In 2017, we interviewed writer-director Minhal Baig, who had recently written and directed her first short film "Hala," the story of a Muslim teenager who struggles to reconcile her personal desires with family obligations. Since then, Minhal used this short film as the basis for a feature-length version of "Hala," which premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival and was acquired for worldwide distribution by Apple.

In the past year, Minhal also wrote an episode of Hulu‘s Ramy and, most recently, helmed a crew led by women in key crew positions (such as the DOP, Camera team, PD, Costume, Hair, Makeup, Composer, First AD, Colorist, Set Photographer, and Producers) for a PSA featuring Lena Waithe for MTV. “Save Our Moms,” examines the subject of infant mortality, a health crisis affecting African American women in the United States. We connected with Minhal again to learn about her experience of making the PSA.

Since we last interviewed you in 2017, you have directed a Sundance-premiering feature film Hala and recently directed the PSA, “Save Our Moms." How was your experience working in the commercial world?

Minhal Baig: I’ve always wanted to be a narrative filmmaker. I worked for a director at Smuggler very briefly a few years ago and got a little insight into the commercial world, and while I was drawn to it from afar, I was never really interested in doing the kind of work that people suggested I do in order to get jobs.

I approach filmmaking from a story perspective first, and I’ve never directed anything as a spec or just to have a job or make money. I’ve been very fortunate to have a career in narrative filmmaking. All the short films I made were stories that I felt very personally invested in. Of course, after Sundance, I was definitely curious about exploring the commercial world. When Hillman Grad approached me with this PSA, it was such an obvious fit. It was a cause that all of us got behind really quickly, and working with Lena and her team is always a joy.

The MTV and Viacom team really gave us the freedom to make this our own. They trusted our vision for the project but also brought in some great research and insight from the partner organizations they were working with. They were a terrific presence on set. From a filmmaking standpoint, it just felt like we were making a short film. We did have some specific beats to hit in the spot itself, and had an on-set doctor to make sure that the symptoms were being portrayed accurately. I had a lot of creative control on this project, but from the very start, this PSA was a really special production experience because all of my collaborators were approaching the project with such care toward the cause.

"I was shocked to learn that black women were three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy–related complications than white women . . . "

These last few years, more news outlets have brought awareness to mortality rates of black women as it relates to childbirth. How did research inform how you portrayed this phenomenon?

When the clients and the producers got on the phone, we had an initial conversation about how black maternal mortality is a huge issue that people don’t really know about. I was shocked to learn that black women were three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy–related complications than white women, and that the maternal mortality rate in the United States was far greater than any other developed nation. The factors that inform this figure are incredibly complex. We knew that the spot had to touch upon some of these factors but also provide an actionable item for viewers. We didn’t want to condemn the medical community or pregnant women.

Instead, we wanted to empower support networks—friends, family members—to continue to support pregnant women in their lives. Those calls to action were developed by the research that various partner organizations, including Black Mamas Matter, had done in concert with MTV and Viacom. We wanted to make sure that we visualized the missed opportunities for interventions and the interventions themselves.

In "Save Our Moms," your audience is transported through multiple moments in time. We see a happy couple in the first stages of the pregnancy; here, the tone is light and imbued with a sense of happiness. Closer to the lead character’s delivery date, the tone gradually darkens, suggesting a turn of events. What inspired how you used sound as a way of telling this story?

The turnaround for the spot was fast. Jesi Nelson, our composer, came on board during prep. We had her start generating ideas before she had seen any footage—just based on the treatment itself—because of our compressed post-production timeline. I had listened to Jesi’s work at Sundance and knew that she had the right sensibility for the project. She had a few ideas that helped make sure we weren’t too heavy-handed as we tracked April's pregnancy journey.

In my visual research, I watched a lot of different commercial spots and recognized that a familiar classical piano was used over and over. I wanted our spot to look and sound different. For those reasons, we used vocals for a warmer, more human approach to the score that fit the visuals. It was important for all of us that we end in a place of hope and action, so we circled back to those uplifting vocals at the end.

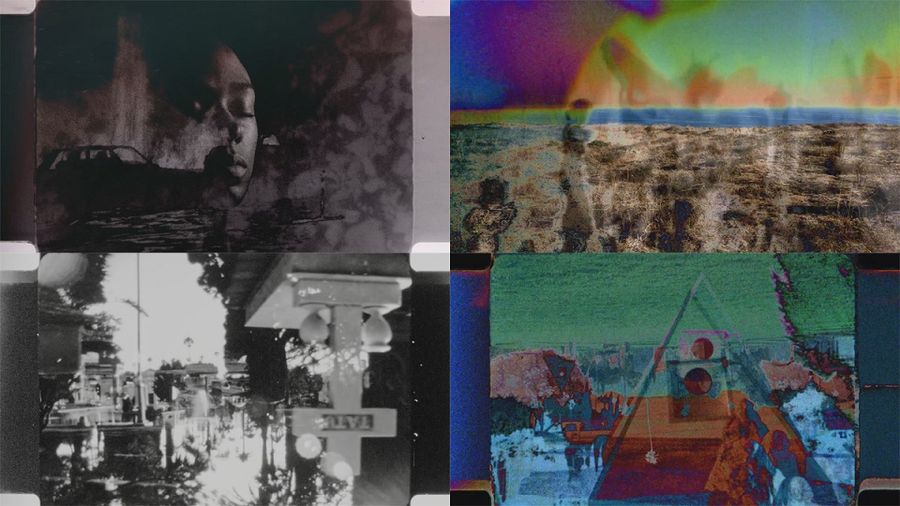

Jesi adapted the score to fit both the longer, 90-second version and the 60-second cut. In our sound design, we wanted to layer in the sounds of life and really make April and Jermaine’s world feel alive. We also really pushed sound design in the scene where she’s in labor for the first time; this is a moment full of anxiety and dread. We didn’t want to play it out explicitly on-screen, so our sound design, coupled with the more abstract visual of the empty hospital bed, helped us communicate in a more artful way.

In our first interview, you talked about learning storytelling structures in a playwriting class in college. Now that you’re in a different part of your journey, how do you continue the learning process to improve your craft?

I’m very much in the narrative world right now. I write my own projects. I’ve never waited for permission or for someone to invite me to the table and I won’t start now. I’ll always be working on my own material, in both film and television, and in the meantime, directing more on the episodic side. I relish the time when I can write and have creative control over the stories that I want to put out into the world. I watch a lot of films, read books, and study photographers and visual artists. I’m hoping to travel more this year with Hala on the festival circuit. I love reading director commentaries for research and inspiration. Most of my friends are filmmakers themselves, and I learn so much from them everyday. And when I feel uninspired, I take a beat and do something entirely different. I want to fill my life with experience. It’s an underrated and crucial part of the process; it’s not just working to work, but also living to have something to say.

"One morning, I woke up abruptly and told my partner that I had 'only 30 more years' to make movies and that I felt like I was running out of time."

What’s something you’ve seen recently that has moved you, asked a different question of you, or changed your perspective as a filmmaker?

I’ve been moved so much by television this year. Fleabag is a heartbreaking, staggering work of art; there is nothing like it. I started to question my own place in life and how I’m spending my time. I’m almost thirty. One morning, I woke up abruptly and told my partner that I had “only thirty more years” to make movies and that I felt like I was running out of time. I have so much anxiety about the future and what it will bring. Fleabag captured that anxiety perfectly.

I’ve also watched Barry. It’s so painful and funny and Bill Hader is such a talent, in front of and behind the camera. What does it mean to be an honest artist? What is the cost? Barry explores that. This past Sundance, I loved Lulu Wang’s The Farewell. It’s an incredibly moving story about a young woman who is wrestling with the truth about her grandmother’s terminal illness and whether to tell her, because keeping that news secret is a Chinese custom. It wrecked and inspired me. I wanted to call my mother. I wanted to call my family. I want to be more honest with them.

How has your experience with commercial projects influenced your approach to developing your own projects?

It’s the other way around. I’ve always known how I want to develop my own projects. My narrative experience has shaped how I want to work in commercials. I only want to work on projects that I feel uniquely suited to bringing to life. I want to have some semblance of creative control; the clients have to have some sort of trust in what I bring to the table.

Having worked on the PSA, I have a better sense of what it’s like to work on projects on a larger scale, what it means to collaborate with clients and deliver a project that is not purely an artistic endeavor. I was lucky to start in the commercial world on a project about a cause that I care about so much. I’m not one of those directors that is excited to run out and shoot just to shoot. There is a lot of visual noise out there. I have to have something to say. One aspect has changed, however. For this next feature, I’m doing research and interviews. I’m taking the process slowly. I want to listen first, then make.