira Dane

Kira Dane is a filmmaker from New York based in Nara, Japan. She's interested in telling stories by digging for nuance in the overlooked corners of well-known topics, and often utilizes animation and experimental form in her work. Kira's film “Mizuko” was supported by Tribeca Film Institute, and she was a 2019 fellow of the Sundance Ignite Program.

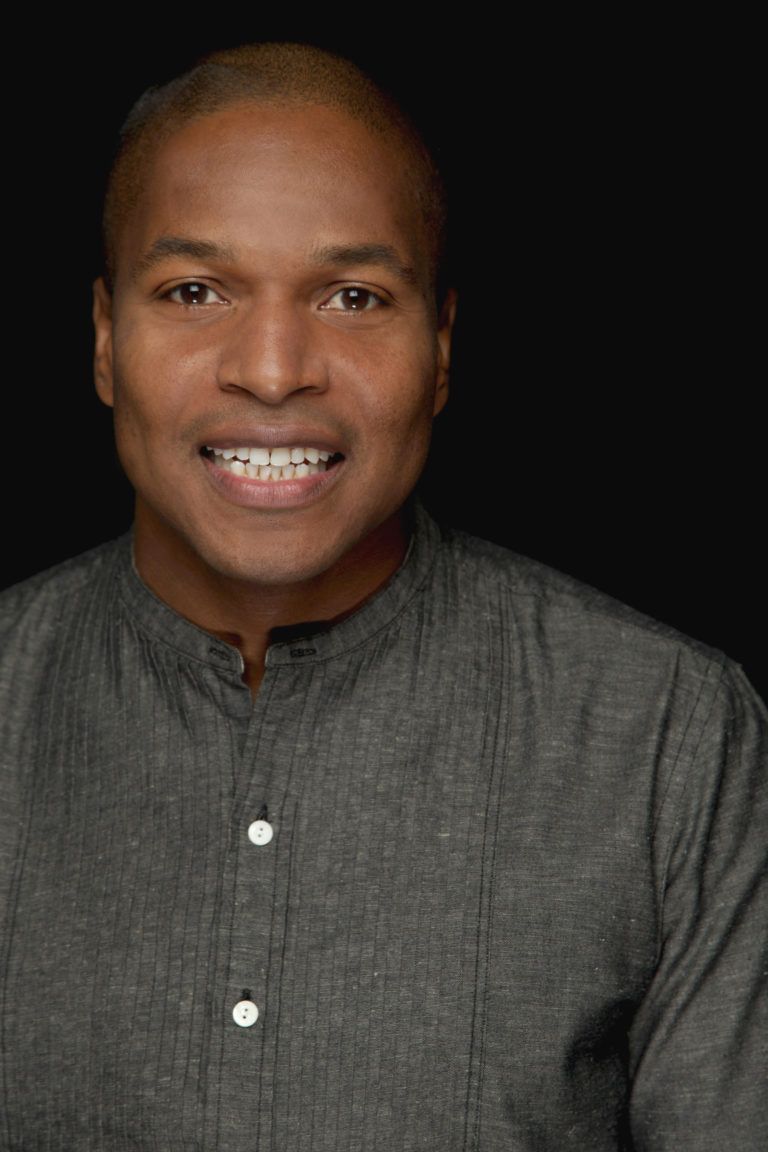

Katelyn Rebelo

Katelyn Rebelo is a Brooklyn based filmmaker. Her work sits at the intersection of documentary & experimental film, often exploring stories that reimagine concepts of femininity, politics, and personal freedom. She is currently a fellow at Jacob Burns Film Center, and her recent film "Mizuko" was supported by Tribeca Film Institute.