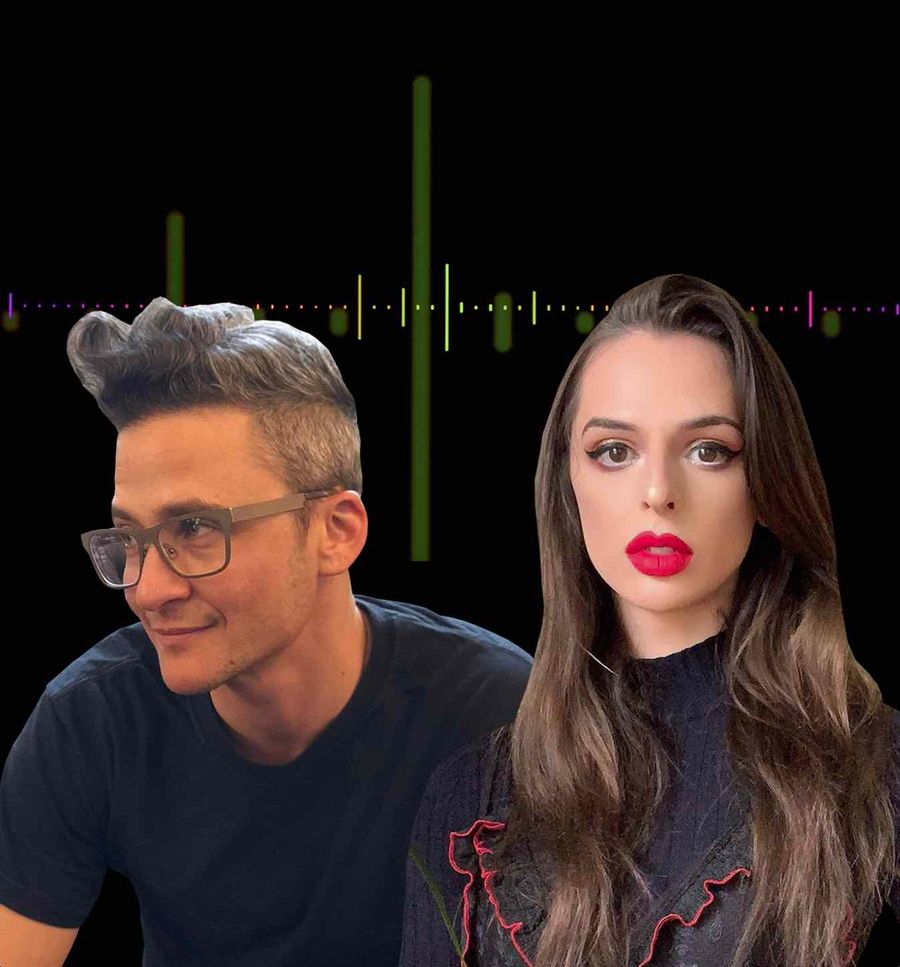

Photo credit: Kase Pena

For this special FREE THE WORK podcast miniseries, "The Future, Through Our Eyes," watch our FTW Community Lead, Chloe Coover, sit down with trans, non-binary, and intersex creators making waves in the industry.

In this episode, sit in on our conversation with Kase Pena, who recently made history as the first Transgender Latinx Woman to get hired as a Staff Writer on a scripted TV show when she joined the Brujas writing room created by Showrunner Tanya Saracho. She’s also the first Trans Latinx Female to join the Writers Guild of America. Together, Chloe and Kase talk about creating legacies of positive trans representation, mentoring emerging trans talent, and Kase's exciting projects in development.

You can watch our close-captioned video or listen to this episode through Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, and Soundcloud. Keep scrolling for the full transcript!

After the episode, head to alliesinarts.org to support Kase Pena's Trans Los Angeles.

Kase Pena

An award-winning filmmaker, Kase was born in New York City. She’s a Transgender Latinx Woman, the offspring of working class parents from the Dominican Republic, and she’s fully fluent in Spanish.

She’s the first Transgender Latinx Woman to get hired as a Staff Writer on a scripted TV show when she joined the Brujas writing room created by Showrunner Tanya Saracho. She’s also the first Trans Latinx Female to join the Writers Guild of America.

Earlier this year, Kase shadowed Emmy Award winning Director/Showrunner Joey Soloway on the set of Transparent Musicale Finale. Further, Kase has been the recipient of some of the most prestigious Fellowships in the industry, including The Latino Lens Narrative Shorts Incubator; Film Independent Project Involve, among others. Sony Pictures Entertainment named Kase their Diversity Fellow for 2019. HBO has picked up distribution rights to Full Beat, Kase’s latest short film. Along with her short film Trabajo, this marks the second time HBO distributes a film written and directed by Kase Pena.

Regarding her interests, Kase is mostly inclined in relating powerful human stories. Some of her favorite films and TV shows include: Do The Right Thing; Mean Streets; This Is Us; John Ridley’s American Crime and Breaking Bad.

Chloe Coover

Chloe is FREE THE WORK's Community Lead. She's an artist, quadruple Leo (Sun, Moon, Rising + Mercury), ANTM scholar, meme enthusiast, and is proud to be a woman of trans experience.

CHLOE COOVER: Hi, I'm Chloe Coover, Free the Work's community lead. And today I'm joined by New York-born, Los Angeles based-filmmaker, Kase Pena. Kase Pena is the first transgender Latinx woman to be hired as a TV writer on a scripted TV show. And the first trans Latinx female to join the Writer's Guild of America. Congratulations. She shadowed Emmy Award-winning director slash showrunner Joey Soloway on the set of "Transparent Musicale Finale" is that how you say that?

KASE PENA: Um hmm.

CC: Okay, I've seen it written but then, and has been the recipient of some of the most prestigious fellowships in the industry, including The Latino Lens Narrative Shorts Incubator and Film Independent's Project Involve, to name a few. So thank you so much for joining us over Zoom, getting to hang out with some distance.

KP: Thank you for having me. Thank you Free the Word, thank you Chloe.

CC: Yeah.

KP: This is very, very important stuff that we're doing here.

CC: Yeah, I was really, so we've met before and talked, and I was really excited to bring some of the conversations that we've had previously into a more broad, sort of public forum. So I was really interested in starting off with a discussion of "Full Beat", which is the short film that I first was introduced to your work through. So for the audience that hasn't yet seen it, can you talk a little bit about what "Full Beat" is about and where they might be able to view it, et cetera.

KP: Well "Full Beat" is a 10-minute short film. It's about a transgender youth, who has to spend court appointed time with her dad. Her parents are divorced, and her dad comes to pick her up for the weekend, and she doesn't wanna go with the dad because at home, with her mom, she's free to be herself, she's free to express her femininity, while the dad doesn't want any of that. And he wants to control her, and he wants her to be the person that he wants her to be. So she doesn't want to go, but at the end of the day, it's not in her control, and so she has to go, and she ends up finding an ally in the dad's new girlfriend. Like I said, it's a 10-minute short film, it's very quiet, it has very little dialogue, it's a lot of, the communication, I used a lot of body language, because it's something that I don't see a lot in a lot of films. And yeah, it's gotten me a lot of, I mean, it's gotten a lot of praise by a lot of people, and people can currently watch it on HBO. The reason I made that film is because, as a trans-identifying individual, I tell stories that no one else can, that's a fact. That's not me, that's a fact. And I've never seen, most of the stories of trans people that I've seen, first of all have been told by non-trans people, and they all center around the same three, four things, prostitution, drug addiction, or the transgender girl or woman gets kicked out of the home, or the parents don't want her. And I don't tell those stories, even though those are realities of our community, I tell stories of, for instance in "Full Beat" there's none of that. There is conflict between the dad and the daughter because without conflict you can't tell a story, but she's not a drug addict, she's not a prostitute, you see the presence of her parents. Plus when have you ever seen a film about a 17-year-old transgender Latinx girl who's in the lead of a film? So that's where I come in and I tell these stories that no one else, it's not that no one else is telling, in all honesty, if we're gonna be very honest, and that's the one thing that I appreciate about you, that you encourage me to be honest always, other people can't tell these stories, that's why they're not telling them, it's because they cannot tell them. That's just the honest truth.

CC: And obviously there's specifics about lived experience that make certain things possible and impossible, but how would that story look, do you think, if it was framed through a lens of someone else who was telling it? If it came from anywhere other than from your point-of-view, how do you think that that story would be told?

KP: I don't know, because I'm not someone else. So it's almost impossible for me to answer that question, but one thing I can say is that the films that I've seen about transgender people, when they're made by non-trans artists, there's a lot of eye rolling.

CC: Totally.

KP: There's a lot of eye rolling 'cause there's a, "Well they didn't get that right, "or they didn't get that right, "or they did that because it was a convenience to them." I've had cisgender people read my screenplays and one note that I got one time from a lady was like, "Wow, I was really rooting for your film, "I really wanted to like your screenplay, "but you wrote it for transgender people. "I was hoping you had written it for us." I'm like, "What do you mean? "Yeah, I wrote it for transgender people, "why am I gonna write a film about a transgender woman, "and I'm a transgender woman, and I'm writing it, "in my mind," I'm like, "I have to make sure "that cisgender people like this." No, you don't have to like this.

CC: Well the other thing too is there's so much of film that's been made that's not for us, that expects trans people to see themselves in narratives that don't center our experience. So it's kind of interesting, because in a way, films like the ones that you're making, and other trans artists are making, are encouraging cis audiences to start doing some of that work that we've had to do in our experience of cinema. It's worth getting into a practice of putting yourself into characters that you don't see yourself in necessarily.

KP: Of course, and a lot of things are changing, thankfully. We are very excited about the changes, but there's a lot of work to be done still. Let's tell the truth, there's a lot of work to be done, but we're not waiting for the work to be done, there's so many of us out there today who are just taking matters into our own hands, we're not waiting for people to green light our movies. And we're telling our stories the way they should be told, and more people are paying attention to them, and I discover every day that more people are wanting to watch our movies and learn what it's really like to be a transgender man or woman, because oftentimes when we just utter the word transgender, so many people automatically think transgender women. And it's important to highlight our transgender men, our brothers, because their narratives too are often forgotten.

CC: Yeah. I'm interested in going back a little bit in what you were saying about the changes that you've seen. In the course of time that you've been pursuing a career as a filmmaker, what have some of the shifts been that you've observed, both in audiences and in terms of people behind the scenes when you're pitching? Have there been significant changes?

KP: One change that I've seen is, I wrote a film, I've been a filmmaker first of all for a long, long time, I tell people that. We now hear about transgender stories, we see more and more transgender characters on television, and I tell people that I've been a filmmaker before it was cool to be transgender. When our stories were not being told, when people did not wanna hear anything that has to do with transgender. And actually I've been a filmmaker when people would've fired you for being trans, had you come out as trans, people could've fired you. I used to work on sets, and I was working on sets before I came out as trans. And I know for a fact that there are a lot of people back then, that had I told them I was trans, they would've not hired me. Maybe they would've not fired me, but they would've stopped hiring me. And I also know there's a lot of people who would've been totally okay with it. There's always that as well. So one thing that I've seen is that, going back to what I told you a little while ago, was the note that the person, the executive gave me, that said, "I was really rooting for your screenplay "and I wanted to like it, but you wrote it "for transgender people, and I wish you had "written it for cisgender people," that's a note that today, I think, people will be a lot more intelligent not to give. That note was from five, six years ago. So that's one thing that I think a lot of people are a lot more careful to say things like that.

CC: So it's not necessarily that they know better, necessarily, in terms of their actual understanding, but they know not to say certain things.

KP: But there's still a lot of problems, because I have, for instance, I have people who wanna help me, who respond to my work, but I still get these notes sometimes. And mind you, whenever I write something, I'm always dealing with cisgender people, there's not a transgender executive, who's green lighting movies. So at the end of the day, regardless of what I do, I have to encounter cisgender people. And most of the stories that I write, I'm writing stories that are based on lived experiences. And one note that I often get is people telling me, "I liked your script, I think it's beautiful, "I think it's this," and then when the notes start coming in, they're like, "What I wanna see is, such, and such, and such." And that's a problematic note, because I'm not writing what you wanna see, I'm writing my experiences. And if what you wanna see is not something that happened to me, how can I possibly add that, take your note, and make it a part of my film? My film is no longer gonna be truthful. So that's a big problem, because I'm not writing what you wanna see, I'm writing what I've lived. Now the day you pay me to write a screenplay based on, I don't know, on a book, or whatever, an idea you have, you have every right to tell me, "What I wanna see is this, this, and this," because at that moment, you're paying me, I'm working for you. But when I'm writing a screenplay on spec, and for those who may not know what spec is, spec is short for speculation, and that means that you're writing, not getting paid. No, I'm not gonna write what you wanna see. I'm writing what I wanna see, how 'bout that?

CC: Totally, and the thing is, I think there needs to be more of an understanding that what you want to see, there's going to be other people out there who want to see exactly that too. I know personally, I want to see what you want to show your audience, I'm part of that audience, I'm definitely down.

KP: Thank you.

CC: So I think that hopefully there is a growing consciousness that there is more of an audience that's out there for, and even if it's not other trans people, I think there's an audience out there who just wants to hear stories told that feel authentic to lived experience, period, point blank.

KP: Absolutely, and in order to be very clear, that it's not just for transgender people, that's for every group that has been kept outside of Hollywood for ever and ever. Every group wants to see stories that are real to them, written and directed by members of their group.

CC: Yeah, totally.

KP: Every group.

CC: Yeah, the thing that you were saying about executives and those who are in the position of green lighting is very important, and something that I don't think people has as much visibility into as probably they should. If we're wondering why there are these barriers for filmmakers of any underrepresented community to go through to get their stories told authentically, it's because the people that are in the position of making them don't reflect them. And that's a real problem.

KP: And I would love, love, love, love, love, love to see everyone, the organizations that give out grants to filmmakers, to independent filmmakers, there's a lot of them. Some of them are small, some of them only give grants of 2,000, 3,000, some give grants of 30, 50,000. So all grant organizations, would love to see the film festivals, they're so influential in people's career, and introducing a filmmaker to the industry. The writing programs. If you're going to support a story about a transgender person, please let it come from a transgender artist, because we have seen too many of our stories be told by non-transgender artists. At some point, we must be allowed to tell our own stories. This is not difficult to understand.

CC: Yeah.

KP: And I found a link, I was doing some research, this was about a year, a year-and-a-half ago, and I found a link somewhere, and it listed, I think it was 10 to 15 films about transgender people. And every single one of those films had been written and directed by a person who's not trans. So, whenever I bring up this point, a lot of people look at me like, "Well what do you mean? "It's totally fine that other people should be writing." No, it's not totally fine.

CC: It's dangerous actually.

KP: It's actually dangerous because think about it, 50, 60, 75 years from now, when you have a 16, 17, 18 year old transgender girl, who wants to watch old films about us, they're gonna go back in time and every single one of our films is written and directed by a person who isn't trans, who isn't getting our narratives 100% straight, that's a problem. That's a problem. Whenever you have a group of people tell the history of another group of people, that creates a problem.

CC: And the thing too is that so much of what gets put into media has such a visceral impact on the lives of trans people. For example, trans people, among any other marginalized community. So the way that we're represented on screen really does have pretty direct correlation to how people are gonna treat us as we move through the world.

KP: Of course.

CC: It's not just sort of entertainment, or this casual thing, it really has some serious repercussions.

KP: No, it's not just entertainment, because the problem with belonging to a marginalized community is that, for some reason, when you belong to a marginalized community, the only stories you're allowed to tell from that community are real dramas. You're never allowed to tell a science fiction movie, or an action adventure. Why can't we have an action adventure with transgender people? 'Cause if there's anybody who knows about adventures, it's transgender people.

CC: Right!

KP: Yeah, fantasy, magical realism, romantic comedies. But every marginalized group is always, every time we tell a story about this group, it has to be like this intense drama, because we can't tell a comedy. I wanna see a transgender character like I see in some other movies, where you have a character that is weird, and quirky, and funny, and eccentric. And it's totally fine, and people love that character. Why can't we have a transgender character like that? Why does it always have to be that our stories are set off by trauma?

CC: That's a really good point.

KP: We get bullied, we get beaten at the end.

CC: And to me, honestly, to have a fixation on telling those kinds of stories is encouraging the world to repeat those stories. So if we're centering trauma in the trans experience and we represent it on screen, we're just encouraging the world to reproduce trauma for trans people in the future. So it could be, there's not sort of blameless to look at media that does that and assume that that has no effect. And I really would love to see, for example, what you would, if you were working on a, for example, a period piece film, or a fantasy film, or magical realism, any of these other genres, I would love to see what your perspective would be on any of those other realms that are not usually offered to trans creators.

KP: Of course, and I also think that if, when I get hired to do a big action adventure movie, then in the same way that non-transgender people have made our films, we should be able to direct cisgender people.

CC: Totally.

KP: Totally, 100 million percent. I am excited though, 'cause for instance, I have a screenplay called "I Love Hate," which is based on a lot of things that I went through as a transgender person who's from the Bronx, New York, and this is when I was younger. So the character is younger than I am now, but I have found a producer, he is cisgender, he's family because he's a gay man, he's Latinx, so he's a person of color. He was born and raised in LA, but his mom was born and raised in the Bronx, New York. So he grew up listening to his mom telling him stories about the Bronx, New York, so he always felt this connection to the Bronx, New York, and that's where my story takes place. He also went to NYU when he grew up, and then he lived in New York, I think, six years after graduating, so he spent about 10 years in New York City. So he understands the story that I'm writing. He's gotten behind me a million percent. If there's someone who can raise money to make that film happen, and we're looking for $1.5 million to make that film, he's definitely it. So, what I'm saying with all of that is that there is change coming, so it's not all gloom. It's not all bad. There is a lot of hope, and we're excited about that. We're pointing out things that have transpired in the past. Today, I'm excited because someone like me has a chance to make a film, more than say, 15, 20 years ago.

CC: Totally. And what gets me really excited, personally, I really wanted the focus of these conversations, as part of this whole series to be very future forward because I get so frustrated sometimes with almost feeling like I'm forced to respond to a very negative past, when I would rather look forward at a future that does offer opportunities for people in a more equitable way. So, I really like to think about the next generation, how the world that we're working to create is gonna foster this next generation of trans talent. And do you see pipelines being created for emerging trans talent?

KP: No I do not, I do not.

CC: I wish we did.

KP: I, personally, it's been a passion of mine for a long time. I am hoping to find, at some point, I can't do it at this moment, but I'm hoping to find, but I'm being very intentional about this, and I'm hoping to find a young transgender talent who really wants to be a filmmaker, 'cause I can't force you to wanna be a filmmaker. I've tried to talk to a couple transgender people, like, "Hey, would you like to be a part of this?" And they're like, "Yeah, yeah," and it's fine, they don't have to respond, there's something else they're passionate about, so that's beautiful. But if the passion doesn't lie within you, then how can I possibly take you under my wing? But I'm dying to find that young transgender person so that I can take her under my wing and train her to write, and train her to direct. And not just have her shadow me for two weeks and then be like, "Okay, you shadowed me for two weeks. "Bye, you're on your own. "Go figure it out." No, I wanna put a year or two years into training her, and actually actively be seeking opportunities that would give her an opportunity to write and direct.

CC: That kind of investment is so important for people to get their foot in the door.

KP: Absolutely, and for someone like me, that person never existed when I came up.

CC: Right, I was gonna ask actually if you had had any mentors or anyone who helped you?

KP: No, I've had mentors, I've had mentors, and I've had great mentors, and I am so grateful to them. I adore the people who have mentored me and I respect them, and I admire them, and nothing but love and gratitude. But at the end of the day, there's nothing like having somebody just like you mentor you. And the thing is that none of those people are transgender, so that element was always missing. Again, they're beautiful, a lot of these people I'm still in touch with them, a lot of these people I can reach out to them and ask them for help and they'll be there for me. So thank you, thank you so much. I wanna be able to train a transgender girl, and possibly a transgender man as well, but first, a transgender girl because it's what's closest to me, right? I never had that, I never had a transgender mentor, writer, director take me under their wings, because I don't even know that that existed when I was a filmmaker, when I was coming up the ranks.

CC: Right, and I mean, if it did, were they out?

KP: Exactly, they were probably around, but they weren't out, so I didn't know to go to them.

CC: Yeah. And I think that, it was interesting when we were initially hoping to broaden our pool of trans talent on Free the Work, and really do some concentrated onboarding and expansion of our community, there was a part of me that was like, "I know so many trans creative people "who are extremely brilliant, creative individuals. "I think that being trans is a creative act "in a lot of ways. "So they go hand-in-hand." And yet, there are so few trans people that I know who really have ever had anyone tell them that's something that they could do.

KP: The thing with me, I've always been an artist. I wasn't a filmmaker, but I've always been an artist. I drew before I could speak, and I remember when I was in first, second, third grade, I used to draw and I used to sell my drawings for like a dollar in school to other kids. So I was always an artist, and I was always looking to make money off my art. Being from New York, I've told people this many times, that graffiti was all around me, so that's a big influence on me. So I wasn't a graffiti artist, but I was around a lot of graffiti artists, and I've always paid attention to colors, and shapes, and combining the two. My mom was a seamstress who created art with her work. So I've always expressed myself artistically, but later on, I never knew as a child, I never knew when I was 12, 14 that being a filmmaker was ever a possibility. But then as I got older, and I learned more, and I heard, "Oh this person is a filmmaker, "this person is an independent filmmaker, "Spike Lee is an independent filmmaker." I remember the first time I heard that name, Spike Lee, and that he had made a movie. That's when my eyes started opening up and I was like, "Whoa, wait a minute, "I can focus my art specifically into this," 'cause my art back then was all over the place.

CC: Totally. I think, yeah I was actually curious to ask, there were two things in what you were just mentioning that I was really curious about. So in two different directions, whichever one is most interesting first, I really wanted to talk about the sense of place in your work, and your career. So as coming from the Bronx initially, how did that shape your work as an artist? And then living in Los Angeles, what has that done to evolve your work and shape your work?

KP: I went to this really small film school called CCNY, which is the City College of New York. And everything happens for a reason. I tried to go to NYU, I wanted to go to NYU, but I couldn't afford it. So when I couldn't afford it, I felt like my dreams of attending film school were shattered until someone pointed out, "You know, "there's a really good film school "at City College of New York," and at that time, City College was much cheaper, and I was in a position where I could afford it. So I was accepted, I applied and I was accepted, and I realized the classes were kept very small, we had 12 students per class, we had great equipment, the highest quality equipment. Where later on, I saw kids from NYU coming up to my school, trying to get the equipment that we had.

CC: So you're like, "Cool, made the right choice."

KP: Right, through one of the students of City College, they're like, "Hey, let's take the equipment out "and we'll say it's for you, but it's for," and I saw that a few times. The professors there were a bunch of rebels, independent filmmakers, documentary filmmakers, who told real stories. Before I went to film school, my film diet consisted of Hollywood films. So when I went to film school, I was under the impression that I was going to learn how to write "Terminator" or "Batman" "Godzilla" and that kind of stuff, because that's all I knew. They were like, "No, we're not doing that here, "you're gonna tell real stories about who you are "and the places you come from." And I was so confused when I first heard it, because I was like, "Wow, but who's gonna "wanna see something like a story from where I live, "on that block, where I live?" So they started showing me all these independent movies that had won major awards, and I completely bought into it, because the way those films made me feel, no Hollywood big budget movie ever made me feel that way. I started seeing these films, I started seeing characters that reminded me of my mother, my cousin, my friends on the block that I lived. Whether those films were made in Germany, China, or anywhere in Latin America. I started to really see myself, because when I watched "Terminator" and "Batman" I never saw myself, I just saw entertainment. So I started writing from that point-of-view, and I noticed that the difference between, I think this is something that is kind of disappearing, but the difference between being a filmmaker from New York, at that time, and being a filmmaker based in LA, is that in LA, I noticed that most filmmakers here were only interested in telling movies that made a lot of money. Because this is where Hollywood is. Excuse me. In New York City, most of the filmmakers were interested in telling independent films, real stories about real things, and these are films that, for the most part, get into big film festivals, win major awards, and so that was my influence, and that's how I arrived at this place telling stories like "Full Beat" writing stories like "I Love Hate." My new film, "Trans Los Angeles."

CC: Okay, I love that, yeah.

KP: Yeah, that I would love to share about that. But at the same time, we cannot forget that this is a business, and that we need to make money, I need to make money in order to sustain myself. So I want my career to have that balance of I make things for the money, which there's nothing wrong with that, but then I wanna always go back to my roots and go and make these little films that may not make a lot of money, but they mean so much. And I know they're gonna mean a lot to my community.

CC: Totally. And there's room for careers, and this is interesting too, there are, in the history of film, so many directors who have done that kind of balance, going between creating a smaller film, and then their big budget blockbuster, and then back and forth. But that's the kind of career mobility that so infrequently is afforded to women at all, and then to trans people, there's no real historical precedent for it. But I'm really excited to hopefully, fingers crossed, that we're moving into a new era where people like you can be the first wave of setting that precedent.

KP: Well I'm definitely trying. I worked really, really hard over the course of many, many years. And I'm still fighting to be recognized. I've been getting recognition, and so I'm grateful, but I'm still fighting to get more recognition, and so yeah.

CC: Yeah. So just to circle back a little bit, I wanted to talk about the, is it "Trans Los Angeles"?

KP: "Trans Los Angeles".

CC: Yeah, so that's, what stage of development is that in currently?

KP: Well I wrote a script, it's ready to go, it's ready to go because I'm saying it's ready to go, I'm not sendin' it, this is not a screenplay, I've been very clear about this, this is not a screenplay that I'm sending out to companies, I hope to get the money. Because I wrote a screenplay called "I Love Hate", going back to "I Love Hate", in 2013, and it's 2020, and I'm just finding a person today, seven years later who's like, "I'll get behind your movie, "because this is a very important movie, "and I see your voice, and I see how real "this film is, and I see that nothing's been done "in this industry like this, "especially by someone like you." So it took seven years to find that person, we're still looking for the money. But I told my managers, "I am going to write a movie "that I can just pick up a camera and make a film, "and I'm not gonna ask anybody for permission." And they sent that script out to people, and it's gotten me meetings, and that's beautiful, but like I keep telling people, "I'm not waiting for anybody," I'm not, because look at what happened with that other script, I'm still waiting, seven years later. So, "Trans Los Angeles" I wrote it precisely so that I can be free to tell the story. I know when my story is, I know that my script is, I know it's tight. That's it. I was trying not to be, but hey, it is what it is, I know my story is tight. I've been a filmmaker for a long time. I know what I'm doing. I know what I'm doing, and people sometimes, when you send your script out, there's always but, "Oh I like it but," "Oh I like it but," and I'm not tryin' to hear but.

CC: So you're trying to make it without compromising the vision.

KP: Without compromising the vision, and without having to ask for permission. So I still need a little bit of money, going back to "I Love Hate", that's a screenplay that the way I wrote it, you can't just, "Let's do it with an iPhone," it can't be done. So we need that $1.5 million. This one I wrote it, and I can shoot it with $50,000, I can shoot it with $100,000, and I designed it in a way that I'm making it very easy for myself. And the way I did it was, "Trans Los Angeles" the reason it's titled "Trans Los Angeles" is because it's anthology of four short films. These short films are standalone, meaning the stories don't intersect. I wanted to be very careful about that, because whenever you have these films where four, five short films that make up a feature and the stories intersect, and the ones that I've seen, for the most part, it kinda seems like, "Oh how convenient," that all these stories converge at the end. If it's a comedy, it works great, but if it's a drama, if you're writing something real and I know these trans characters, I know these stories are not going to intersect. So no, the stories do not intersect, because that's a question I get a lot. "Do the stories all come together?" No, they don't.

CC: But there's a precedent for that in anthologies.

KP: Right. It's an anthology of four short films, each of the shorts is roughly 20 minutes long, and they feature a transgender character in the lead, and they all take place in a different area of Los Angeles. So one takes place in East Hollywood, the lead for that is Carmen Carrera. I also have Stephanie Beatriz of "Brooklyn 99" playing a character in that. Another one is a black transgender woman, girl, that story takes place in South Central. Another one is a Latina transgender woman from El Salvador, who has crossed the border without, she's seeking refugee asylum, and that story takes place in Boyle Heights, and it's told all in Spanish. And the other one it takes place in the San Fernando Valley, and it's the story of a white transgender man. And the reason I'm doing this is because I want to show, oftentimes when I talk to people, people think that transgender is one size fits all, and what I'm doing with these films is I am showing that there's a lot of diversity within the transgender community. And I am only showing you guys four different versions, but I'll be the first person to admit that I'm not even beginning to scratch the surface of the true diversity that exists within the transgender community, because I don't have a transgender elderly person, I don't have a transgender person from the Middle East. So there's so many more stories out there from other points-of-view. But at the end of the day, I can't tell a 12 hour movie.

CC: Right. But the goal, hopefully, is that in this new future that we're moving into, ideally fingers crossed, it won't have to just be you and a handful of other people telling those stories. That elderly trans person, someone else can make a whole other film about them, the trans woman from the Middle East can have a whole anthology about other trans people from the Middle East.

KP: Absolutely. And when I first wrote it, I wrote it as a feature film, I was writing this as a feature film for myself to make, no money, I'm not asking permission, I'm tired, rightfully so. I have the right to be tired. And while I was coming to the end, I had written three of them, and I was working on the last one, I had this moment of, "Whoa, wait a minute, this could be a television show." And so I was like, "Okay, well let me put "that over here, and let me just finish writing it, "because I'm not just gonna throw away what I've written." And so the few people that had, like my managers one day read it, that was a thought, "Have you thought of this as a television show?" I was like, "Yeah." And so a few people gave me that idea, and it's been, I'm working on the television version of it. I don't know what that's gonna look like, I don't know if the same characters I have in the feature are gonna be in the, I don't know what it was gonna look like, but I am hoping that it is also a television show. But doing the film, I trust that it's gonna get into a lot of festivals, I trust that a lot of people are going to respond to these stories. These are very slices of life films, that people are going to see the potential for this to be like, "Wow, this could be an amazing, "beautiful television show."

CC: Yeah. I can't wait. From that description, immediately that was where my brain went, I was like, "Oh yeah, I could easily "see that just expanding outward." I think we have to wrap up, but this was so great talking to you.

KP: Thank you so much, you guys are always so supportive, and so yeah.

CC: We try. We're big fans of everyone on the site, and you in particular for sure.

KP: Thank you, thank you, you guys are not trying, you guys are doing, which is different. Thank you, I'm here, reach out any time. I just wanted to say that "Trans Los Angeles" is a labor of love, it's a film that I am raising money for it, so if anyone out there is able to donate, I understand it's a very difficult time and a lot of people have gone without work, but if anyone out there is able to donate, and if anyone out there cares to see these stories be told by the people that should be telling them, you can go to www.alliesinarts.org and donate to my project, Kase Pena, "Trans Los Angeles" and I can send you the link if you wanna share it at some point with people.

CC: Yeah, we can share it, totally.

KP: Thank you, thank you very much. Thank you.

CC: Nice talking to you.

KP: Bye.

KP: Bye.