Rashaad Ernesto Green first fell in love with acting under the direct guidance of August Wilson, when he got cast in a reenactment of one of his plays at Dartmouth College. He went from feeling voiceless to being thrust into a magical world of theater, receiving a full ride to study acting at NYU alongside peers such as Sterling K. Brown and Mahershala Ali. But the moment he came out into the real world, his scope became very small: he found himself pigeonholed into auditioning for the roles of drug dealers and thieves. Wanting to reach a broader spectrum with his craft and create roles for Brown and Black youth, he decided to go back to NYU to become a director.

During his time there, he directed and wrote a number of short films that gained serious momentum from the eyes of Sundance and HBO. One of them being “Premature,” a short film about a young woman who gets pregnant in the Bronx and is forced to grow up before her time, made in 2008 and starring Zora Howard. Cut to 2020, when a film of the same title and starring the same actress is about to come out in theaters. After a successful festival run that started at Sundance and resulted in Rashaad winning the “Someone to Watch” Award at the 2020 Independent Spirit Awards, Premature, the film, is set to hit theaters Friday, February 21, 2020.

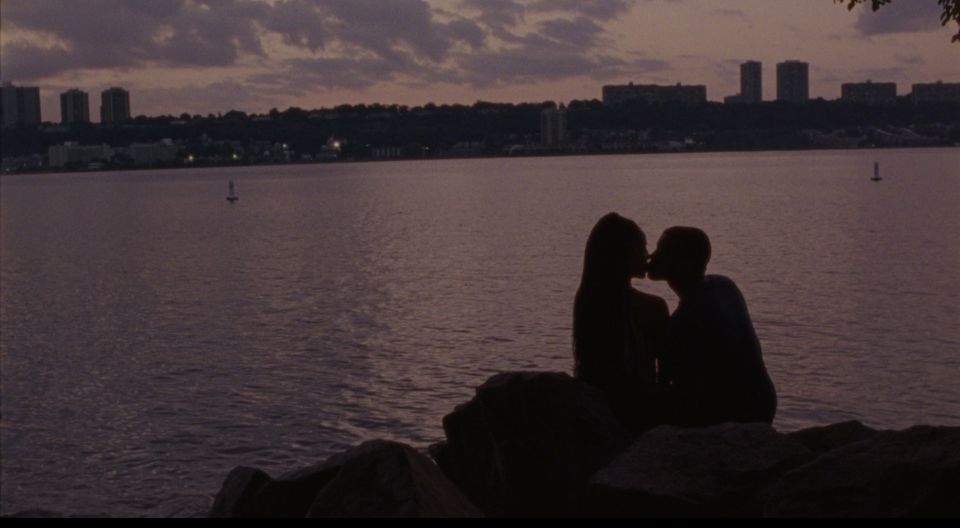

Rashaad Ernesto Green and Zora Howard, co-writers of Premature, asked themselves what they felt was missing in current day Black film. Feeling like there was an overabundance of Black victimization, pain, and suffering, they decided to tell a simple love story.

But fulfilling that void for the sake of art and posterity didn't come without sacrifice. After a steady and successful run as a television director for the past decade, directing episodes for Supernatural, The Vampire Diaries, and Vida, Rashaad had a tough choice to make. No production companies would sign the check for Premature, so he decided to green light the film himself with the help of classmates from NYU, CineReach, and Kodak. The decision required saying no to stable income for over a year, and taking a big leap of faith to tell the kinds of stories he wished existed. The film premiered in the Sundance Next section and, well, the rest is history.

FTW: What caused the shift from directing television to directing another feature film?

Rashaad Ernesto Green: No one told me that TV does not beget film. Film can turn into opportunities in television and film, but television does not turn into opportunities for film. I got into a cycle and routine, but didn’t realize that I was boxing myself out from opportunities to make more features. In order to make another feature, I had to go back to the drawing board and say no to any opportunity in television for over a year and a half. I went and finished Premature. It took saying no to guaranteed employment in order to do that. Of course when I said no to television, everything started pouring in. But that’s what it took—a leap of faith and knowing that hopefully TV would still be there when I turned around. And it was. Once Premature got into Sundance and people started seeing it, the TV offers just got better.

You’ve talked about how Premature was a radical act by telling a young Black love story, outside of themes of fear and pain. Can you expand upon this?

We didn’t want to offer more of the same. We understand why those films are made, especially during this time when Black bodies are under attack. But if every time we go to the theater, we’re made to feel like we’re victims and that we should fear each other or our country, it’s always tragic and oppressive. We can internalize those views about ourselves and our place in the world and what we have to offer. We learn about humanity and our representation in film.

Because of my journey from acting to film, I felt like I was auditioning for a certain type of role because it was the only role that was being presented to me and I also felt like I had a responsibility to create the stories that I wanted to see on screen. Black artists are being swayed by an industry instead of asking ourselves what do we want to see?

We feel influenced by the gatekeepers about what images are marketable and what images sell. What does that say when all of those images have us dying in the street? I just think that we have more to offer than that. There’s two ways to go about gaining empathy from people. One is to ask for sympathy because our lives are so different and look at what happens to us. But there’s another way to relate to each other as human beings. Sometimes that’s presenting stories that are universal, that regardless of color, we can all relate to. My hope is that even though Premature is very specific to Harlem and this culture, that when an older white woman watches this film, she can say that’s how she felt when she was 17.

Harlem is a rapidly changing landscape. How did you want to discuss this in Premature? And how did you go about capturing this time capsule of Harlem today?

I’ve lived in Harlem for 20 years and I love it. It has changed dramatically over the time that I’ve lived there. All the stories I’ve told thus far have been New York stories because it’s the world that I know. I try to shed light on parts of New York that are rarely seen on film, or not seen correctly. By shooting on film, I wanted to capture these beautiful young souls on celluloid, but also capture Harlem at a time before it changes to something that’s entirely unrecognizable. It’s gentrifying at an extremely rapid pace. Five to 10 years from now, it’s not going to look like the Harlem of today. I wanted to capture this moment in time on film.

How did you take inspiration and memories from Harlem and implement them into the film? How does one go about translating memories into scenes?

That’s our job as artists. We call from our life experiences and write what we know. Ask yourself what this human being wants and needs, and then hopefully you can bring your own experience to that character’s perspective. They might not know everything that you know now, but ask yourself where you were at that time in your life and what decisions you made that set you on a different course for the rest of your life. It’s my responsibility to write all my characters three-dimensionally. Fill each of them with my fears, love, knowledge, and wisdom. You try to wear that character’s skin.

Tell me a bit about your creative relationship with Zora. You have collaborated as artists for a while. How did this working relationship come to be and what works so well between you both as artists?

I was doing a show in Harlem right after graduating from NYU for acting and Zora had an internship there. When she was 12 years old, she put on a spoken word performance on that same stage and I was really blown away. When I decided to go to film school and wrote "Premature," I cast Zora because I was so impressed with her wisdom at her age. She was phenomenal and that short went everywhere. It won the American Black Film Festival, went onto HBO, and did over 80 festivals internationally.

She’s been an integral part of my life. Her family has been like my second family. We lived on the same block for the last 15 years.

Your debut feature, Gun Hill Road, came out in 2011, and Premature is coming out in February 2020. How have you changed since directing your first film?

When I made Gun Hill Road, I didn’t really feel like I knew what I was doing. Set life was very new to me. Everyone had so many questions and I didn’t always know what I wanted. Now when I walk onto a set, I know what every department does. I know what they should be doing, even if they’re not doing it correctly. I feel much more comfortable on a set now, especially having come out of television where everyone has a role that they’re getting paid for and their livelihoods depend on their performance.

Going back to independent cinema, where everything’s on a budget and you’re working with a range of experience levels—I maybe became a bit too comfortable with television and took things for granted. Premature was a bit of a wake up call. It was a bit rough around the edges, but once I got back into the swing of things it was really nice.

With Gun Hill Road, you said you felt like you overwrote scenes and I think that happens with a lot of early filmmakers. You really found this balance in Premature of letting things be silent when they can be. How did you learn to write that way?

I came from theater, which is very much about the language. Where in film, it’s about character and the actions that they take. Sometimes the action will be far more interesting when they’re silent than when they’re talking. When I made Gun Hill Road, I was closer in my transition from theater to film. I was very much in love with language. Now, I try to be very intentional and sparse. I’ve grown as a writer as a result of watching cinema. TV can also get very overwritten. Having directed many scenes that I felt were unnecessary, I understood that to be wary of that when approaching scenes.

Looking back at Gun Hill Road, I ask myself, do people really talk like this? Do we have monologues? With Premature, I tried to put myself in that situation. We often don’t tell people how we feel and we often conceal what’s actually going on underneath.

"When you’re asking your crew for favors, they have to understand why. The more you can involve your crew in your process and have a relationship with them, the better off you’ll be when you’re up against that final hour and you need your crew to go to bat for you."

TV is such a quick turnaround process and the crews are there for work, not solely to create your vision. How do you enter that situation without having insane imposter syndrome?

I try to have as much a connection with everyone on set along with knowing everyone’s name and asking people if they need help. It helps people feel like they’re in it for more than just a job. There are easier jobs in the world than working New York summers on film sets. The reason why they found themselves in that job is because they love film. That has to be true. You try to remind people of that.

When you’re asking your crew for favors, they have to understand why. The more you can involve your crew in your process and have a relationship with them, the better off you’ll be when you’re up against that final hour and you need your crew to go to bat for you. Listen to their concerns so that they have an ally in you. It’s important to think from the perspective of your crew. Does it feel like they’re a part of something? That their position is important in telling this story, and they're a part of a whole, not just putting in another day of work.

After high stress experiences in both TV and independent film, what are some practical things you’ve learned to stay clear headed and calm on set?

In television, there are a lot of people on your back and they’re not people that you employed. You’re being employed by that production. You’re a guest in someone else’s house.

I’ve been introduced to a whole bunch of situations, so I’m able to be more flexible. I know how to tell something’s a problem earlier. I know certain personality types right off the bat. If I need to fire somebody, I try not to wait until strike three. You have to set the tone and you have to set it early. I’m not afraid to do that anymore.

What is your best piece of advice for aspiring directors?

It’s a grind. You have to believe in yourself because there are going to be times when you’ll ask yourself if you made the right decision in becoming a storyteller. You will second guess yourself because of how life is, how your career turned out, or the pace of your trajectory. You’ll ask yourself if you’re ever going to get another opportunity, if you have what it takes. Rather than silencing these voices of doubt, you have to learn to act in spite of them. You still have to get up in the morning and listen to the voice that’s telling you that you need to tell your stories.

There’s an entire industry made up of people who are able to buy homes and yachts based on your talent. There’s a whole lot of people who point at you and tell you what you should and shouldn’t do. They make money off your voice. I encourage you to not be silenced by those voices but to press forward in spite of them. A lot of the films and television that are made, you’re very capable of making yourself.

There’s not a lot of people that are lining up to take a chance on you. You have to take a chance on yourself and show them what you’re able to do before anyone takes a chance on you. That doesn’t mean settling, but adjusting. Don’t wait for people to take a chance on you. Don’t wait for miracles. Sometimes you have to make miracles happen.